Al Sharpton, Amir Hawkins, Christopher Graham, Conrad Tillard, Darlene Brown, David Dinkins, Diane Hawkins, documentaries, Douglas Nadjari, HBO, Herbert Daughtry, Joe Fama, John DeSantis, Ken Sunshine, Lenora Fulani, Luther Sylvester, movies, racism, reviews, Stephen Murphy, true crime, TV, Yusuf Hawkins, Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn

August 14, 2020

by Carla Hay

“Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn”

Directed by Muta’Ali

Culture Representation: Taking place in New York City, the documentary “Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn” features a predominantly African American group of people (and some white people) discussing the 1989 racist murder of 16-year-old Yusuf Hawkins and the controversial aftermath of this hate crime.

Culture Clash: Yusuf Hawkins was murdered by a mob of young white men just because Hawkins was an African American, and there were many conflicts over who should be punished and how they should be punished.

Culture Audience: “Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn” will appeal primarily to people interested in true crime stories that include social justice issues.

The insightful documentary “Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn” gives an emotionally painful but necessary examination of the impact of the 1989 murder of Yusuf Hawkins, a 16-year-old African American who was shot to death in New York City’s predominantly white Brooklyn neighborhood of Bensonhurst. He was killed simply because of the color of his skin—and it’s a tragedy that has been happening for centuries and keeps happening to many people who are victims of racist hate crimes. This documentary, which is skillfully directed by Muta’Ali, offers a variety of perspectives in piecing together what went wrong and what lessons can be learned to help prevent more of these tragedies from happening.

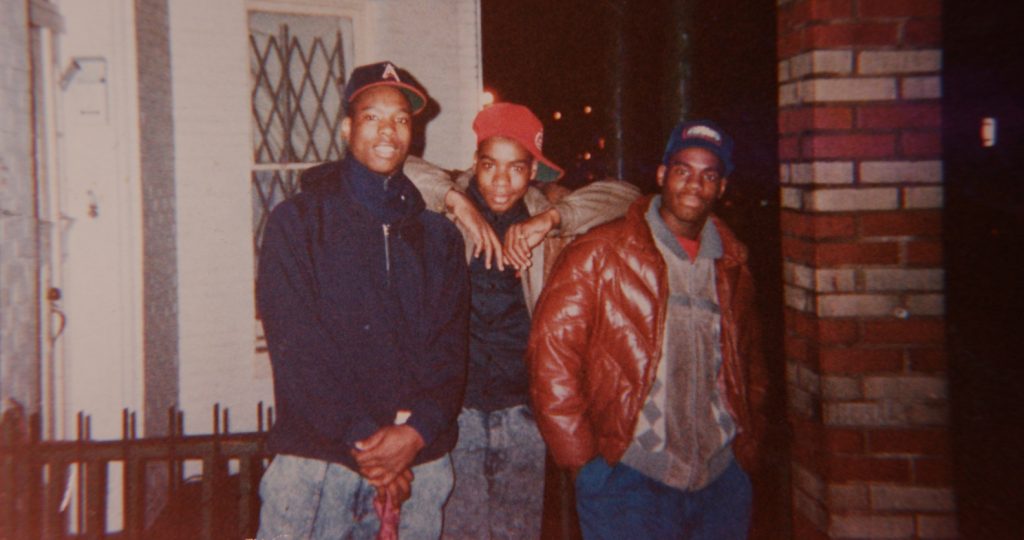

One of the best aspects of “Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn” is how it has interviews with many of the crucial people who were directly involved in the murder case and the subsequent controversy over how the perpetrators were going to be punished. The people interviewed include members of Yusuf Hawkins’ inner circle, such as Yusuf’s mother, Diane Hawkins; his younger brother Amir and older brother Freddy; Yusif’s cousins Darlene Brown and Felicia Brown; and Yusuf’s friends Christopher Graham and Luther Sylvester, who was with Yusuf during the attack. (Yusuf’s father, Moses Stewart, died in 2003.) They are all from the Brooklyn neighborhood of East New York.

The documentary also has the perspectives of some Bensonhurst residents or people who allied themselves with the accused perpetrators. They include Joe Fama, who was convicted of being the shooter; Stephen Murphy, who was the attorney of Keith Mondello, who was accused of being the mob’s ringleader; and Russell Gibbons, an African American who was a friend of many of the white men in the mob of attackers. Gibbons was involved in providing the baseball bats used in the attack, but Gibbons ended up testifying for the prosecution.

