Abiodun Oyewole, Alice LaBrie, Alvin Poussaint, Amiri Baraka, Anna Maria Horsford, Beth Ausbrooks, Billy Taylor, Carmen de Lavallade, Cheryl Sanders, Chester Higgins, Christopher Lukas, David Leeming, David Peck, Ellis Haizlip, Felipe Luciano, George Faison, Greg Tate, Harold C. Haizlip, Harry Belafonte, Hugh Price, Judith Jamison, Kathleen Cleaver, LGBTQ, Loretta Long, Louis Massiah, Mary Wilburn, Melba Moore, Melissa Haizlip, movies, Mr. Soul!, music, National Education Television, Nick Ashford, Nikki Giovanni, Novella Nelson, Obba Babatunde, Questlove, reviews, Robert Thompson, Sade Lythcott, Sarah Lewis, Sonia Sanchez, Stan Lathan, Sylvia Waters, The Last Poets, Thomas Allen Harris, TV, Umar Bin Hassan, Valerie Simpson

September 17, 2020

by Carla Hay

Directed by Melissa Haizlip

Culture Representation: The documentary film “Mr. Soul!” examines the history of Ellis Haizlip, the co-creator/host of the National Education Television (NET)/PBS variety series “Soul!” (which was on the air from 1968 to 1973), and interviews a group of African Americans and white people who are entertainers, current and former TV producers, artists, educators, authors and civil rights activists.

Culture Clash: “Soul!” was the first nationally televised U.S. variety series that gave a spotlight to African American culture, and a lot of the show’s content was considered edgy and controversial.

Culture Audience: “Mr. Soul!” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in African American culture or TV shows from the late 1960s and early 1970s.

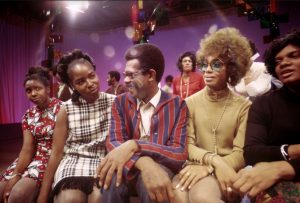

Before there was BET, before there was “Soul Train,” a publicly funded variety series called “Soul!” paved the way for nationally televised U.S. programming devoted to showcasing African American culture. “Soul!” was on the air from 1968 to 1973, but the excellent documentary “Mr. Soul!” tells the inside story of how “Soul!” co-creator/host Ellis Haizlip (who died in 1991, at the age of 61) had the vision to mastermind this type of programming, which was revolutionary at the time and continues to influence African American entertainment variety shows today.

Ellis Haizlip’s niece Melissa Haizlip skillfully directed this documentary, which has a treasure trove of archival footage and insightful commentary from a diverse array of people who were connected to the show in some way. Some of the documentary includes Ellis’ own correspondence, which is narrated in voiceover by actor Blair Underwood.

In watching the documentary, it’s clear that “Soul!” was definitely a product of its time. The show was conceived and born during the turbulent civil rights era of the late 1960s, when the U.S. was reeling from the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy in 1968, after John F. Kennedy and Malcolm X were also murdered earlier in the decade. The Black Power movement was a force to be reckoned with , and so it was only a matter of time before TV executives decided there was a need to give the movement a showcase on television.

As the documentary points out, although Ellis Haizlip was one of the co-creators of “Soul!,” he didn’t initially plan to be the on-camera star of the show, since he preferred to work behind the scenes. According to “Soul!” co-creator/producer Christopher Lukas, he and Ellis decided to start the show after Lukas kept hearing Ellis talk about “how lively the renaissance of the arts of black communities around the country” was and there should be a TV show it.

Dr. Harold C. Haizlip, a cousin of Ellis and a short-lived host of “Soul!,” confirms that Ellis’ vision was to “legitimate all of the variety of expressions of the arts,” particularly in the African American community. Nat King Cole and Harry Belafonte (who is interviewed in “Mr. Soul!”) had their own variety/talk shows, but those programs were aimed mainly at white audiences. Lukas says that Ellis didn’t want “Soul!” to be an African American version of “The Tonight Show,” but wanted “Soul!” to be “deeper, jazzier and more controversial” than the typical variety show on national television.

Of course, a TV show with this type of content can’t be at the mercy of advertisers, so public television was the best fit for “Soul!,” at a time when cable TV and the Internet didn’t exist. According to Lukas, the Ford Foundation quickly stepped up to fund “Soul!” as a New York City-based TV series on the nonprofit NET network, which was part of PBS. Lukas remembers that the title of “Soul!” was admittedly generic, but it was the only title that the producers could agree upon that best encompassed the spirit of the show.

Although there were other African American shows on U.S. public television that came before “Soul!” (such as “Black Journal,” “Like It Is,” and “Say Brother,” now titled “Basic Black”) these were primarily news and public-affairs programs. “Soul!” aimed to have to have more of a focus on arts and entertainment, while also including commentary about news, politics and other social issues, as they pertained to African Americans.

