July 31, 2021

by Carla Hay

Directed by Jamila Wignot

Culture Representation: Taking place primarily in New York City, the biographical documentary “Ailey” features a group of white and African American people (and one Asian person) discussing the life and career of pioneering dance troupe founder/choreographer Alvin Ailey, who became one of the first African Americans to launch a world-renowned dance troupe and dance school.

Culture Clash: Ailey, who died of AIDS in 1989 at the age of 58, struggled with the idea of going public about his HIV diagnosis, and he experienced problems throughout his life, due to racism, homophobia and his issues with mental illness.

Culture Audience: Besides the obvious target audience of Alvin Ailey fans, “Ailey” will appeal primarily to people who interested in the art of fusion dance and stories about entrepreneurial artists who succeeded despite obstacles being put in their way.

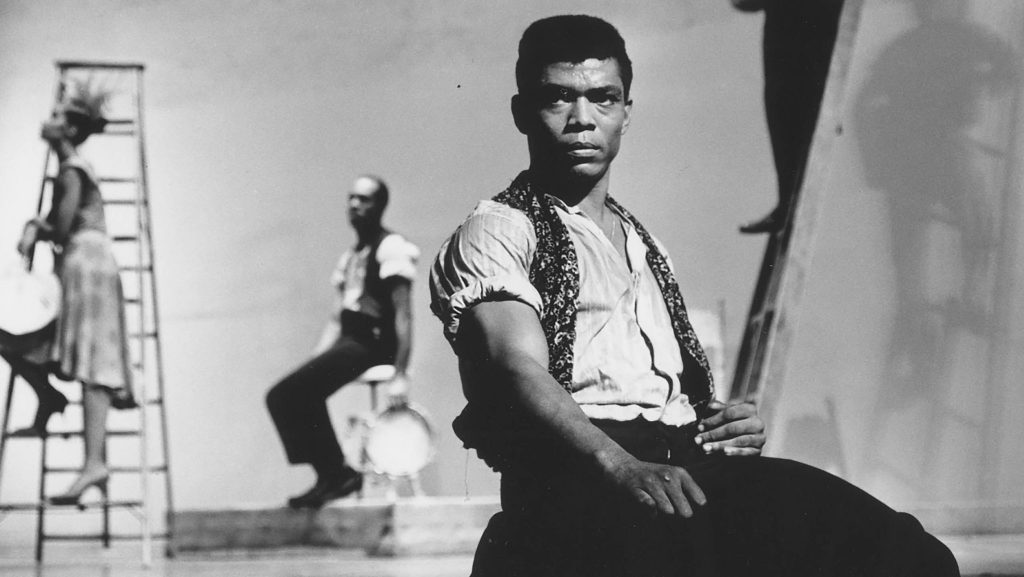

The documentary “Ailey” is a very traditionally made biography of a very non-traditional artist. Although the movie can be at times be slow-paced and dry, it’s greatly boosted by having modern dance pioneer Alvin Ailey as a very fascinating subject. Ardent fans of Ailey will get further insight into his inner thoughts, thanks to the documentary’s previously unreleased audio recordings that he made as a personal journal. The movie also does a very good job at putting into context how Ailey’s influence can be seen in many of today’s dancers and choreographers.

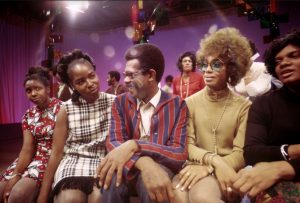

Directed by Jamila Wignot, “Ailey” had its world premiere at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival and its New York premiere at the 2021 Tribeca Film Festival. New York City was Ailey’s last hometown, where he found fame as one of the first prominent dancers/choreographers to blend jazz, ballet, theater and Afro-centric culture. His work broke racial barriers in an industry where U.S.-based touring dance troupes were almost exclusively owned and staffed by white people.

Born in the rural town of Rogers, Texas, in 1931, Ailey says in audio recordings that his earliest memories were “being glued to my mother’s hips … while she worked in the fields.” Ailey’s father abandoned the family when Ailey was a baby, so Ailey was raised by his single mother Lula, who was a domestic worker. She supported him in his dream to become a professional dancer.