And in the aftermath of the murder, several people became involved in the investigation, court cases and public outcry seeking justice for Yusuf. The documentary includes interviews with activists Rev. Al Sharpton, Dr. Lenora Fulani, Rev. Conrad Tillard (formerly known as Conrad Muhammad) and Rev. Herbert Daughtry; Douglas Nadjari, who was New York’s assistant district attorney at the time; former New York City mayor David Dinkins; publicist Ken Sunshine, who was Dinkins’ deputy campaign manager at the time; Joseph Regina, a New York Police Department detective involved in the investigation; and journalist John DeSantis, who covered the Yusuf Hawkins story for United Press International.

There have been many disagreements over who was guilty and who was not guilty over the physical attacks and shooting, but no one disputes these facts: On August 23, 1989, Yusuf and three of his friends—Luther Sylvester, Claude Stanford and Troy Banner (who are all African American)—went to Bensonhurst at night to look at a 1987 Pontiac Firebird that was advertised in the newspaper as being for sale. Banner was the one who was interested in the car.

When they got to Bensonhurst, all four of them were surrounded by a mob of young white men who were in their late teens and early 20s (it’s estimated that 10 to 30 people were in this mob), who attacked them with baseball bats and yelled racial slurs at them. Yusuf was shot to death during this assault. (A handgun was used in the shooting.) The attack was unprovoked, and several people involved in the attack later admitted that it was a hate crime.

Nadjari comments in the documentary: “Yusuf and his friends walked into what I call ‘the perfect storm’ … They [the attackers] didn’t want black guys in the neighborhood.” And even defense attorney Murphy admits: “You’d have to be stupid to not determine that there was a racist element to the whole thing to begin with.”

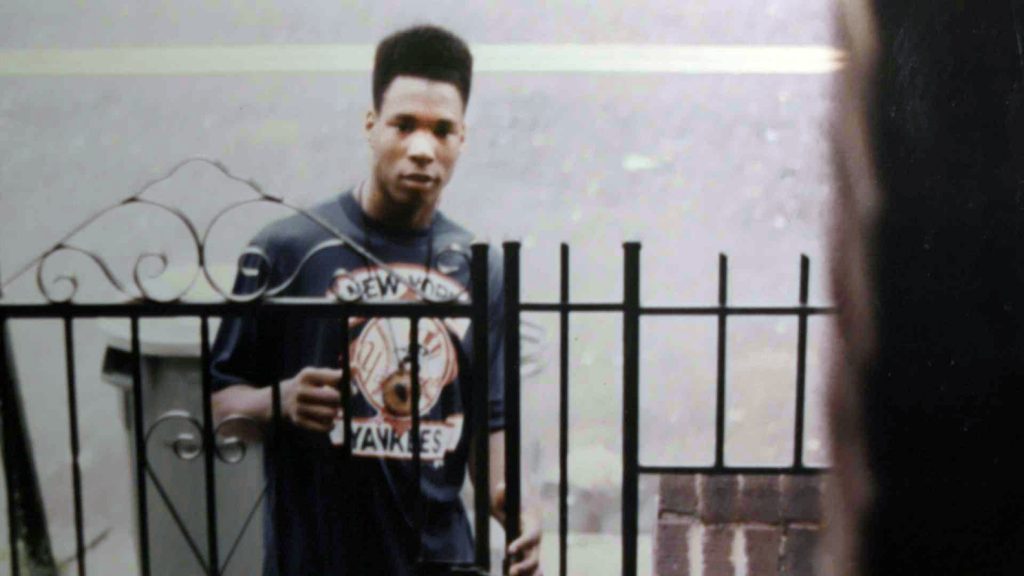

Furthermore, Yusuf and his friends were not “thugs” with a history of violence. All of the people who knew Yusuf describe him as a thoughtful, caring and good kid. He was the type of person who looked out for his friends to steer them away from trouble. It was consistent with his personality that he would accompany a friend who wanted to look at a car for sale. As journalist DeSantis comments in the documentary about Yusuf: “He was perceived by many to be a martyr.”