Dr. Alvin Poussaint, a world-renowned Harvard University professor and psychiatrist whose specialty is African American studies, was chosen as the first host of “Soul!” But his prestigious academic background didn’t translate well to him being a great TV personality, according to Poussaint and other people in the documentary. And so, Poussaint was asked to leave the show after only four episodes, according to Lukas.

The next host of “Soul!” was Harold Haizlip, who admits he wasn’t well-suited to be the show’s host either. At the time, he had a day job as headmaster for New Lincoln School, a New York City private school for kids in pre-kindergarten through 12th grade. Harold says that hosting “Soul!” was considered “radical” at the time, so he was slightly afraid that people from his highbrow academic world would find out and ostracize him. Harold didn’t have to worry about that for long, since he also parted ways with the show.

Lukas remembers that Ellis was initially reluctant to host “Soul!” because Ellis didn’t have a lot of on-camera experience. However, Ellis was eventually convinced to host “Soul!” when he figured out that, as the “face” of “Soul!,” it would give him more power to fulfill his vision for the show. Ellis started out as a very awkward host, but he eventually got the hang of it. And because Ellis did not have a highly academic persona, like the predecessor hosts, he probably came across as more “relatable” to the audience.

Several people, including Harold Haizlip and Lukas, mention that because Ellis was an openly gay man who knew what it was like to experience bigotry, that probably affected his willingness to be more open-minded to have guests on the show who were rejected by other TV shows. It’s noted many times in the documentary that if Ellis really liked a new artist, it didn’t matter if the artist had a hit or not, he wanted to champion the artist on the show. Several people mention that, unlike other TV programs that had lip syncing from music performers, “Soul!” always required that people perform live, giving the show a level of authenticity that other variety shows did not have.

Ashford & Simpson, Patti LaBelle and the Bluebells, Al Green, Toni Morrison, Arsenio Hall Roberta Flack, Novella Nelson and Earth Wind & Fire were among the artists who got their first major TV breaks by appearing on “Soul!” In the documentary, Valerie Simpson says, “There would not be an Ashford & Simpson without ‘Soul!'” Simpson’s husband/musical partner Nicholas “Nick” Ashford says that Ellis believed in them before they believed in themselves. (Ashford was interviewed for the movie four months before he died in August 2011, according the documentary’s production notes.)

Ellis also didn’t limit his choices to artists who did “safe” material, since many of the guests were controversial. Lukas says that Ellis wanted to embrace the radicals and the religious conservatives in the African American community. Louis Farrakhan, who would become the leader of the Nation of Islam in 1977, was a guest on “Soul!” in 1971. Farrakhan, who is considered the leader of Black Muslims in America, has frequently come under fire for comments that are anti-Semitic, racist against white people and homophobic. It’s noted in the documentary that Ellis’ “Soul!” interview with Farrakhan was the first time that Farrakhan admitted on TV that he would try to be more open-minded when it came to accepting people who aren’t heterosexual.

The Last Poets, an all-African American male poetry group, was on “Soul!” multiple times. The group was controversial for frequently using the “n” word in its poetry lines and titles. When the Last Poets would perform on “Soul!,” it was completely uncensored, as it is in this documentary. Last Poets members Abiodun Oyewole and Umar Bin Hassan are among the documentary’s interviewees. Oyewole comments on the group’s frequent use of the “n” word in its art: “You’ve got to show how black you are by your actions.”

“Soul!” was not only very Afro-centric on camera, but the show was also very Afro-centric behind the scenes, since the majority of the show’s producers were African American women, according to the documentary. Former “Soul!” associate producers Anna Maria Horsford and Alice LaBrie are among those interviewed in the documentary. “Soul!” gave a great deal of airtime to black women co-hosting the show and doing on-camera interviews, when nationally televised U.S. primetime variety series, then and now, usually hire white men for these jobs.

In one episode, “Soul!” devoted the entire episode to African American female poets. “Soul!” also gave a big platform to activist/poet Nikki Giovanni, who appeared on the show numerous times and is interviewed in the documentary. Her 1971 exclusive interview with writer James Baldwin is considered one of the highlights of “Soul!’s” history. (Ellis and Baldwin initially didn’t along with each other, but the two men would eventually work together on “The Amen Corner” tour of the stage play.)

Loretta Long, who was an original “Soul!” co-host, remembers that the show gave her an opportunity to be on television at a time when television was limiting casting of African American women to mostly subservient or demeaning roles. Long says in the documentary about her on-camera opportunities at the time: “Television wasn’t an option for me, because I didn’t want to be Beulah. I didn’t want to be the maid.” She says of her first time on “Soul!”: “That first show, the atmosphere was electric!” Long would later go on to become one of the original stars of “Sesame Street.”

