American Street Kid, Celeste Farmer, Courtney Reid, Dave Johnson, documentaries, homeless, Ishmael Herring, Los Angeles, Marquesha Babers, Michael Leoni, Michelle Kaufer, movies, Nicholas Pumroy, reviews, Ryanne Plaisance

August 31, 2020

by Carla Hay

Directed by Michael Leoni

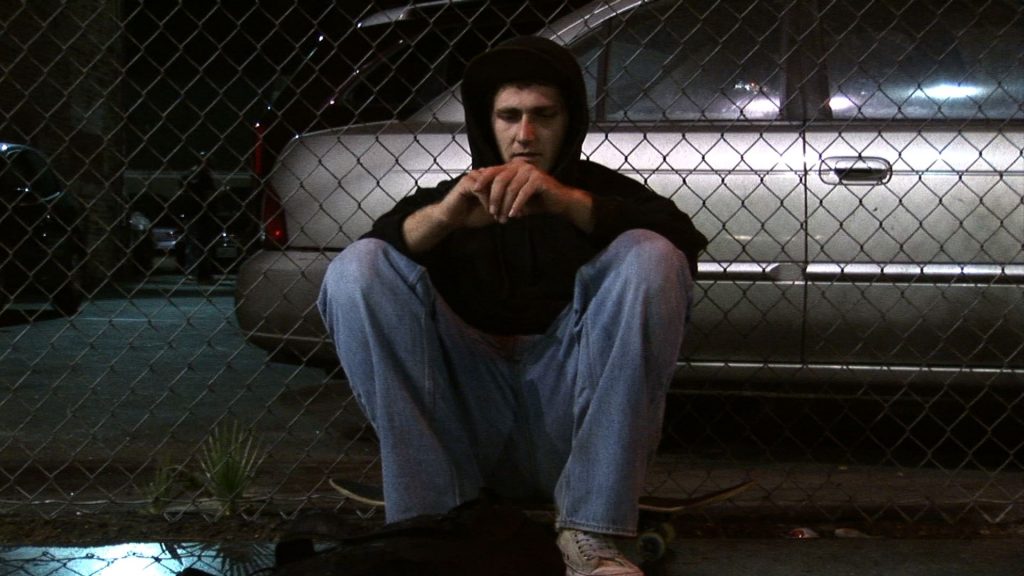

Culture Representation: Taking place in Los Angeles, the documentary “American Street Kid” features a predominately white group of people (with a some African Americans and Latinos) experiencing or discussing the problems of homeless youth.

Culture Clash: Young people who are homeless usually come from abusive backgrounds and have turned to drugs and/or crime while living on the streets.

Culture Audience: “American Street Kid” will appeal mostly to people who are interested in a gritty saga of homeless youth that is disturbing in showing what they’ve experienced but also inspiring in showing how some have managed to turn their lives around.

The traditional school of thought in documentary filmmaking is that the filmmakers shouldn’t get personally involved with their subjects, because it will alter or manipulate the outcome of the documentary. Michael Leoni, the writer/director of the documentary “American Street Kid” didn’t follow that tradition. And when people see “American Street Kid,” it’s easy to see why.

The movie takes a harrowing, emotionally chaotic and sometimes uplifting journey as Leoni chronicled the lives of several homeless youth he met on the streets of Los Angeles over a period of about five years. As seen in the documentary, Leoni ended up helping several of the young people he met while filming the documentary, even to the point of paying for many of them to stay in hotels until he ran out of money to do that. He also invited a few of them to temporarily live with him. “American Street Kid” started making the rounds at film festivals in 2017, years before the movie’s 2020 release, but the problems documented in “American Street Kid” still exist for millions of homeless people.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, as of 2019, there were an estimated 4.2 million youth and young adults experiencing homelessness in the United States every year. “American Street Kid” repeatedly mentions that 1.8 million young people in the U.S. are homeless (without giving a source for that statistic), but it’s unknown how outdated that statistic is in relation to the year that this documentary was released. It’s also possible that some statistics about homeless youth have different criteria of what the maximum age is to be considered a “young adult.”