Ailey’s childhood experiences were shaped by growing up poor in the racially segregated South. In the documentary, he mentions through audio recordings that some of his fondest childhood memories were being at house parties with dancing people and going to the Dew Drop Inn, a famous hotel chain that welcomed people who weren’t allowed in “whites only” hotels and other racially segregated places. Another formative experience in his childhood was being saved from drowning by his good friend Chauncey Green.

By 1942, Ailey and his mother were living in Los Angeles, where she hoped to find better job opportunities in a less racially segregated state. It was in Los Angeles that Ailey first discovered his love of dance and theater, when he became involved in school productions. A life-changing moment happened for him happened at age 15, in 1946, when he saw the Katherine Dunham Dance Company and Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo perform at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium. It sparked a passion to make dance his career. And that passion never went away, despite all the ups and downs that he encountered.

In the documentary, Ailey has this to say about watching the Katherine Dunham Dance Company for the first time: “I was taken into another realm … And the male dancers were just superb. The jumps, the agility, the sensuality of what they did blew me away … Dance had started to pull at me.”

But his interest in becoming a dancer was considered somewhat dangerous at the time, because ballet dancing was something that boys could be and still are viciously bullied over as something that’s considered “too effeminate.” Carmen de Lavallade, a longtime friend of Ailey’s, comments in the documentary on what she remembers of a young Ailey before he found fame: “He was beautiful! He didn’t dare let anyone know he wanted to be a dancer, because he would be teased or humiliated.”

But at this pivotal moment in Ailey’s life, it just so happened that Lester Horton opened the Lester Horton Dance Theater in Los Angeles in 1946. Don Martin, a longtime dancer and Ailey friend, says in the documentary that their mutual love of dance prompted Ailey to join Horton’s dance school, where Ailey thrived. Horton became an early mentor to Ailey.

The documentary doesn’t go into great detail over Ailey’s experiences as a student at the University of California at Los Angeles or when he briefly lived in San Francisco, where he worked with then-unknown poet Maya Angelou in a nightclub act called Al and Rita. Instead, the “Ailey” documentary skips right to the 1954, when Ailey moved to New York City to pursue being a professional dancer. In 1958, he founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT), which also has an affiliated school.

George Faison, an AAADT dancer/choreographer from 1966 to 1970, comments: “Alvin entertained thoughts and dreams that a black boy could actually dance” in a prominent dance troupe. Ailey shares his thoughts in his personal audio recordings: “It was a universe I could escape into, so that it would allow me to do anything I wanted to do.”

Ailey’s breakthrough work was 1960’s “Revelations,” which was a then-unprecedented modern ballet about uniquely African American experiences steeped in church traditions. The piece was revolutionary not just because it had a majority-black group of dancers and touched on sensitive racial issues but also because it used blues, jazz and gospel instead of traditional classical music. “Revelations” remains Ailey’s most famous performance work.

Mary Barnett, an AAADT rehearsal director from 1975 to 1979, remembers the impact that “Revelations” had on her: “I was moved to tears seeing ‘Revelations’ … I was studying ballet, I was studying dance. This was more of a re-enactment of life.”

Judith Jamsion—an AAADT dancer from 1964 to 1988 and AAADT artistic director from 1989 to 2011—has this to say about what “Revelations” means to her: “What took me away was the prowess and the technique and the fluidity and the excellence in the dance.” Jamison is often credited with being the person who was perhaps the most instrumental in keeping AAADT alive after Ailey’s death.

A turning point for “Revelations” was when the production went on a U.S.-government sponsored tour of Southeast Asia. It’s one thing to be a privately funded dance troupe. But getting the U.S. government’s seal of approval, especially for a tour that could be viewed as a cultural ambassador for American dance, gave AAADT an extra layer of prestige.

However, “Ailey” does not gloss over the some of the racism that Ailey encountered, including tokenism and cultural appropriation. Bill T. Jones, a choreographer who co-founded the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, has this to say about what it’s like to be an African American in an industry that is dominated by white people: “Oftentimes, black creators are used. Everybody used him [Ailey] as, ‘See, this is the progress we’re making. And see, we’re not racist, we have Alvin Ailey.'”

AAADT movement choreographer Rennie Harris (who created 2019’s “Lazarus” for AAADT) comments on Ailey’s mindset in wanting an African American social consciousness to be intrinsic to his work: “You came here to be entertained, but I have to tell my truth.” Harris adds that this way of thinkng influences his own work: “I’m still feeling the same way, as anyone would feel if you’re feeling unwanted by the [dominant] culture.”

