November 29, 2020

by Carla Hay

Directed by Alex Winter

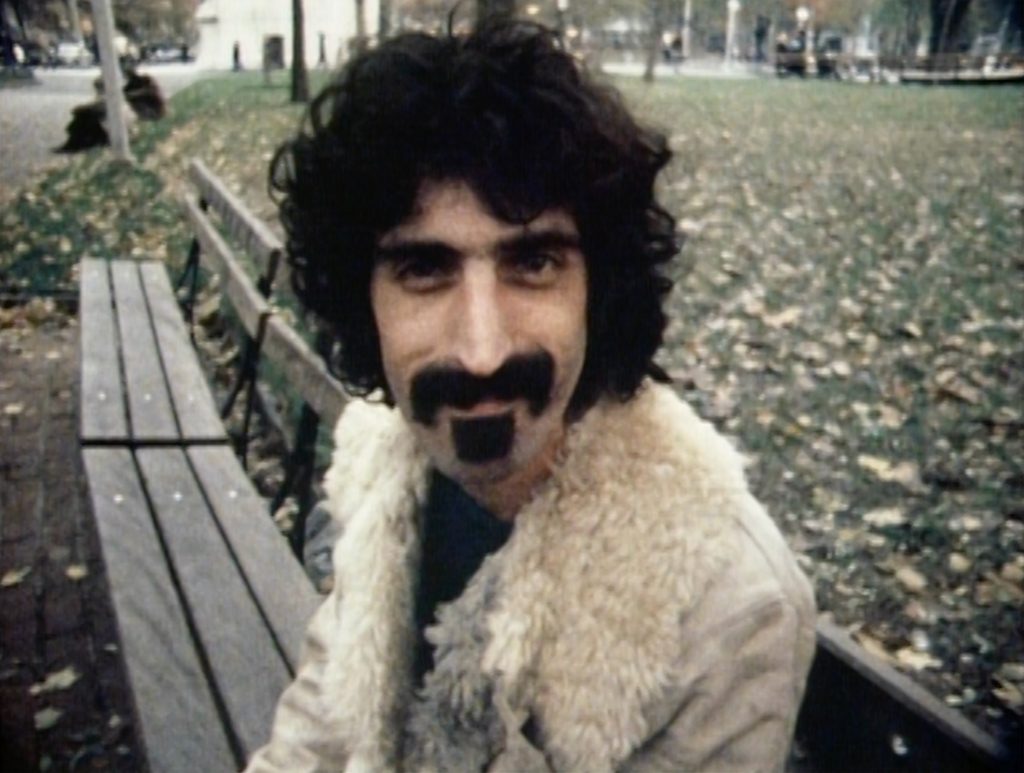

Culture Representation: The documentary “Zappa” features a predominantly white group of people (with a few African Americans) discussing the life and career of eccentric musical pioneer Frank Zappa, who died in 1993 of prostate cancer.

Culture Clash: Zappa spent most of his life and career challenging conventional norms, defying conservative mindsets, and trying to avoid mainstream success.

Culture Audience: Besides the obvious target audience of Zappa fans, “Zappa” will appeal primarily to people interested in watching an official biographical film about one of rock music’s most interesting and unique artists.

If you’re fan of eccentric musician Frank Zappa or an aficionado of independent films that make the rounds at film festivals and fly under the mainstream radar if they’re ever released, then you might know that there was a Frank Zappa documentary film called “Eat That Question” (directed by Thorsten Schütte) that got a limited release in 2016. It was an interesting but very conventional movie that was essentially a combination of archival footage and more current documentary interviews with some of Frank Zappa’s former colleagues. The documentary film “Zappa” (directed by Alex Winter) also uses the same format of combining archival footage with new interviews about Frank Zappa, who passed away of prostate cancer in 1993, at the age of 52. Neither film is as groundbreaking as its subject, but the “Zappa” film has a major advantage over “Eat That Question,” because “Zappa” has a lot of never-before-seen footage directly from the Zappa family archives.

