June 15, 2022

by Carla Hay

“The Lost Weekend: A Love Story”

Directed by Eve Brandstein, Richard Kaufman and Stuart Samuels

Culture Representation: The documentary film “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” features a nearly all-white group people (with one Asian) discussing the 1973-1975 love affair that John Lennon had with May Pang, who was also his personal assistant at the time.

Culture Clash: Pang, who is the documentary’s narrator, says that Lennon’s wife Yoko Ono insisted that Pang start an affair with Lennon during the spouses’ separation, and that Ono was the cause of manipulative conflicts that eventually led to Lennon reuniting with Ono.

Culture Audience: “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” will appeal mainly to fans of Lennon and the Beatles who want to know more about the life that Lennon had when he was separated from Ono.

In the very personal documentary “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story,” May Pang narrates and shares her memories of the love affair that she had with John Lennon from 1973 to 1975. Pang’s 1983 memoir “Loving John” went into many of the same details. However, this cinematic version of Pang’s story is a visual treat and an emotional journey that offers intriguing photos and audio recordings, including rare chronicles of Lennon’s reunions with his former Beatles bandmate Paul McCartney. “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” had its world premiere at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival in New York City.

Directed by Eve Brandstein, Richard Kaufman and Stuart Samuels (who are also the producers of the documentary), “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” refers to the notorious “Lost Weekend” in Lennon’s life. It actually wasn’t a weekend but it was in reality a period of about 18 months when Lennon was separated from his second wife, Yoko Ono, whom he married in 1969. It was also a time when, by Lennon’s own admission, he was drinking and drugging heavily, although Lennon says he eventually sobered up and stopped his hard-partying ways around the time he made his 1975 album “Rock and Roll.”

The documentary starts out with Pang describing her turbulent childhood where she often felt like a misfit. Born in New York City on October 24, 1950, Pang says that her Chinese immigrant parents had an unhappy marriage. She spent much of her childhood growing up in New York City’s Spanish Harlem area, which was populated by mostly African Americans and Puerto Ricans. “I was a minority among minorities,” Pang comments in the documentary.

Pang describes her father as “abusive” and someone who eventually abandoned her when he adopted a son, since her father was open about preferring to have a son. By contrast, Pang describes having a close relationship with her loving mother, who encouraged Pang to be strong and independent. Pang’s mother, who had “beauty and brains,” opened her own laundromat called OK Laundry. Pang’s older biological sister is not mentioned in the documentary.

Pang says, “Dad was an atheist, and Mom was a Buddhist, so naturally, they sent me to Catholic school … Dad fought with Mom. I fought with the nuns, so my only escape was music.” From an early age, Pang says, “I was hooked on rock and roll, especially these four guys from Liverpool.”

Those “four guys from Liverpool” in England were, of course, the Beatles. Pang didn’t like school very much, so she dropped out of college and quickly found a job working at the New York offices of ABKCO, the company that managed Apple Corps, the Beatles’ entertainment company. ABKCO, which was founded by Allen Klein, also managed Lennon’s solo career.

Pang says she walked in the office one day, asked if they were hiring, and she basically lied about having secretary skills in order to get the job. A week later, she started working for ABKCO’s Apple Corps side of the business. Pang describes herself as a go-getter who doesn’t get easily defeated.

But not long after she started working for Apple Corps, the Beatles announced their breakup in 1970. Pang then started to do more ABKCO work for the company’s management of Lennon’s solo career. By the early 1970s, Lennon and Ono had relocated to New York City as their primary home base, although they still maintained a home in England. And then, Pang was asked by Lennon and Ono to leave ABKCO to be the couple’s personal assistant. She eagerly accepted the offer.

Sometime in 1973, Lennon and Ono decided to separate. Ono had an unusual demand during this separation: According to Pang, Ono told Pang that Pang had to start an affair with Lennon. The reason? Ono knew that Lennon would be dating other women, and she felt that Pang was a “safe choice.” Pang and Lennon than moved to Los Angeles, where the so-called “Lost Weekend” really began. In the documentary’s archival interview footage (which is mostly from the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s), Ono is seen in a TV interview where she doesn’t really deny Pang’s claims, but Ono is vague about how she interacted with Lennon and Pang during the marital separation.