It came out during the investigation that a lovers’ quarrel was the spark that ignited the viciousness of the attack. Mondello’s girlfriend at the time was Gina Feliciano. During an argument between Feliciano and Mondello earlier that evening, she said that she was going to have a bunch of black guys come to the neighborhood to beat up Mondello and his friends. Feliciano lied in that threat, but apparently Mondello believed her. According to testimony in the trials, Mondello and the rest of the mob wrongly assumed that Yusuf and his friends were the (fabricated) gang of black thugs that Feliciano had said was coming to assault Mondello.

The documentary points out that even though New York City has an image of being “liberal” and “cosmopolitan,” the city is not immune from racism and racial segregation. East New York and Bensonhurst are just 13 miles apart, but these two very different Brooklyn neighborhoods might as well have been on other planet, because the people in these neighborhoods rarely mixed with each other. East New York has a predominantly working-class black population, while Bensonhurt’s population consists mainly of middle-class white people, many who are Italian American.

According to Amir Hawkins, who was 14 at the time his brother Yusuf was murdered, even though he lived in Brooklyn for years, all Amir knew about Bensonhurst was from “The Honeymooners,” one of his favorite sitcoms. He says of Bensonhurst: “Nobody told us, ‘Hey, that’s off-limits You can’t go there.'”

Amir also gives a chilling description of how his grandmother Rosalie seemed to have some kind of premonition that something would go horribly wrong when Yusuf was in Bensonhurst. According to Amir, when his grandmother found out that Yusuf had gone to Bensonhurst, Amir says he never saw his grandmother more upset in his life. Sadly, her apparent premonition turned out to come true, when the family got the devastating news about Yusuf’s murder later that night.

As an African American and longtime Bensonhurst resident, Gibbons admits in the documentary that he has experienced a profound racial identity crisis and still has deep-seated inner conflicts about race. He says that even though he was bullied by white racists in Bensonhurst, he also wanted to be friends with them. Gibbons was the only “black friend” of the mob accused of attacking Yusuf and his friends.

In the documentary, Gibbons downplays his role in providing the baseball bats used in the attack. Just as he said in trial testimony, Gibbons claims that all he heard on the night of the incident was that some black and Latino men were coming to Bensonhurst to attack some of his friends and he wanted to assist his friends in defending themselves. He says in the documentary, “I wasn’t thinking about race. I was just there because my friends were there.”

As for Fama, he says nothing new in the documentary that he hasn’t already claimed during his trial in 1990. Although he didn’t testify during his trial, Fama admits that he was part of the mob of attackers, but he claims that he’s not guilty of shooting Yusuf. Fama went into hiding after the murder, but he eventually turned himself in to police a little more than a week after the murder. During the documentary interview, Fama is shifty-eyed when discussing the case and seems more concerned about trying to appear innocent than expressing remorse about the circumstances that led to Yusuf’s murder.

Yusuf’s father (Moses Stewart) had been mostly an absentee father who left the family when Yusuf was about 17 months old. Walter Brown, a friend of Stewart’s, says in the documentary, says that Stewart was “stupid” for being a deadbeat dad, but Stewart wanted a chance to redeem himself. In January 1989, Stewart and Yusuf’s mother Diane reconciled, and so he was back in the family’s life. Seven months later, Yusuf was murdered.

After the murder, Stewart reached out to Sharpton who, along with other activists, spearheaded the protests and rallies demanding justice for Yusuf. Yusuf’s mother, father, brothers and other family members participated in many of these protests and rallies, but it’s mentioned in the documentary that Yusuf’s father was more comfortable than Yusuf’s mother with being in the media and public spotlight. There’s archival footage showing that Yusuf’s mother was often very reluctant to make a statement when there was a crowd of media gathered around asking her to say something.

In the documentary, Yusuf’s mother gives heartbreaking descriptions of her nightmarish grief. Its sounds like she had post-traumatic stress disorder, because she experienced panic attacks and became paranoid of going outside at night and was afraid of doing simple things such as taking the subway. She and other family members and friends confirm that losing Yusuf is a trauma that they will never get over.

Yusuf’s murder happened to occur in an election year for New York City’s mayor. The incumbent mayor Ed Koch was widely perceived by his critics as too sympathetic to the accused attackers. (Koch died in 2013.) Dinkins, who defeated Koch in the primary election and would go on to become New York City’s first black mayor, openly supported the Hawkins family before, during and after the trials took place. Dinkins comments in the documentary about how Yusuf’s murder affected the mayoral race that year: “I knew that Yusuf Hawkins would be a factor in my contest, but I’d like to believe that we treated it as we would have had I not been seeking public office.”