In “American Street Kid,” which is narrated by Leoni, he explains that his interest in filming and ultimately helping homeless youth started when he met a young homeless woman named Seana, who frequently attended “The Playground,” a Los Angeles play about homeless kids that Leoni wrote and directed. In archival footage, Seana is seen briefly in the beginning of the movie, talking about how she used to live in foster homes and she became homeless when she was a teen runaway. Seana also said that her hope was to be clean and sober for 10 years before she dies.

Seana introduced Leoni to a 16-year-old homeless girl named Raven, who also became a fan of “The Playground.” Leoni says that Raven really connected to a character in “The Playground” who was a 16-year-old prostitute, because Raven was experiencing the same things. In “The Playground,” this character was murdered and dumped in an alley. Tragically, the same thing happened to Raven. It’s also revealed in the beginning of the movie that Seana died too.

These tragic deaths motivated Leoni to reach out to Stacia Fiore, who was head of outreach for Stand Up for Kids, a non-profit group for homeless youth. Leoni volunteered to make a two-minute public service announcement to give awareness about the plight of homeless youth in the Los Angeles area. The idea was that the PSA could help organizations such as Stand Up for Kids to help these homeless people. Phone calls between Leoni and Fiore are shown throughout the documentary.

What started out as making a two-minute PSA turned out to be a years-long journey into making this documentary film, as Leoni got more and more involved in helping and advocating for homeless youth. He began filming in Venice and Hollywood, two Los Angeles neighborhoods that have large populations of homeless people. And he explains in a voiceover that it took a while for the homeless people to trust him, but eventually many of them did. In the documentary, Leoni opens up to them about his own troubled background with drugs and temporary homelessness, which makes a difference in how he’s able to relate to the people he’s filming.

“American Street Kid” focuses on the stories of nine of these homeless youth, whose ages ranged from 15 to mid-20s at the time they were filmed for this documentary. Most of them do not have their full names revealed in the movie, and they usually have street nicknames. The young people who are spotlighted in “American Street Kid” are:

- Bublez (pronounced “bubbles”), originally from Washington state, a teen runaway who says she left home because of her mother’s abusive boyfriends and because she was depressed and suicidal after a friend of hers got shot.

- Dave “Greenz” Johnson (he’s nicknamed Greenz because of his love of marijuana), originally from Arizona, whose mother kicked him out of their home and who says that his meth-addict father has been in and out of prison for drugs.

- Nicholas “Nick” Pumroy, originally from Mississippi, who is Johnson’s best friend on the streets and who says he came from a family of abusive drug addicts.

- Ishamel “Ish” Herring, originally from Kansas, is an orphaned aspiring singer/musician who says his mother was a prostitute and his father was a pimp.

- Marquesa “Kiki” Babers, originally from North Carolina, who says she was raped at 9 years old by her mother’s boyfriend and who is practically inseparable from her best friend Akira, who is also a homeless teen.

- Ryan, originally from Arizona, who describes growing up in a household where his mother and stepfather used meth and his stepfather abused him.

- Vanessa (also known as Nessa), a California native who is Ryan’s girlfriend and who is HIV-positive and pregnant with Ryan’s child,

- Crystal, originally from Florida, who’s also pregnant and who says her meth-addict father named her after crystal meth and her grandmother often physically abused her.

- Mischa, originally from Massachusetts, who says she grew up in abusive households where she was beaten and raped.

In telling their stories, the homeless people in the documentary have several things in common: They became homeless not through choice but through circumstances, because they came from abusive backgrounds and the homes they had before were unbearable. Many were in foster care before they turned 18 years old. Childhood abuse (physical, sexual, emotional) is also a common trait of homeless people. The homeless people in the documentary all say that they were abused by family members and/or people in foster care.

And almost all of the homeless youth in the documentary have drug problems, which they usually had before they became homeless, but their drug addiction/abuse became even more of a way of life after they became homeless. In some scenes, Bublez, Nick, Greenz, Mischa, Ryan and Nessa are shown admitting on camera that they’re under the influence of drugs at the time of filming the scene.