Just as Pang did in her memoir and in many interviews that she’s given over the years, Pang says in the documentary that she was at first very confused and frightened by Ono’s demand for Pang to have an affair with Lennon. Up until that point, Pang’s relationship with Lennon was strictly professional. Pang says her first instinct was to say no, but she eventually agreed because she says she didn’t want to lose her job. She also liked Lennon immensely as a person. Pang describes him as witty, funny, intelligent and generous, but with a bit of cruel streak and some insecurities that didn’t make him always easy to deal with on a daily basis.

Pang says that after Ono gave Lennon “permission” to start dating Pang, Lennon ended up pursuing Pang, starting with flirting. Flirting led to kissing, and then after a short period of time, they became lovers. Pang says, “Before I knew it, John Lennon charmed the pants off of me.” Pang remembers her first sexual encounter with Lennon: “After we made love, I started to cry.” She says she asked him: “What does this mean?” Lennon replied, “I don’t know.”

Pang says in the documentary that she believes Ono mistakenly assumed that Lennon and Pang would have a casual fling. Instead, Pang says that her romance with Lennon was true love for the both of them, and she and Lennon eventually moved in together. Before Lennon and Ono reunited in 1975, Pang says that Lennon and Pang looked at houses on New York’s Long Island, because he was planning to buy a Long Island home where they could live together.

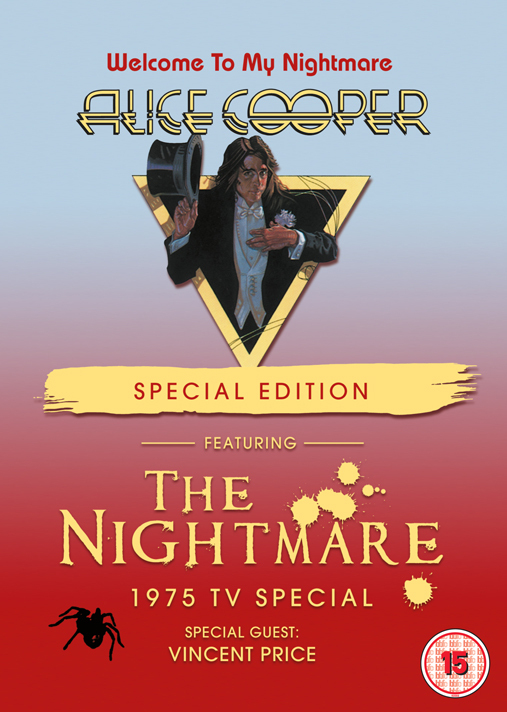

At the beginning of the relationship, Pang and Lennon spent most of their time in Los Angeles, where he did a lot of heavy partying with friends such Ringo Starr (his former Beatles bandmate), Harry Nilsson, Keith Moon, Alice Cooper, Micky Dolenz and former Apple Corps employee Tony King. Cooper said they called themselves the Hollywood Vampires. The documentary includes some amusing video footage of King, dressed in drag as Queen Elizabeth II, doing a commercial for Lennon’s 1973 “Mind Games” album, with Lennon and King goofing around with King’s ball gown lifted up to show his underwear.

The intoxicated partying wasn’t all fun and games. Pang retells the infamous stories about how much of a tyrant Phil Spector was as a music producer in the studio, especially when he was drunk, which was often during this period of time. Spector was a producer of the Beatles’ 1970 “Let It Be” album and several of Lennon’s solo albums. Pang was there to witness Spector taking out a gun and shooting during an argument in the studio. (It’s a well-known story.)

Luckily, no one was physically hurt during that incident. But considering that in 2009, Spector was convicted of the 2003 shooting murder of actress Lana Clarkson, it’s an example of how his dangerous and erratic behavior had been going on for years prior to the murder. (Spector was still a prisoner in California when he died of COVID-19 complications in 2021. He was 81.)