That’s because the “Zappa” documentary was authorized by the Zappa family. Ahmet Zappa, one of Frank’s sons, is one of the producers of the movie. There’s a treasure trove of content in the movie that is sure to thrill Zappa fans who can’t get enough of seeing previously unreleased things related to the prolific artist. “Zappa” took several years to get made because the filmmakers first “began an exhaustive, two-year mission to preserve and archive the vault materials. When this was completed, we set about making the film,” according to what director/producer Winter says in the movie’s production notes.

How long did it take for “Zappa” to get made and finally released? Frank’s widow Gail Zappa, one of the interviewees who’s prominently featured in the movie for the “new interviews,” died in 2015, at the age of 70. (The movie’s end credits say that the documentary is dedicated to her.) Therefore, the movie looks somewhat dated, but it doesn’t take away from the spirit of the film, which is a fascinating but sometimes rambling portrait of Frank. (The “Zappa” documentary clocks in at 129 minutes.)

After the opening scene of Frank performing at the Sports Hall in Prague in 1991 (his last recorded guitar performance), the next approximate 15 minutes of the movie consists of a compilation of images depicting Frank’s youth, with Zappa’s voice from archival interviews as voiceover narration. He talks about his childhood and how he decided to become a musician. Diehard fans of Frank already know the story, but it’s told in Frank’s voice with a mixture of nostalgia and anger.

Born in Baltimore on December 21, 1940, Frank grew up as the eldest child of four children, in a fairly strict, middle-class home with his parents Francis and Rosemarie Zappa, although Frank describes their family as “poor” in one of the archived interviews. Francis Zappa worked at Edgewood Arsenal, a company that made poisonous gas during World War II. The family then relocated to California, where Frank’s father took a job at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey to teach metallurgy.

His parents did not encourage Frank’s interest in music. In fact, they downright disapproved of it because they didn’t think it was a stable way to make a living. Frank, who was famous for being iconoclastic, showed early signs of rebellion as a teenager when he says that he took some explosive powder and attempted to blow up his high school. It’s never really made clear in the documentary if that really happened, or if it’s just part of Zappa folklore.

It was while he was a teenager that Frank says he became obsessed with film editing. He would edit the family home movies by inserting quirky footage into it, some of which is shown in the documentary. (The home movies include Frank and his siblings dressed as zombies and pretending to attack each other.) As an adult, Frank directed many short films, music videos and some feature-length movies, most notably the 1971 musical film “200 Motels.”

One of Frank’s earliest musical influences was composer Edgard Varèse, who was known for his emphasis on rhythm rather than form. In a voiceover from an archived interview, Frank says about Varèse: “I wanted to listen to the man who could make music that was strange.” And that’s exactly how many people would describe Frank’s music when he eventually developed into his own artist.

By the time Frank was a teenager, the Zappa family had moved south of Monterey to the city of Lancaster, where Frank attended Antelope Valley High School. It was in high school that he met a fellow eccentric named Don Van Vliet, who’s better known by his stage name Captain Beefheart, who would become one of Frank’s most famous musical collaboraters.

As a teenager, Frank became an enthusiast of R&B and blues music, with great admiration for musicians such as Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Elmore James and Johnny “Guitar” Watson. Frank’s first band in the mid-1960s was called The Blackouts, and they played R&B and blues. The Blackouts were considered radical at the time because they were a racially mixed group of white and black musicians. The Blackouts mostly did cover songs, but Frank’s ultimate goal was to write and record his own original music.

He took a day job writing and illustrating greeting cards in his own quirky style. A few of his greeting cards from 1964 and 1965 are shown in the documentary. One of them was a “get well” card that said on the front, “Nine out of ten people with your illness …” and then inside the card it ended with the words “… are sick.” Another card said on the front: “Captured Russian photograph shows evidence of Americans’ presence on the moon first.” Inside the card, there was an illustration of a moon crater bearing a sign that reads, “Jesus Saves.”