Meth is mentioned the most as the drug that the homeless youth are abusing in this documentary (which includes a few scenes of people using drugs), but other drugs are mentioned too, including cocaine, heroin, barbiturates, marijuana and alcohol. The documentary also mentions that meth is popular with homeless people because they often have to spend a lot of time trying to get money and the meth is a way for them to stay awake longer.

The drugs are used to try to block out painful memories of abuse and also as a way to deal with the stress and shame of being homeless. But spiraling into addiction causes a whole new set of problems that aren’t experienced by drug addicts who are not homeless. A homeless drug addict who gets arrested almost never has the money to afford an attorney and rehab. And when they are let out of jail, they usually end up right back to living on the streets and doing the same things that got them arrested, causing a vicious cycle.

The documentary also mentions problems that are well-known to people who know about the plight of the homeless: It’s hard to get a job without an ID or an address. Having identification is a big issue for the homeless people who don’t have access to their birth certificates. Many of them don’t know how to get a copy of their birth certificate and Social Security number (if they are U.S. citizens), which they would need to get a job.

Fiore comments in the documentary: “It’s very, very unlikely that the [homeless] children have chosen to live on the streets.” And for kids under the age of 18, the foster care system can be a nightmare. Mischa, who says she was in foster care from the ages of 10 to 18, makes this chilling statement in the documentary: “I’d rather be beaten and raped every day than have been in the foster care system. They don’t give a fuck about you. You’re just a number.”

Ish says that people who aren’t homeless often have the wrong ideas about homeless people: “The common misconception is that we don’t want to work, that we’re lazy, or that we’re leeching off the system, or that we willfully choose to suffer. To me, that’s sad, because they don’t understand how much work and how much hustling goes into survival.”

Because they don’t have a permanent address and they often don’t have any ID, homeless people get their money any way that they can. Asking for money on the streets is one way. “Spange” is the street term for asking for spare change. The movie shows that some of the homeless youth are so desperate for money that they have signs that say things like “Kick Me in the Ass for $1,” and passersby actually pay to kick these homeless people. Bublez is one of the homeless people in the documentary that uses this tactic to get money.

Crime is another way that unemployed homeless people get money. Stealing, selling drugs and prostitution are the most common crimes committed by homeless people. “American Street Kid” doesn’t show any of the featured homeless people stealing or selling drugs, but Nick and Mischa openly admit that they prostitute themselves for money, and they are shown approaching potential customers for prostitution work.

“American Street Kid” has the expected scenes of the homeless on the streets and squatting in filthy, abandoned houses in crime-ridden areas. Sleeping in certain areas can make people vulnerable to being attacked, which is another reason why a lot of homeless people are reluctant to go to sleep, which is in turn linked to drug problems. And some of the people featured in the documentary sometimes go missing, usually because they’re on a drug binge.

But the movie never loses sight of the possibility that homeless people can go missing for more ominous reasons: They might have been murdered. (During the course of the movie, one of Ish’s former acquaintances was found dead, with blunt force trauma to the back of his head.) It’s also implied in the movie that homeless females are vulnerable to being kidnapped and forced into sex trafficking.

There are also incidents where the homeless people in the documentary get robbed or assaulted, which don’t happen on camera but are described after Leoni gets frantic phone calls from them and he rushes to their aid. The homeless people are reluctant to call police in these incidents because they don’t want to be arrested for vagrancy. And homeless kids who are underage don’t want to be put in the foster care system or be forced to go back to their abusive homes. Leoni assures them that he will never betray their trust.

Over time, it’s clear that the bond between Leoni and many of the homeless people got so deep and personal that they became like family to each other. Leoni could no longer stand by as an objective filmmaker, and he did everything he could to help them. There are several scenes in the movie with Leoni trying to get the homeless people into shelters, transitional living facilities or in rehab. When he paid for them to stay in hotels, he frequently paid for their meals too.

