September 13, 2023

by Carla Hay

Directed by Nailah Jefferson

Culture Representation: The documentary film “Donyale Luna: Supermodel” features a group of white and black people (with one Latino) discussing the life and career of model Donyale Luna, who broke barriers for black female models in the fashion industry.

Culture Clash: After being bullied through her teenage years in her hometown of Detroit, because of her unusual physical appearance, Luna reinvented herself and quickly became an international supermodel, but she experienced career-damaging racism and had ongoing personal problems, such drug abuse, mental health issues, and a career that burned out almost as quickly as it lit up.

Culture Audience: “Donyale Luna: Supermodel” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in biographies of unusual and underrated celebrities; the fashion industry in the mid-1960s to mid-1970s; and people who broke racial barriers in their industries.

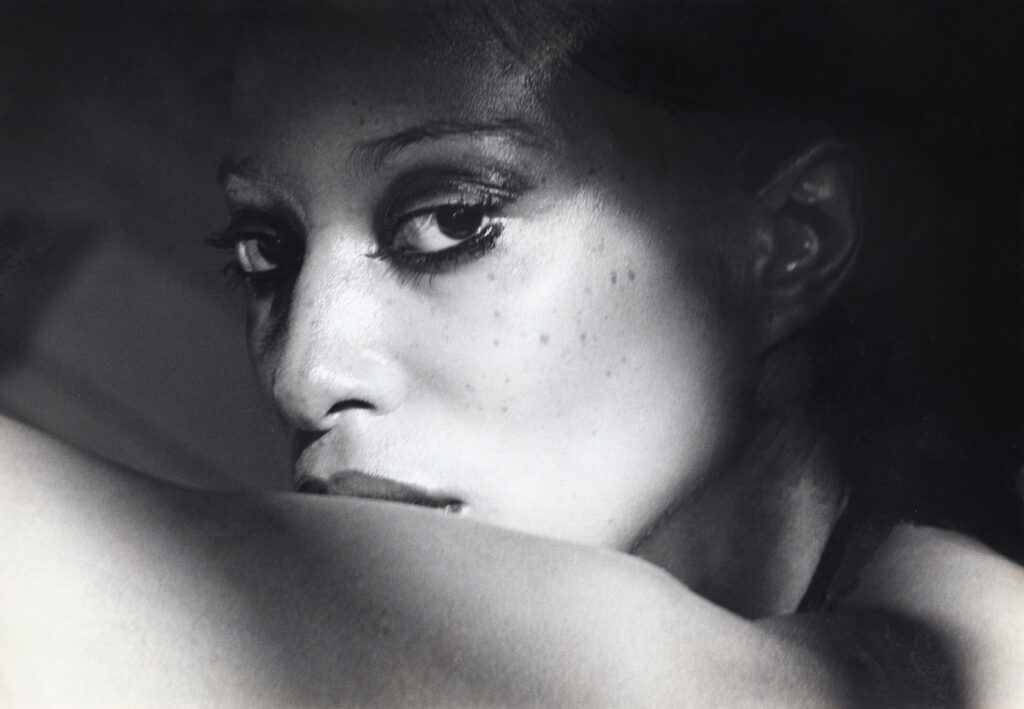

When people think of the first black woman to be on the cover of Vogue, they might think that supermodel Beverly Johnson holds that distinction. Johnson was actually the first black woman to be on the cover of American Vogue, in 1974. The first black woman to be on the cover of any Vogue was Donyale Luna, who achieved this milestone by gracing the cover of British Vogue, in 1966. Luna (whose first name was pronounced “dawn-yell”) was also the first black woman to be on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar, in 1965, but as an illustration, not in a photograph.

If you’ve never heard of Luna, you’re not alone. The documentary “Donyale Luna: Supermodel” shines a deserving spotlight on this often-overlooked model, who died of a heroin overdose in 1979, at the age of 33. Johnson, whose modeling career benefited from Luna’s racial breakthroughs, is interviewed in the documentary. Johnson admits that early on in Johnson’s career, she had never heard of Luna.

Directed by Nailah Jefferson, “Donyale Luna: Supermodel” (which had its world premiere at the 2023 American Black Film Festival) follows a traditional celebrity documentary format of having a mixture of archival footage and interviews that are exclusive to the documentary. However, Luna is such an unusual subject, and there’s such a great variety of people who are interviewed, the movie doesn’t ever feel too formulaic. It’s a riveting and well-rounded biography about a trailblazing model who never became a household name but whose impact and influence resonate for generations after her untimely passing. This documentary also explores generational trauma and pop culture.

“Donyale Luna” is artfully told in five chapters named after the cities that each defined a certain era in Luna’s life. Chapter One begins in Detroit, followed by Chapter Two in New York City, Chapter Three in London, Chapter Four in Paris, and Chapter Five in Rome. Detroit is where Peggy Ann Freeman (Luna’s real name) was born in August 31, 1945, as the middle of three sisters. She lived in Detroit through her teenage years. Her favorite movie was “West Side Sory.” Much of her childhood was scarred by bullying that she got from her some of peers because she was very tall (reportedly growing to 6’2″), slender and had big eyes. She was often called “ugly” by people who thought she didn’t fit their standard of beauty.