A turning point in Frank’s life was when he bought a small recording studio in Rancho Cucamonga, California, and named it Studio Z. The studio (which had “no bathtub, no shower and no hot water,” he says in an interview) was mostly for music, but also rented out space for filmmaking. A group of men rented Studio Z’s services because they wanted to make a quasi-“stag film” with the men dressed in drag, but with no actual nudity or sex, according to Frank in an archival interview. The local police heard about the movie and arrested Frank, who says that he got sentenced to six months in jail (with all but six days suspended) and three years of probation.

Frank says in an archived interview that this negative experience with the law taught him all he needed to know about the political system. All he wanted to do was to make music, and he knew that living in a small town wasn’t suited for him. He eventually moved to Los Angeles.

In 1965, Frank founded the Mothers of Invention, the avant-garde rock band of rotating musicians that he performed with for the majority of his career. Tom Wilson (an African American producer) signed the band to Verve Records. The Mothers of Invention’s debut album “Freak Out!” (released in 1966) is considered a seminal recording for anything that could be considered “alternative rock.”

Frank’s quick courtship of Gail is described in the documentary as Gail being introduced to Frank by Pamela Zarubia, who was his roommate at the time, and a few days later Frank asked Gail if she wanted to have sex with him. (There’s archival footage of Zarubia describing this very fast and forward courtship.) Frank and Gail married in 1967 and had four children together: daughter Moon, son Dweezil, son Ahmet and daughter Diva. The children are not interviewed in the movie.

For whatever reason, the documentary never mentions Frank’s first marriage to Kay Sherman. (Their 1960 to 1964 marriage ended in divorce. There were no children from this marriage.) It could be a situation of the second wife wanting to erase the first wife from the family history. As is the case with authorized documentaries of dead celebrities, the filmmakers usually have to go along with whatever the celebrity’s family estate wants to put in the film and what they want to leave out.

At any rate, Frank was very open in many interviews by saying that he was not a monogamous husband and that his time spent away from home as a touring musician often took a toll on his family life. In the documentary, Gail comments on these difficulties in her marriage by sharing her secret to the relationship’s longevity when it came to any infidelity: “Don’t talk about it.”

Ruth Underwood, who was in the Mothers of Invention off and on from 1967 to 1976, says in the documentary that there were two sides to Frank: the doting family man and the raunchy rock star—something that she calls “a polarity of passion.” She elaborates: “He couldn’t fucking wait to get on the road. But then, he was very happy to come home, just to feel safe again.”

The Zappa family household, where Frank always had a home studio, became a hub of activity for the “freaks” of Los Angeles’ Laurel Canyon when the family lived there in the late 1960s. One of the musical acts that he produced was an all-female singing/performance group called The GTO’s (self-described “groupies” whose band acronym stood for Girls Together Outrageously), who recorded their first and only album with Zappa. Pamela Des Barres, who was a member of The GTO’s, says that famous American and British musicians would always like to hang out in the Zappa home because of all the strange and interesting things going on there. “He was the centrifugal force of Laurel Canyon,” remembers Des Barres. “It was the center of the world at that point.”

However, things got too weird (even for the Zappas) when a group of hippies moved nearby: the Manson Family cult led by Charles Manson, who would later become notorious for masterminding the 1969 murders of several people, including actress Sharon Tate. Even though at the time the Zappa family lived in Laurel Canyon, no one knew how dangerous the Manson Family would become by committing these murders a few years later, Gail says in the documentary that these Manson Family neighbors always made her feel uneasy when she would see them. And so, the Zappa family eventually moved out of Laurel Canyon.

Several of the musicians who worked with Frank are interviewed in the film. They describe him as extremely prolific and talented but someone who was an unrelenting taskmaster (making band members rehearse 10 to 12 hours a day, several days a week, including holidays) who rarely gave praise and almost never showed any affection. He could be dismissive and sometimes cruel. By his own admission, Frank didn’t make friends easily, and he didn’t care about being popular. On the other hand, according to Gail, there were some people who earned Frank’s loyalty in his life, and he was very loyal to them in return—almost to a fault.