And long before Horsford found fame as an actress on sitcoms such as “Amen” and “The Wayans Bros.,” this former “Soul!” associate producer made several on-camera appearances on “Soul!” as an activist/poet. On a side note, the documentary includes late 1960s footage of actress Roxie Roker (Lenny Kravitz’s mother, who was most famous for co-starring on “The Jeffersons”) hosting the public-affairs/news program “Inside Bed-Stuy” It’s an example of the on-camera opportunities that public TV programs gave to African American women who were often shut out of other TV programs at the time.

Several people comment in the documentary that when African American guests came on “Soul!” (whose studio audience was also mostly African American), they showed a certain level of comfort that they didn’t have on other shows. When Grammy-winning legend Steve Wonder appeared on “Soul!” in 1972 to introduce his band Wonderlove, he didn’t seem to want to leave the stage. What was supposed to be a guest segment turned into an entire episode of Wonder performing.

Avant-garde jazz artist Rahsaan Roland Kirk was nowhere near as famous as Wonder, but he’s named in the documentary as an example of the type of “underground” African American artist who would never be able to get booked on any nationally televised primetime variety series at the time. The documentary includes footage of Kirk’s notorious 1972 appearance when he played three instruments at one time and ended the performance by ripping up a bridge chair on stage.

“Soul!” would later eventually expand its programming to include Latino issues and culture. Former “Soul!” host Felipe Luciano gets tearful in the documentary when he remembers how Ellis gave him his first opportunity to be a producer on the show. Luciano says that because of Ellis’ openness to include Latino culture in “Soul!,” Luciano was able to book and introducer Tito Puente on the show.

Some other notable appearances on “Soul!” included Sidney Poitier and Belafonte doing an interview together; Muhammad Ali discussing his conscientious objection to the Vietnam War; husband-and-wife actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee in one of their first TV appearances together; and interviews with activists Betty Shabazz, Stokely Carmichael and Kathleen Cleaver, who is interviewed in the documentary.

The documentary includes some family background information about Ellis (who grew up in the Washington, D.C., area), including mentioning that from an early age, he liked to direct performances and come up with creative ideas for shows. Ellis was the second child of four kids. He had an older sister named Doris, a younger sister named Marie and a younger brother named Lionel. Ellis was closest to Marie.

The family experienced a tragedy when Ellis’ beloved mother Sarah died when he was 17. His aunt Nellie than became like a surrogate mother to the kids. But Ellis’ father (Ellis Sr.), who’s described as very strict and religious, had a hard time accepting that Ellis was gay. Ellis’ cousin Harold gets emotional when he comments in the documentary about Ellis Sr.’s homophobia toward Ellis Jr.: “Even then, I knew Ellis was a very special person, and he needed a nourishing environment, rather than a critical one.”

Fortunately, Ellis found acceptance with his TV family at “Soul!” Before landing at “Soul!,” Ellis (a Howard University graduate) worked in theater while he was in college and eventually started working in television. “Soul!” came to an end when funding was cut off due to much of the controversial content.

As Harold comments about the show’s cancellation: “‘Soul!” was undiluted and absolutely in your face—and that was its value and also its undoing.” Former “Soul!” producer Luciano remembers being upset that Ellis was so calm and accepting about the cancellation, because he thought that Ellis would be more inclined to fight to keep the show on the air. A few days before the last episode of “Soul!” was filmed, another tragedy struck the Haizlip family. That tragedy won’t be revealed in this review, but it’s enough to say that it had a profound effect on Ellis, who continued to work for PBS for most of his career.

Other people interviewed in the documentary include Beth Ausbrooks and Mary Wilburn, two of Ellis’ childhood friends; actors Obba Babatunde and the late Novella Nelson; filmmakers Thomas Allen Harris, Louis Massiah and David Peck; writers Khephra Burns and Greg Tate; former “Soul!” production secretary Leslie Demus; former “Soul!” staff photographer Chester Higgins; dancers Carmen de Lavallade, , Sylvia Waters and Judith Jamison; choreographer George Faison; musicians Billy Taylor and Questlove; and activists Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez.

Also contributing their commentary are producer/director Stan Lathan; former National Black Theatre director Sade Lythcott; entertainer Melba Moore; former WNET executive/former National Urban League president Hugh Price, Rev. Cheryl Sanders, a niece of Ellis Haizlip; Syracuse University professor Robert Thompson; Harvard University professor Sarah Lewis; George Washington University professor Gayle Wald, author of “It’s Been Beautiful: Soul! and Black Power TV”; and “James Baldwin: A Biography” author David Leeming.

A lot of people who watch “Mr. Soul!” will find out many things about African American television that they didn’t know about before seeing this documentary. It’s why “Soul!” remains underrated and often overlooked when people talk about groundbreaking American television. But “Mr. Soul!” is a fitting and well-deserved tribute to “Soul!” and the visionary Ellis Haizlip, who took bold risks in bringing the show to life.

Shoes in the Bed Productions released “Mr. Soul!” in select U.S. cinemas on August 28, 2020.