February 10, 2023

by Carla Hay

Directed by Brett Smith

Culture Representation: Taking place in an unnamed part of the U.S. South in 1863, the dramatic film “Freedom’s Path” features a predominantly white and African American cast of characters representing the working-class and middle-class.

Culture Clash: A young Union soldier in the U.S. Army deserts the Army after his first battle, and he is taken in by a group of African Americans who are involved in the Underground Railroad helping enslaved people and formerly enslaved people escape from those who want to keep them enslaved.

Culture Audience: “Freedom’s Path” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in a Civil War drama about race relations, even if the story is told in a somewhat formulaic and oversimplified way.

“Freedom’s Path” is a U.S. Civil War drama that’s fairly good, but not excellent. Some aspects of the movie are predictable and cringeworthy. However, the co-lead performances by RJ Cyler and Gerran Howell are admirable and are worth watching. Some of the dialogue is very hokey, but a few of the cast members bring enough personality and a certain level of believability to their characters, despite some scenarios looking very fabricated for a movie.

Written and directed by Brett Smith, “Freedom’s Path” (Smith’s feature-film debut) is based on Smith’s 2015 short film of the same name. The movie takes place in an unnamed state in the U.S. South in 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation has legally freed all enslaved people in the United States, but the Confederate states in the South refuse to acknowledge this federal legal declaration. The U.S. Civil War is raging on, as the Union military that is upholding this federal law fights against the Confederate military representing the states that want to secede from the U.S. and continue having slavery.

“Freedom’s Path” opens with a Union soldier in the U.S. Army who’s about to enter his first combat battle. His name is William (played by Howell), who is in his late teens or early 20s. William is terrified. His fear increases when he sees a commanding officer shoot and kill a soldier for desertion instead of having the soldier arrested. William barely has time to get to know anyone in his troop, although he does end up fighting side by side with another young soldier named Lewis (played by Harris Gilbertson), whose fate is easily predicted.

One of the first scenes in the movie shows that some of the Union soldiers are racist against African Americans. Some of these bigoted soldiers are shown talking with each other and complaining about the fact that the Union Army is recruiting formerly enslaved African Africans to fight alongside the white soldiers. These racists make derogatory remarks about what they think these African American soldiers will be like as legitimate members of the Army.

William is quiet and mostly keeps to himself. During his first battle, the sight of people getting killed freaks him out so much, he decides to desert the Army and never go back. Williams runs away to a wooded area, where he stabs himself with a bayonet, and he passes out from the pain. William wakes up from unconsciousness to see about five or six African American men who have found him. The men debate over what to do with William, because they don’t know if he can be trusted.

Suddenly, some white “slave catchers,” who’ve been patrolling the area, see this group of African Americans and start shooting. Two of the African Americans named Billy (played by Jasper Logan) and Dee (played by Jermaine Rivers) end up dead, but a young African American named Kitchum, nicknamed Kitch (played by Cyler), escapes with William. Kitch (who is about the same age as Williams) has to kill one of the attackers in self-defense. William isn’t very grateful that Kitch saved William’s live. He arrogantly says to Kitch: “I don’t need your help.” Kitch decides to keep helping William anyway.

Kitch brings William to his modest home, where he lives with his religious mother Caddy (played by Carol Sutton), Caddy’s partner Abner (played by Thomas Jefferson Byrd) and Kitch’s younger sister Nora (played by Mia May), who’s about 11 or 12 years old. (Sutton died in 2020, which gives you an idea how long ago “Freedom’s Path” was made before it was released.) Abner, Caddy and a colleague named Ellis Freeman (played by Afemo Omilami) are part of the Underground Railroad network that helps African Americans escape from enslavement. Caddy welcomes William into the home and does everything she can to help William recover from his injuries.