In 1969, when Zappa decided to abruptly disband the Mothers of Invention’s original lineup, original band member Bunk Gardner says that the band didn’t even get two weeks’ notice. They were just suddenly informed that their services were no longer needed. Frank would later invite some of the original Mothers of Invention band members back into the group, but he always like to rotate the lineup and not keep it too permanent until the band ended for good in the mid-1970s.

Some of the musicians who were in the Mothers of Invention included Aynsley Dunbar, Terry Bozzio, George Duke, Jean-Luc Ponty, Adrian Belew, Peter Wolf, and The Turtles co-founders Howard Kaylan and Mark Volan. And the group performed with several guests, including John Lennon, Yoko Ono and Eric Clapton. (The documentary has footage of Lennon and Ono on stage with the Mothers of Invention in 1971.)

Ruth Underwood believes that Frank was seemingly insensitive to other people’s needs and feelings because “I think he was so single-mindedly needing to get his work done.” Later, she gets emotional and teary-eyed when she describes a touching moment she had with Frank toward the end of his life that showed how he mellowed with age and had to face his mortality after being diagnosed with cancer.

Despite Frank’s reputation for being a bossy and gruff control freak, there were some good times too, and the people who worked with him say that the music made it all worthwhile. Ruth Underwood’s ex-husband Ian Underwood, a Mothers of Invention member from 1967 to 1975, says about performing live as a member of the band: “Each show was like a composition.”

Steve Vai, who was in Frank’s band from 1980 to 1982, comments about his time in the group: “When I was in it, I was a tool for the composer. And he used his tools brilliantly.” Other former colleagues of Frank who are interviewed in the film include musician Scott Thunes (who worked with Frank from 1981 to 1988), accountant Gary Iskowitz, musician Ray White (who worked with Frank from 1976 to 1984) and engineer David Dondorf.

Gardner also remembers the camaraderie among the band members: “It was exciting in the beginning, but of course it was musically difficult … I’m not a weirdo or any of those other things. But when you get around people who are naturally funny that do weird things, I ended up feeling comfortable.” Mike Keneally, a musician was in Frank’s band from 1987 to 1988, remembers comedian Lenny Bruce as being a big influence on Frank.

Frank wasn’t a typical rock star in other ways besides his music. He was very vocal about his personal choice not to do drugs. And he had no patience for anyone who let their drug use get in the way of being at their best. (He was a heavy smoker of cigarettes though.) Frank didn’t go as far as preach to people not to do drugs, since he was firm believer in individual freedoms, but he made it clear that he looked down on people who used drugs that made them “stupid.”

And just like Frank himself, his fan base was somewhat hard to categorize. The documentary shows a 2006 interview with Alice Cooper (one of the many musicians who worked with Frank) commenting: “He had the freaks and the extremely intelligent and the very artsy people behind him. And there was the whole middle who just didn’t get it.”

Despite being known as an avant-garde creative artist, Frank was also very business-minded. He didn’t care about having hit records, but he did care about making enough money to fund his art. The documentary includes clips from several archival interviews of Frank expressing that belief in various ways.

He founded his own record labels (including Bizarre Records, Straight Records and DiscReet Records) and made a lot of money through merchandising, with Gail handling a lot of the business. Frank’s bitter late-1970s split from longtime distributor Warner Bros. Records is given a brief mention in the film. Although he worked with major record companies, he always had an entrepreneurial spirit when it came to releasing his music. And he wasn’t afraid to go outside of his comfort zone, such as recording and conducting classical music and other orchestral music. The documentary includes some footage of him working with the Kronos Quartet.

Gail says in the documentary that even though Frank believed that smart musicians should care about being paid for their work, he also believed that getting rich shouldn’t be the main motivation to make music, because most musicians can’t make a living as full-time artists. She comments on being a full-time musician: “You have to be out of your mind to begin with to take it on. There’s no guarantee that you’ll be able to earn an income. No one cares what composers do. And everything is against you, which makes the odds pretty fantastic.”

As for Frank’s talent as a visual artist, he wanted to design all of the Mothers of Invention album artwork from the second album onward, but he changed his mind when Cal Schenkel came along and ended up being the Mothers of Invention’s chief art collaborator. “They [Frank Zappa and Schenkel] created a world together,” says Keneally.

