September 23, 2022

by Carla Hay

Directed by Reginald Hudlin

Culture Representation: The documentary film “Sidney” features a predominantly African American group of people (with some white people and one person of Middle Eastern heritage), including actor/filmmaker/humanitarian Sidney Poitier, from the entertainment industry and from Poitier’s family, who all discuss Poitier’s life and legacy.

Culture Clash: Poitier, who broke many racial barriers in his long and esteemed career, experienced poverty in his childhood, racism from white people, and accusations of being a “sellout” from some members of the African American community.

Culture Audience: “Sidney” will appeal mainly to people who are fans of Poitier and real stories of people who became icons after experiencing many hardships.

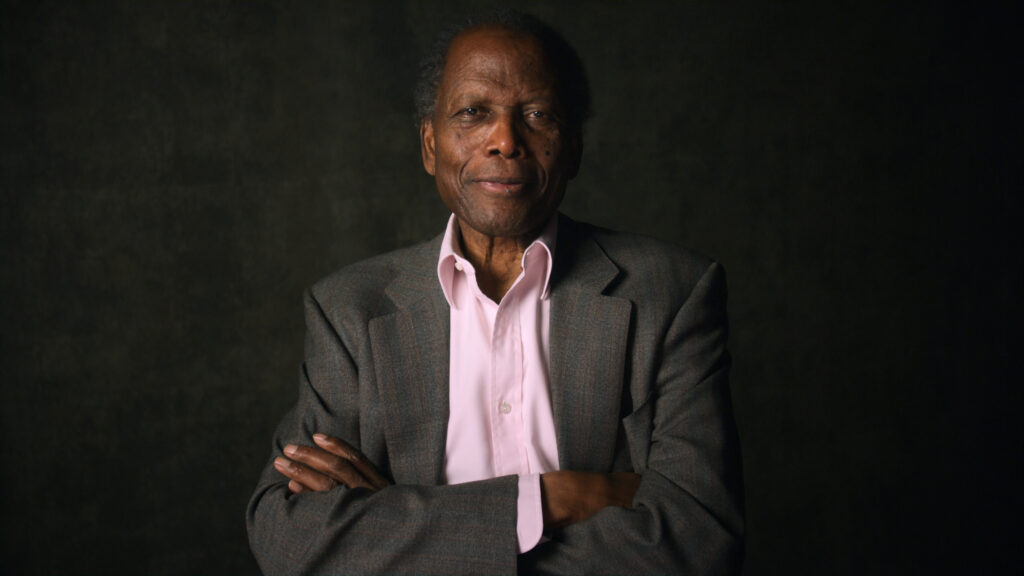

The admirable documentary “Sidney” follows a very traditional format, but in telling the story of the extraordinary Sidney Poitier, it’s no ordinary biography. Poitier’s participation gives this documentary a heartfelt resonance that’s unparalleled. It’s the last major sit-down interview that he did before he died. He passed away at the age of 94, on January 6, 2022.

Directed by Reginald Hudlin, “Sidney” is a documentary that includes the participation and perspectives of several members of Poitier’s family, including all six of his daughters and the two women who were his wives. Some journalists and historians weigh in with their opinions, but the documentary is mostly a star-studded movie of entertainers who were influenced or affected by Poitier in some way. “Sidney” had its world premiere at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival.

One of the celebrity talking heads in the documentary is Oprah Winfrey, who is one of the producers of “Sidney.” She talks openly about how important Poitier was to her as a mentor during her own rise to fame as a TV talk show host and later as the owner of a media empire. Toward the end of the film, Winfrey begins crying when she says how much she misses Poitier. It’s a moment where viewers will have a hard time not getting tearful too.

Most people watching “Sidney” will already know something about Poitier before seeing this movie. His 2000 memoir “The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography” covers a lot of the same topics that’s covered in “Sidney.” But to see him talk about his life story and experiences in what no one knew at the time would be his last major interview brings an special poignancy to this documentary.