Adding to her unhappiness, her strict parents had a volatile on-again/off-again marriage that ended in a tragedy that won’t be described in this review, so as not reveal too much information that’s in the documentary. There’s a lot about Luna in the documentary that viewers will be finding out for the first time. There are some people interviewed in the documentary who break down in tears when talking about her, so viewers should not be surprised if they get emotional too when they watch this documentary.

Several of Luna’s family members are interviewed, including Luna’s younger sister, Lillian Washington, who says that her parents had a “history of domestic violence.” Her father Nathaniel Freeman (a longtime Ford Motor Company employee) physically abused their mother Peggy Freeman (a longtime YWCA employee), according Luna’s Detroit childhood friend Omar K. Boone, who’s interviewed in the documentary. Boone also says that when he knew Luna in her teen years, she was “unsophisticated” but a “quick learner.”

Washington and many others in “Donyale Luna: Supermodel” describe Luna as having an other-worldly beauty that would make people stop what they were doing and stare at her if she was in their presence. People who knew her best also describe her inner beauty of radiating kindness and love. However, Luna also had lifelong insecurities about the way she looked and about being accepted by other people. Several people in the documentary say that Luna habitually made up stories about herself and sought to escape in fantasy worlds that she fabricated.

The combination of these insecurities and the bullying she got as a child led her to invent the Donyale Luna persona for herself when she was a teenager. She started speaking in a European accent and pretended to be multiracial, even though she and her parents were African American. The documentary’s archival footage of her from the late 1960s shows that Luna wore piercing blue contact lenses that didn’t look like human eyes. It’s mentioned that Luna’s father disapproved of this invented persona because he felt that she was denying her African American heritage.

Washington says of Luna’s childhood and teenage years: “All the black guys thought she was crazy. They called her ‘skinny’ and ‘bony.’ They called her Olive Oyl. They hurt her to her core. I think that encouraged her to create her own persona.” Josephine Armstrong, Luna’s older sister, confirms about Luna: “She would pretend and tell stories.”

Luna’s life would change when she was discovered in Detroit by photographer David McCabe, who urged her to go to New York City (where he was based) to become a fashion model. McCabe, who is one of the people interviewed in the documentary, believes that Luna lied about her racial identity (at various times, she claimed that she was part-white, part-Latino, part Asian and/or part-Native American) because she probably felt that if people knew she was fully African American, she would experience more racism. It’s also mentioned in the documentary that Luna often talked about wishing that she had blonde hair and blue eyes.

Armed with her invented persona, Luna took McCabe’s advice and moved to New York City, in 1964. Within a few months of living in New York City, Luna was featured in the pages of major fashion magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar. She also began hobnobbing with artsy and avant-garde types. For example, McCabe says that he introduced Luna to Andy Warhol. Luna is described as someone who kept in touch with family members but also publicly denied or lied about many things about her family. The documentary mentions that she showed no interest in going back to the United States to visit her biological family after she moved to Europe.

Luna soon branched out into acting in some films, mostly supporting roles in middling movies, such as 1966’s “Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?” and 1969’s “Fellini Satyricon.” Her filmography as an actress was not extensive. According to the Internet Movie Database, Luna had credited roles as an actress in only five feature films from 1965 to 1972, with 1972’s “Salome” being the only movie where she had a starring role. She appeared as herself in several other movies.

Although she was in the public eye, Luna kept many things about herself very private and was able to fool a lot of people with her lies about her background. “Donyale Luna: Supermodel” does not mention that while she was living in New York in the mid-1960s, she was married for less than a year to an unknown actor. Very little is known about this 10-month marriage except that it ended in divorce, and Luna refused to publicly talk about this ex-husband. It says a lot about the times that she lived in, long before the Internet existed, that she was able to keep up her charade of pretending to be an exotic, multiracial European and hide many facts about her personal life.

One of her closest friends during this time was David Croland, an artist who freely admits that heavy drug use was part of their friendship and lifestyles. In the documentary, Croland says that he and Luna would regularly use marijuana, hashish and LSD. Other people in the documentary also talk about Luna’s drug abuse, which they believe was part of her need to mentally escape from her problems and try to avoid her insecurities. Family members and friends say that Luna often used drugs but was never addicted. However, it’s hard to know if that’s true, or if it’s denial from loved ones who don’t want to publicly admit that Luna could have been a drug addict.

Even with her very quick success in the fashion industry, Luna still experienced many racial barries as a black model in the mid-1960s. It was one thing to be in some fashion spreads. It was another thing to get on the cover of major magazines or get lucrative endorsement deals, which at the time were still privileges given only to white models. The documentary mentions that Luna eventually became disillusioned with the racism she experienced in the United States. The U.S. civil rights movement was going on at the same time, but she didn’t get involved in this movement or any political activism.