The results are mixed, and the movie shows the highs and lows of Leoni’s experiences in trying to save the homeless people from their destructive and dangerous situations. It’s an uphill battle, as the ones who are drug-addicted have a hard time changing their self-destructive ways. Another big issue is that resources are limited for homeless people, because shelters, government agencies and non-profits that are supposed to help the homeless are usually under-funded and under-staffed. And a major problem with homeless shelters is that they are often more dangerous than living conditions on the streets, as it’s pointed out in the documentary.

Fiore warns Leoni several times not to get too close to the homeless people he’s filming because he will end up getting disappointed and emotionally hurt. Leoni’s producing partner Michelle Kaufer (who is not seen in the documentary but can be heard in phone conversations) also expresses major concerns about the extent that Leoni is getting personally involved with the homeless people being filmed for the documentary.

The movie shows how Leoni’s relationships evolved with several people, particularly with Nick, Greenz and Ish, who all are invited to live temporarily live with Leoni while they try to get their lives on track. At various times, Leoni also gives jobs to some of the guys. Ryan shows a passion for filmmaking, so Leoni hires him as a production assistant for the documentary. Leoni also hires Greenz and Nick to be part of the production staff of his play “Elevator,” despite objections from his producing partner Kaufer, who didn’t think it was a good idea for Leoni to hire them.

Of the homeless females in the documentary, Leoni is particularly fond of Bublez, whom he says he thinks of as his younger sister. He also goes above and beyond in getting involved with the pregnancies of Crystal and Nessa, by paying for some of their pre-natal care. Leoni also advises them to give their children up for adoption. Crystal is more willing than Nessa and Ryan to consider adoption. (The births of the children are included in the documentary.)

The documentary does an admirable job of showing that homeless people should not be reduced to their past and present problems but should be treated as individuals who deserve a chance to be happy and productive members of society. One of the questions that Leoni asks them throughout the film is what they wish they could be doing with their lives. It’s clear that someone even taking the time to ask this question makes an impact.

The answers to the questions vary. Ish (who sings, plays guitar and writes songs) wants to be a professional musician. He’s very talented, and people watching this documentary might already know about his work with William Pilgrim and the All Grows Up, an independent R&B/rock band. Kiki says she dreams of having her own soul food restaurant. Mischa says she wants to work with autistic kids or kids with troubled backgrounds. Ryan says he wants to be a filmmaker. Nick is interested in working in holistic therapy, and it’s shown in the movie how he handles an opportunity to be enrolled in the National Holistic Institute.

Although the documentary is mostly done in a cinéma vérité style with Leoni and the homeless people, there are a few “talking heads” interviewed for the film. Common Ground Community Center’s outreach director Courtney Reid and mental health counselor Celeste Farmer are shown as overwhelmed by the work they have to do and admitting that the center isn’t able to keep up with the demand. They say that one-on-one attention is next to impossible for the homeless people who come to the center.

Ryanne Plaisance, a former development director of the non-profit Los Angeles Youth Network, comments: “If you’re just providing the food and just providing the shelter, it’s just enabling kids to stay on the street. People who are making the decisions and the paperwork aren’t always in touch with the realities of the situations that are affecting the kids. What looks good on paper doesn’t always look good or work well in the real world.”

Some people who haven’t seen “American Street Kid” might cynically think that Leoni did the movie to make himself look good. However, it’s clear from how this movie evolved that he didn’t intend to get so involved in trying to help the people he was filming. Yes, he made a lot of personal sacrifices and took a lot of risks, but the movie makes it clear that the homeless people who accepted his help were the ones with the bigger life obstacles.

One of the most important lessons that Leoni says he learned from the experience is that it’s not enough to give homeless people money or jobs. Homeless people, like anyone else, want to feel like they belong to a family. The homeless problem might never be solved, but “American Street Kid” has some valuable life lessons (some are harsh, some are inspirational) that show how one person can make a difference if they are willing to accept that not everyone will get a happy ending.

Kandoo Films released “American Street Kid” on digital and VOD on August 21, 2020.