The protests also came at a time when filmmaker Spike Lee’s 1989 classic “Do the Right Thing” had entered the public consciousness as the first movie to make a bold statement about how racial tensions in contemporary New York City can boil over into racist violence against black people. It’s not a new problem or a problem that’s unique to any one city, but in the context of what happened to Yusuf Hawkins, “Do the Right Thing” held up a mirror to how these tragedies can occur. The documentary mentions that Lee and some other celebrities became outspoken supporters of the Hawkins family.

The documentary also offers contrasting viewpoints on the protests, which included protestors going into Bensonhurst on many occasions, sometimes to protest at other events happening in the neighborhood. There’s a lot of archival footage of the protestors (mostly black people) and angry Bensonhurst residents (mostly white men) clashing with each other, with many of the Bensonhurst residents and counterprotestors hurling racially charged and racist insults at the protestors.

While Sharpton and other activists involved with the protests felt that the protestors were peaceful and law-abiding, critics of the protests thought that the protestors were rude and disruptive. It’s part of a larger issue of how people react to racial injustice. Some people want to stay silent, while others want to speak out and do something about it.

In fact, it’s mentioned in the documentary that Yusuf’s family was initially told by police to not speak out about the murder because the police were afraid that news of the murder would cause civil unrest. But after the media reported that Yusuf’s murder was a racist hate crime, the crime couldn’t be kept under the radar. According to several people in the documentary, the media helped and hurt the case.

The documentary mentions that although the media played a major role in public awareness of this hate crime, the media (especially the tabloids) got some of the facts wrong, which distorted public opinion. One of the falsehoods spread by the media was that Yusuf or one of his friends in the attack was interested in dating white girls they knew in Bensonhurst, and that was one of the reasons for the attack. In fact, Yusuf and the three friends who were with him didn’t know anyone in Bensonhurst and were really there just to look at a car for sale.

And even though Dinkins publicly gave his support to the Hawkins family, the documentary reveals that there was tension behind the scenes between Dinkins and Sharpton. Dinkins wasn’t a fan of the protests because he felt that they were too disruptive, while Sharpton and many of his supporters thought that Dinkins and other local politicians weren’t doing enough to help with the protestors’ cause. The documentary shows that although Dinkins and Sharpton were at odds with one another over the Yusuf Hawkins protests, many people in positions of power (including Dinkins and Sharpton) used the murder case to further their careers.

Sharpton was also controversial because of his involvement in the Tawana Brawley fiasco. In 1987, Sharpton publicly supported Brawley (a teenager from Wappinger Falls, New York), who claimed that four white men had raped her and covered her in feces. But her story turned out to be a lie, and the hoax damaged Sharpton’s credibility, even though he claimed he had nothing to do with the hoax. Many of Sharpton’s critics pointed to the Brawley hoax as a reason why Sharpton couldn’t be trusted.

In the documentary, Fulani makes it clear that she thinks that it’s enabling racism when people are told to keep silent about it: “I think the problem is that the people who aren’t involved in being racist pigs couldn’t get it together enough to make a different kind of statement.” The documentary shows that a huge part of the controversy in cases such as this is that a lot people can’t really agree on what kind of statement or response should be made.

Gibbons, the African American who was a friend to the Bensonhurst mob of attackers, has this criticism of Sharpton and his protests: “Men like that, they do more damage, and maybe they think they’re doing good.” NYPD detective Regina adds, “Yusuf Hawkins did lose his life because the color of his skin, but not because Bensonhurst is a racist, vigilante neighborhood trying to keep colored people out … There was justice. And after that justice, there should have been peace.”

But considering the outcome of the trials, it’s highly debatable if justice was really served. And is there really peace when people are still getting murdered for the same reason why Yusuf Hawkins was murdered? As long as people have sharply divided opinions on how these matters should be handled by the public and by the criminal justice system, there will continue to be controversy and civil unrest.

“Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn” could have been a very one-sided documentary, but it took the responsible approach of including diverse viewpoints. “Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn” is the well-deserved first winning project of the inaugural Feature Documentary Initiative created by the American Black Film Festival and production company Lightbox, as part of their partnership to foster African American filmmakers and diversity in feature documentaries. And the poignant ending of this documentary makes it clear that Yusuf will be remembered for more than his senseless murder. The positive impact he made in his young life goes beyond what can be put in a news report or documentary.

HBO premiered “Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn” on August 12, 2020.