Throughout the documentary, Harris and AAADT artistic director Robert Battle can be seen in rehearsals with AAADT dancers to show how Ailey’s legacy currently lives on with other generations of dancers. This back and forth between telling Ailey’s life story and showing present-day AAADT dancers could have been distracting, but it works well for the most part because of the seamless film editing by Annukka Lilja and Cory Jordan Wayne. The documentary has expected archival footage of Ailey interviews and past AAADT performances of Ailey’s work, such as 1969’s “Maskela Language,” 1970’s “The River”; 1971’s “Cry” and “Mary Lou’s Mass”; 1972’s “Love Songs” and 1975’s “Night Creature.”

The “Ailey” documentary includes analysis of some of Ailey’s biggest influences. It’s mentioned that “Cry” was a tribute to hard-working and supportive black women, such as his mother Lula. “Maskela Language” was inspired by the death of Ailey’s early mentor Hampton. Santa Allen, who was an AAADT dancer from 1973 to 1983, comments: “Choreography really was his catharsis.” As for his genre-defying work, Ailey says in archival footage, “I don’t like pinning myself down.”

The documentary has some commentary, but not a lot, on Ailey’s love life. He was openly gay to his close friends, family members and many of colleagues, but he avoided talking about his love life to the media. Ailey was apparently so secretive about his love life that the only serious boyfriend who’s mentioned in the documentary is a man named Abdullah (no last name mentioned), whom Ailey met in Paris and brought to New York City to live with him.

According to what’s said in the documentary, Abdullah left Ailey by climbing out of the apartment’s fire escape. The movie doesn’t mention why they broke up, but Ailey seems to have channeled his heartbreak into his work. Another aspect of Ailey’s personal life that he didn’t easily share with others was his battle with depression and suicidal thoughts. Only people in his inner circle knew about these struggles, according to what some people in the documentary say.

AAADT stage manager Bill Hammond says that by the 1970s, Ailey was a full-blown workaholic. “I think he took on too much,” Hammond comments. Other people interviewed in the “Ailey” documentary include “Lazarus” composer Darrin Ross; Linda Kent, an AAADT dancer from 1968 to 1974; Hope Clark, an AAADT dancer from 1965 to 1966; and Masazumi Chaya, an AAADT dancer from 1972 to 1966 and AAADT associate director from 1991 to 2019.

Ailey’s determination to keep his personal life as private as possible also extended to when he found out that he was HIV-positive. Several people in “Ailey” claimed that even when it was obvious that he was looking very unhealthy, he denied having AIDS to many of his closest friends, out of fear of being shunned. It was not uncommon for many people with AIDS to try to hide that they had the disease, especially back in the 1980s, when it was mistakenly labeled as a “gay disease,” and the U.S. government was slow to respond to this public health crisis.

Because dance requires a certain athleticism, having a physically degenerative disease such as AIDS was not something that Ailey wanted to be part of his legacy. According to Jones, many gay men at the time wanted to edit themselves out of the AIDS narrative. “He was part of the editing,” Jones says of Ailey.

And that shame caused Ailey to isolate himself from many of his loved ones. “He was alone,” adds Jones of Ailey not sharing much of his suffering with several people he knew. (On a side note, Jones is the subject of his own documentary: “Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters,” which was released in the U.S. a week before the “Ailey” documentary.)

But toward the end of Ailey’s life, it was impossible for him to continue to hide the truth, even though he refused to go public with having AIDS. One of the most emotionally moving parts of the documentary is when Jamison describes being with Ailey on his death bed at the moment that he died: “He breathed in, and he never breathed out. We [the people he left behind] are his breath out.”

“Ailey” is an example of documentary that’s a touching reminder that how someone lives is more important than how someone dies. The storytelling style of this documentary doesn’t really break any new ground. However, people who have an appreciation for highly creative artists will find “Ailey” a worthy portrait of someone whose life might have been cut short, but he has an influential legacy that will continue for generations.

Neon released “Ailey” in New York City on July 23, 2021, and in Los Angeles on July 30, 2021, with an expansion to more U.S. cinemas on August 6, 2021.