Another visual artist who was highly respected by Frank was claymation animator Bruce Bickford, who is interviewed in the film and whose work is included in the documentary. Bickford comments on Frank: “He was impressed with the number of figures I could sustain in animation in one shot.”

“Zappa” is told in mostly chronological order, so it isn’t until toward the end of the film that his 1980s fame is covered. Frank had the biggest hit of his career with “Valley Girl,” a 1982 duet with his then-14-year-old daughter Moon that was a parody of the teenage girl culture of California’s San Fernando Valley. Ruth Underwood says that the idea for “Valley Girl” came about after Moon slipped a preoccupied Frank a note underneath his door, asking him if he remembered her because he seemed too busy to pay attention.

In the note, Moon described the type of lingo that she was hearing from Valley girls and what was important to these teens: clothes, boys and hanging out at the Sherman Oaks Galleria shopping mall. Frank thought it would be a great idea to make it into a song recorded by him and Moon, who at the time, went by her first and middle names Moon Unit. And the rest is history.

“Valley Girl” became a surprise hit, peaking at No. 32 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The song was also nominated for a Grammy. And suddenly, Frank and Moon became celebrities who could be heard on mainstream radio and interviewed on shows like “Entertainment Tonight.” The documentary has footage of the Zappa family doing a photo shoot for Life magazine around the time that “Valley Girl” was a hit.

The song inspired the 1983 “Valley Girl” film, starring Deborah Foreman and Nicolas Cage, but the “Zappa” documentary doesn’t include any mention of Frank’s unsuccessful legal fight to prevent the movie from being made. The Zappa family has nothing to do with this “Valley Girl” movie or the 2020 movie musical remake of “Valley Girl.”

Frank’s other notoriety in the 1980s came from being a very outspoken protester against the Parent Music Resource Center (PMRC) and its efforts to put warning labels on records that have sexually explicit or violent lyrics. During this period of time, Frank’s wild and freaky hair and clothes from the 1960s and 1970s were gone and replaced with shorter hair and business suits that he would wear when he testified in front of the U.S. Congress or when he would do TV interviews speaking about the subject. About his image change, he was honest about who he was: a middle-aged dad who needed to be taken seriously if he wanted to get his point across to politicians and other officials who were in charge of making decisions that affected the music industry.

Although the PMRC achieved its goal of having the music industry voluntarily place warning labels on records, Frank toyed with the idea of becoming a politician. He talks about it in a few interview clips shown in the documentary, and he seemed to have mixed feelings about running for president of the United States. On the one hand, he seemed open to the idea because he wanted to make big changes in American society. On the other hand, he expressed a distaste for how a lot of the government is run and not liking the idea of having to live in the White House.

He never did run for public office, but Frank’s 1990 visit to what was the country then known as Czechoslovakia was a life-changing experience for him. He was welcomed as a hero of democracy, and Czechoslovakia appointed him as a Czech ambassador for U.S. trade. Apparently, this appointment didn’t sit well with influential members of the U.S. government, because Czechoslovakia eventually rescinded that title from him.

Frank’s health problems are included in the documentary in a respectful way. He was confined to a wheelchair for about nine months after being physically attacked on stage by an audience member in 1971. The recovery experience made him “find out who my real friends are,” as he said in a TV interview that’s shown in the film. The documentary includes footage of Frank in the final two years of his life, in the studio and on stage, such as his last concert appearance in 1992 in Frankfurt, Germany, where he got a standing ovation that lasted for more than 20 minutes.

The “Zappa” documentary could have used tighter editing, but overall the movie is a fairly even-handed look at the life of a unique and influential artist. The movie doesn’t really reveal much about his life or his personality that Frank’s diehard fans didn’t already know about, based on all the interviews he gave over the years. What makes this film stand out is the rare footage of Zappa at home, in the studio and on stage, because this footage gives some meaningful context to the very full life that he led.

Magnolia Pictures released “Zappa” in select U.S. cinemas, digital and VOD on November 27, 2020.