Eventually, Lennon befriended Elton John and David Bowie, which resulted in successful collaborations with these other music legends. Lennon provided background vocals for Bowie’s 1975 hit “Fame.” John provided harmony and played keyboards on Lennon’s 1974 hit “Whatever Gets You Thru the Night.” Pang retells the story of how she and Lennon were in bed watching televangelist Reverend Ike on TV, and the preacher said, “Whatever gets you through the night” as part of the sermon. It inspired Lennon to write the song.

Lennon and John performed “Whatever Gets You Thru the Night” live one time on stage at John’s Madison Square Garden concert on November 28, 1974, after Lennon lost a bet. When they were recording the song in the studio, John had predicted that the song would be a No. 1 hit in the United States. Lennon disagreed, so John made a bet with Lennon that if the song became a No. 1 hit, Lennon would have to perform the song in concert with John if that prediction turned out to be true.

This concert was Lennon’s first time performing at an arena show without the Plastic Ono Band (whose members included Ono), and it would turn out to be his last time performing in public. Pang describes Lennon as being extremely nervous before the performance. It was also at this fateful concert that Ono showed up backstage in what would be among the many signs that she was ready to get back together with Lennon.

Pang says in the documentary that some of her best memories of being with Lennon were the times she spent in the recording studio with him. She was credited as a production coordinator in several solo albums that Lennon made during the 1970s. Pang also did some backup vocals on a few of Lennon’s solo songs, most notably on “#9 Dream” from Lennon’s 1973 “Walls and Bridges” album. Pang can be heard whispering “John” on the song.

She got to witness a lot of music history, including a jam session with Lennon, McCartney and Stevie Wonder doing an impromptu version of Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me.” Pang says that Linda McCartney (Paul’s first wife) was playing the organ during this session, while Pang and Mal Evans (former Beatles road manager/personal assistant) accompanied on tambourine. The documentary includes a brief audio clip of this recording session, which is believed to be the last recording of Lennon and Paul McCartney playing music together.

Pang was an avid photographer who took a lot of photos during this period of time that she was involved with Lennon. Her photo book “Instamatic Karma: Photographs of John Lennon” was published in 2008. “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” also includes many photos from Pang’s personal collection.

Once such photo that Pang took of Lennon and Paul McCartney was at a hillside house in Los Angeles where Lennon was staying in 1974. (The house was semi-famous for being where Marilyn Monroe would have sexual trysts with John F. Kennedy and his younger brother Robert F. Kennedy.) The candid photo shows Lennon and Paul McCartney sitting outside (on what looks like a balcony) and talking while shielding the sun with their hands near their eyes. Pang says it’s the last-known photo of Lennon and Paul McCartney together.

“The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” also includes several of Lennon’s sketches and doodles that he gave to Pang as gifts. One of these drawings shown in the documentary is of the UFO sighting that Pang says she and Lennon experienced one night when they were on the top of their New York City apartment building on August 23, 1974. Another illustration shows what Lennon (who went to art school when he was in his teens) thought his future would look like. The drawing depicts him in a heavenly-type garden as a naked, potbellied old man with a young-looking and nude Pang floating above on a cloud.

Pang also credits Lennon with being the inspiration for her political awakening in the early 1970s. He was an outspoken anti-war activist, which got him on the “enemy of the state” radar of then-U.S. president Richard Nixon, whose administration caused immigration problems for Lennon. It was revealed years ago that Lennon was under FBI surveillance during this time. All of these issues are mentioned in the documentary through archival news footage. Pang doesn’t give any further insight, except to say she saw firsthand that Lennon knew he was being spied on by the U.S. government, and he was paranoid about it.

One of the most poignant aspects of the documentary is Pang describing how she befriended John’s son Julian, who was born in 1963, from John Lennon’s first marriage. (John Lennon and his first wife, Cynthia Lennon, were married from 1962 to 1968. Their marriage ended in divorce.)

Julian came from England to visit John Lennon on a semi-regular basis, after father and son ended an estrangement that had been going on for a number of years. Pang remembers Julian being a mischievous child but an overall good kid who craved his father’s love and attention. Pang says she encouraged John Lennon and Julian to spend as much father/son time together, which Pang says was in direct contrast to what Ono wanted.