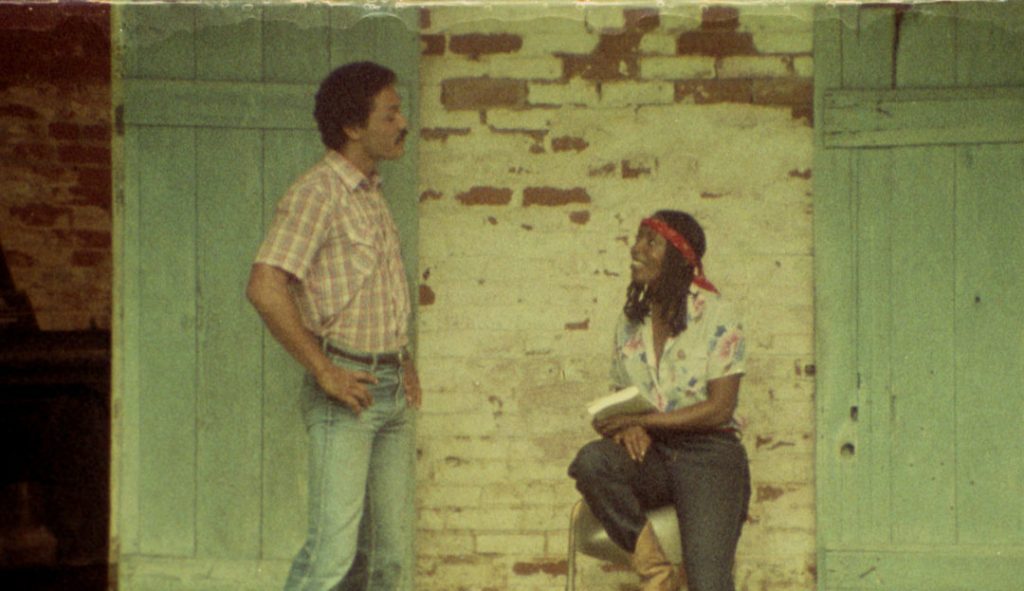

From the start, Kitch and William have a clash of personalities, since they are both stubborn and cocky. Caddy demands that Kitch show respect to William, because she says that William “is fighting for our cause.” William leads everyone to believe that his stab wounds were from combat instead of telling the truth that his stab wounds were self-inflicted. However, William does tell the truth that he doesn’t want to go back in the military. As far as Caddy is concerned, William is a war hero, and everyone should treat him that way.

Kitch isn’t entirely convinced. He’s also insulted that William called Kitch a “slave” during one of their first conversations. Kitch defensively tells William: “I ain’t been no slave since I ran out of the plantation! I’ve been doing the Lord’s work ever since.”

William and Kitch bicker and insult each other for much of their time together, but they get in a few dangerous situations where they help each other. William and Kitch start to build trust with each other. And at one point, Kitch and William make a deal with each other: William will teach Kitch how to swim, if Kitch will teach William how to play the harmonica.

The leader of the local “slave catchers” is a sadistic racist named Silas (played by Ewen Bremner) who is such a stereotypical, over-the-top villain, he’s almost a caricature. The cronies in Silas’ posse are a bunch of generic bullies who follow Silas’ orders. The movie repeats scenarios where Kitch and William are hanging out by themselves together (such as swimming in a nearby lake), and then they hear Silas and his thugs nearby, so Kitch and William have to think and act quickly in order not to be caught together.

At a certain point, “Freedom’s Path” turns into a standard chase movie, with the Civil War sidelined in the plot. The movie doesn’t do a very good job of explaining what William really wants to do or how long he wants to stay with the African Americans who have shown him this hospitality and brought him into their home. Even though William gradually earns the trust of Kitch, the fact of the matter is that this is all happening during the Civil War in the South, where white people and African Americans did not live together as equals.

And even though William is one of the movie’s lead characters, viewers still don’t find out much about him by the end of the film. “Freedom’s Path,” to a fault, treats William as a symbol of white people who are ignorant about other races until they actually spend time with people of other races, and then think, “Oh, people from other races aren’t so bad after all.” There’s a little bit of racial condescension to “Freedom’s Path,” since so much of the movie’s tone is that the African American people have to make William feel comfortable as the main priority, instead of it being more of an equal two-way street.

“Freedom’s Path” oversimplifies a lot of aspects about the Civil War, in order to make way for the movie’s hokey storyline of “let’s make all the African Americans admire William” as the top priority. For example, there could have been so many more interesting things in the movie about the Underground Railroad. Instead, the movie handles this fascinating and important part of U.S. history in a very superficial manner.

“Freedom’s Path” briefly shows a white Underground Railroad ally named Hyrum Williams (played by Michael Flynn), who secretly works with Caddy, Abner and Ellis. Hyrum pretends to be a pro-Confederate Southerner, but he’s really a pro-Union Northerner who is helping African Americans escape and hiding them in his plantation-styled home. Unfortunately, Hyrum’s screen time in the movie is so brief, viewers never really get to see the intricacies and complexities of what it must have been like for African Americans to work with white allies in the Underground Railroad.

“Freedom’s Path” has a somewhat uncomfortable way of making William’s thoughts and feelings more important than Kitch’s thoughts and feelings. And although there is some suspense in the action scenes, unfortunately, it becomes too easy to predict who will live and who will die in this story. It’s also one of these movies where someone in a fight scene sometimes stands around and talks in the middle of the fight instead of what would’ve realistically have happened: That person would’ve been killed by an opponent.

What saves “Freedom’s Path” from utter mediocrity is the credible chemistry between Cyler and Howell in portraying Kitch and William. Kitch and William’s relationship starts off as friction and evolves into a tenuous friendship that still realistically has some social barriers due to their different races, during a time in America when people of color in America were denied many basic rights that were automatically given to white Americans. With the exception of Kitch and William, the characters in “Freedom’s Path” seem very underdeveloped. There’s nothing outstanding about the acting, but it serves “Freedom’s Path” well enough when the movie trades in gritty realism for sentimental sappiness.

Xenon Pictures released “Freedom’s Path” in select U.S. cinemas on February 3, 2023. UPDATE: The Forge will re-release “Freedom’s Path” in select U.S. cinemas on September 8, 2023. The movie will be released on digital and VOD on October 6, 2023.