Luna’s career skyrocketed after she moved to London in December 1965. She would later live in Paris and then Rome. She was living in an isolated part of Italy and was in semi-retirement at the time of her death. During her years in London, she continued to hang out with the rich and famous and dated some celebrities, including Rolling Stones lead guitarist Brian Jones and actor Klaus Kinski. Luna can be seen as an assistant to a fire eater in the music variety film “The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus,” which was filmed in 1968, but wasn’t released until 1996.

Two very famous photographers are mentioned in the documentary as having the most influence on Luna’s supermodel career: Richard Avedon (an American who died in 2004, at the age of 81) and David Bailey, a Brit who is interviewed in the documentary. Bailey says that he was vaguely aware of racism in the fashion industry, but he claims that he wasn’t one of the racists. Bailey comments about Luna: “I didn’t think about her being black. She was just someone who was beautiful.”

The general consensus is that Luna found greater acceptance in Europe than she did in the United States. However, that doesn’t mean that she never stopped experiencing racism. The documentary includes a heartbreaking account of racist decisions made by Diana Vreeland (American Vogue’s editor-in-chief from 1963 to 1971) that blocked Luna from getting major career opportunities. In the documentary, former supermodel Johnson begins to cry when she hears the details. “It’s an accumulation of all the pain,” Johnson says of her crying over the racism that she, Luna and many other black people have experienced.

Other emotionally touching segments in the documentary have to do with Luna’s only child: a daughter named Dream Cazzaniga, who was only 18 months old when Luna died. Cazzaniga, who was raised by her father’s parents in Italy, reads many of Luna’s journal entries in the documentary. Luna was a talented illustrator, and the documenatry includes some of her art. Cazzaniga also candidly shares her thoughts on her memories of her mother and how she felt growing up without her mother, whose death is a “taboo” subject for the Cazzaniga family.

Because “luna” means “moon” in Spanish and in Italian, Luna often told people she had a special connection to the moon. Near the beginning of the documentary, Cazzaniga can be heard in a voiceover saying, “Growing up in Italy, I remember seeing the moon. My nanny was telling me, ‘Oh, look, that’s your mom looking from the sky.’ I never doubted that whenever I was looking at the moon, I thought that was my blessing from her.”

Later in the documentary, Dream’s Italian father Luigi Cazzaniga, who was a photographer when he married Luna in 1976, is shown being interviewed and going with Dream to visit a few of the places where he and Luna made their lives in Italy. He describes Luna as someone who loved being a mother but she was feeling increasingly unhappy with living in a remote area where she had little or no contact with her friends she used to know as a model. Luigi’s family members, whom Dream describes as conservative and religious Catholics, rejected Luna and wouldn’t allow her inside their homes. Luigi had to frequently travel because of his photographer job, so Luna was often left home alone with Dream.

Former supermodel Pat Cleveland, whose career blossomed in the 1970s around the same time as Johnson’s career, tells a harrowing story in the documentary about how Luna seemed to be mentally unraveling over all the lies and the fake persona that Luna created for herself. Cleveland describes Luna as someone who was desperately lonely and literally begging for help in the last year of Luna’s life, when Luna confessed to Cleveland that she was really an American from Detroit. Cleveland says she felt powerles to help someone whom she didn’t know every well and who was already on a downward spiral. It’s not said out loud, but it’s implied that Luna was not getting any therapy or other professional help for her mental health issues when she was living in Italy.

Several people interviewed in the documentary give cultural and historical context to why Luna’s accomplishments in the fashion industry also came with racial burdens that might have been heavier in her lifetime but still exist for many people today. Constance White, an author and former editor-in-chief of Essence, comments on white Euro-centric standards of beauty that dominate in Western culture: “It’s something that Black women have a singular experience with.” White adds that these beauty standards often have this direct or indirect message for Black women: “Everything about you is wrong.”

Other interviewees in the documentary include fashion designer/activist Aurora James, Vogue editor-at-large Hamish Bowles, Duke University art history professor Dr. Richard J. Powell, talent agent Kyle Hagler, Richard Avedon’s former assistant Gideon Lewin and fashion designer Zandra Rhodes. Three of Luna’s close friends interviewed in the documentary are Sanders Bryant, a pal who knew her from high school; actor Juan Fernandez; who describes his relationship with Luna as being like a sibling relationship; and artist Livia Liverani, who says that Luna was frequently misunderstood.

“Donyale Luna: Supermodel” is certainly not the first documentary to be about someone who had troubles coping with fame and who eventually faded into near-obscurity. However, this documentary makes a clear case for people to learn more about Luna’s legacy—not just as a model in the fashion industry but also as a loved one who changed the lives of the people who were closest to her. Fame and money can be fleeting. The areas where Luna made the most impact cannot be measured by magazine covers or monetary amounts.

HBO premiered “Donyale Luna: Supermodel” on September 13, 2023.