Pang says that when Julian called, Ono would sometimes order Pang not to put the call through to John Lennon, so that Julian wouldn’t be able to talk to his father. According to Pang, Ono also ordered Pang to lie to John Lennon about how many times Julian called. In the documentary, Pang expresses deep regret about participating in these lies. Pang says that her friendship with Julian also extended to Julian’s mother, Cynthia Lennon, who died of cancer in 2015, at the age of 75.

Even when John Lennon and Pang were thousands of miles away from Ono, Pang says that Ono was a constant presence in their lives, because Ono would call at all hours of the day and night. Ono is described by Pang as being a highly manipulative control freak, who eventually got jealous that John Lennon had fallen in love with Pang. Ono wasn’t exactly celibate during the marital separation, since it’s mentioned in the documentary that her guitarist David Spinozza was Ono’s lover.

In the documentary, Pang fully acknowledges that John Lennon loved Ono too, and that he once loved his first wife Cynthia. However, Pang wants to make it clear that the love that she and John Lennon shared was real and very meaningful to both of them. Some people interviewed in the documentary, including John Lennon’s son Julian, confirm that John Lennon and Pang were in love with each other. Things were more complicated for Pang in this love triangle because John Lennon and Ono remained her employers during her entire “Lost Weekend” affair with John Lennon.

Pang says that even though John Lennon and Ono reunited in 1975, he was never completely out of Pang’s life. In the documentary, she admits that she and John Lennon would occasionally see each other and had secret, intimate trysts in the years after he and Ono had gotten back together. Pang does not mention Sean Lennon (John Lennon and Ono’s son), who was born on October 9, 1975, which was John Lennon’s 35th birthday. Like many people around the world, Pang was devastated when John Lennon was murdered on December 8, 1980.

An epilogue in the documentary mentions that Pang was married to music producer Tony Visconti from 1989 to 2003. The former spouses have two children together: Sebastian and Lara, who both are seen briefly in a childhood photo. But since this documentary is about Pang’s time with John Lennon, don’t expect to hear any details about what happened in her life during and after her marriage to Visconti.

One of the curiosities and flaws of “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” is that it has voiceover comments from several people who knew John Lennon and Pang during the Lennon/Pang love affair, but it’s unclear how much of those comments are audio recordings that were made specifically for the documentary, or if they are archival recordings from other interviews. Paul McCartney, Cynthia Lennon, Julian Lennon, Cooper, King, drummer Jim Keltner, Spinozza, photographer Bob Gruen, former Apple Corps employee Chris O’Dell, attorney Harold Seider and former ABKCO employee Francesca De Angelis (who gave Pang the job at ABKCO) are among those whose voices are heard in the documentary. Pang and Julian Lennon are the only ones seen talking on camera for documentary interviews. (Pang doesn’t make her on-camera appearance until near the end of the movie.)

“The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” has the expected array of archival video footage from various media outlets, but there’s also some whimsical animation to illustrate some of Pang’s fascinating anecdotes. She has a tendency to name drop like a star-struck fan, but it might be because she was and perhaps still is a star-struck fan of many of the people she got to hang out with during her relationship with John Lennon. Pang also says that she did not drink alcohol or do drugs during this period of time. It made her an outsider to some of the partying, but this sobriety allowed her to continue to do her job professionally when she was required to do a lot of important planning and scheduling in John Lennon’s career and personal life.

Pang briefly mentions that sometimes John Lennon was physically abusive to her when he would be in a drunken blackout, but that he was extremely remorseful and apologetic for his abuse when he was sober. In the documentary, Pang will only admit that he shoved her against a wall, but you get the feeling that the abuse was much worse than that, because at one point she says she temporarily fled from California to go back to New York because she was scared of John Lennon. He later made public apologies and expressed regrets to people whom he hurt in his life. The documentary includes a media interview with one of these regretful apologies.

Despite his flaws, Pang says that John Lennon was someone who really did try to live by his “peace and love” values that he shared with the world. He was a brilliant artist, of course. But viewers of “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” will also come away with a deeper sense that he was not only Pang’s first love but also an unforgettable friend.

UPDATE: Iconic Events will release “The Lost Weekend: A Love Story” in select U.S. cinemas on April 13, 2023.