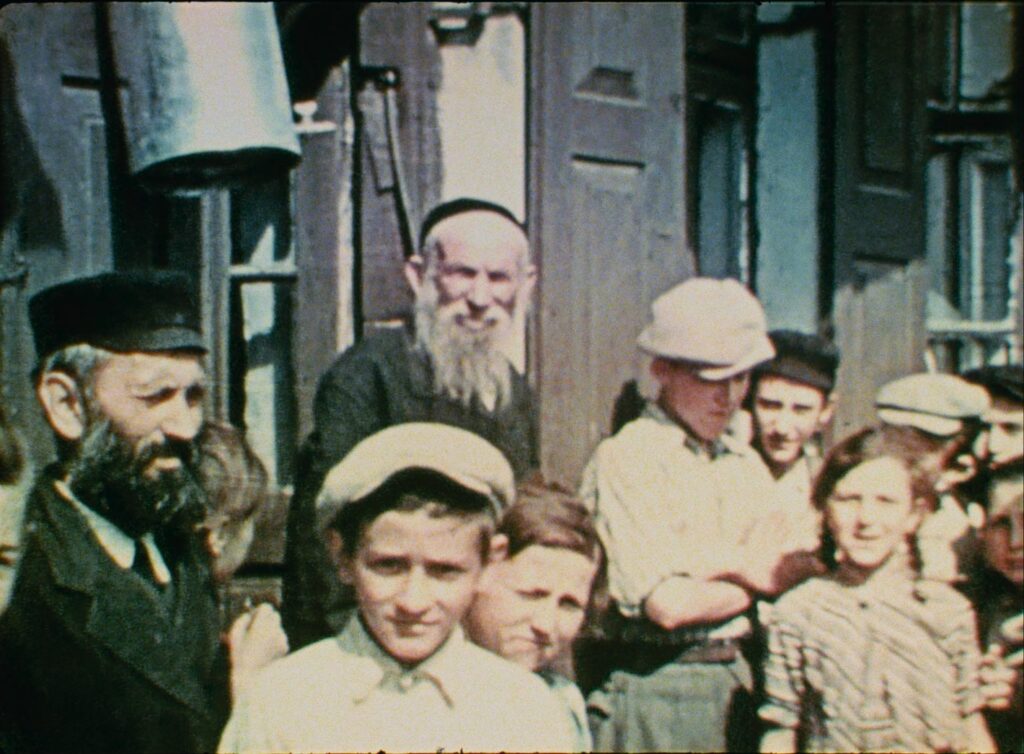

Born in Miami, on February 20, 1927, Poitier grew up in poverty in the Bahamas, his parents’ native country. He was the youngest of seven children born to famers Reginald and Evelyn Poitier. “I wasn’t expected to live,” Poitier says of his birth. “I was born two months premature.”

Poitier says that he was so sickly at birth, his father brought a shoe box into the birth room because the family thought that baby Sidney would have to be buried in the box. Sidney’s frantic mother took newborn Sidney to different places in the neighborhood to find anyone who could help save his life. Evelyn found a female soothsayer who said she couldn’t give any medical help, but she predicted that Sidney would be find and he would grow up to be an influential person who would find fame and fortune.

Getting to that point wasn’t easy and it was far from glamorous. In 1942, at the age of 15, his father Reginald had Sidney move to Miami and live with an aunt and uncle, because Sidney had a friend who was a juvenile delinquent, and Reginald feared that Sidney would fall in with a bad crowd. Little did Sidney know that he would be facing a different type of damage to his innocence.

In Miami, Sidney went through major culture shock and racism that drastically changed his perspective of the world. “Within a few months, I began to switch my whole view of life,” Sidney says of moving from the Bahamas to Miami. He got a part-time job as a delivery boy, and he tells a story of not understanding why a white woman who got one of his deliveries demanded that he only go to the back of the house to make the delivery. Later, when he heard that members of the Ku Klux Klan were looking for him because of this incident, he got so unnerved that he decided to leave town.

But even that attempted trip was fraught with danger, because he was harassed and stalked by white police officers, who didn’t want to see a black male having the freedom to travel wherever he wanted. Needless to say, when Sidney heard that black people had better work opportunities in New York City, he soon relocated to New York City, where he discovered his love of acting.

Life in New York City was a very difficult challenge too. For a while, Sidney was homeless and had to sleep in a public bathrooms. He got a job as a dishwasher while also taking acting classes, which he says he was like being in useful therapy, where he could pour all of his emotions into fictional characters. He read books and listened to radio stars (especially Norman Brokenshire) to learn how to speak with an American accent.

His motivation to become a great actor came from being rejected by audiences at the American Negro Theater because, as a black man, he was expected to sing, dance and be funny. Sidney wanted to be a serious dramatic actor. One of the American Negro Theater officials told Sidney that he should just give up acting altogether. We all know what happened after that Sidney got that horrible advice. It’s an excellent example of how someone can turn failure and discouragement into a triumph.

It’s mentioned several times in the documentary that Sidney’s guiding principles were to do work that would make his parents proud. That’s why, throughout his career, he rejected doing roles that were demeaning to black people. He made his film debut as a doctor in the 1950 drama “No Way Out.” And the rest is history.

The year 1950 was also the year that Sidney married his first wife, Juanita Hardy Poitier. The couple had four daughters together: Beverly, Pamela, Sherri and Gina. During the marriage, Sidney had a nine-year on-again/off-again affair with actress Diahann Carroll (who died of cancer in 2019), his co-star in 1959’s “Porgy and Bess.” Poitier and Carroll later co-starred in 1961’s “Paris Blues.” Sidney and Juanita’s marriage eventually ended in divorce in 1965. Sidney describes this period of time of his life as one of career highs but personal lows. He also expresses remorse about how his marital infidelity and divorce hurt his family.

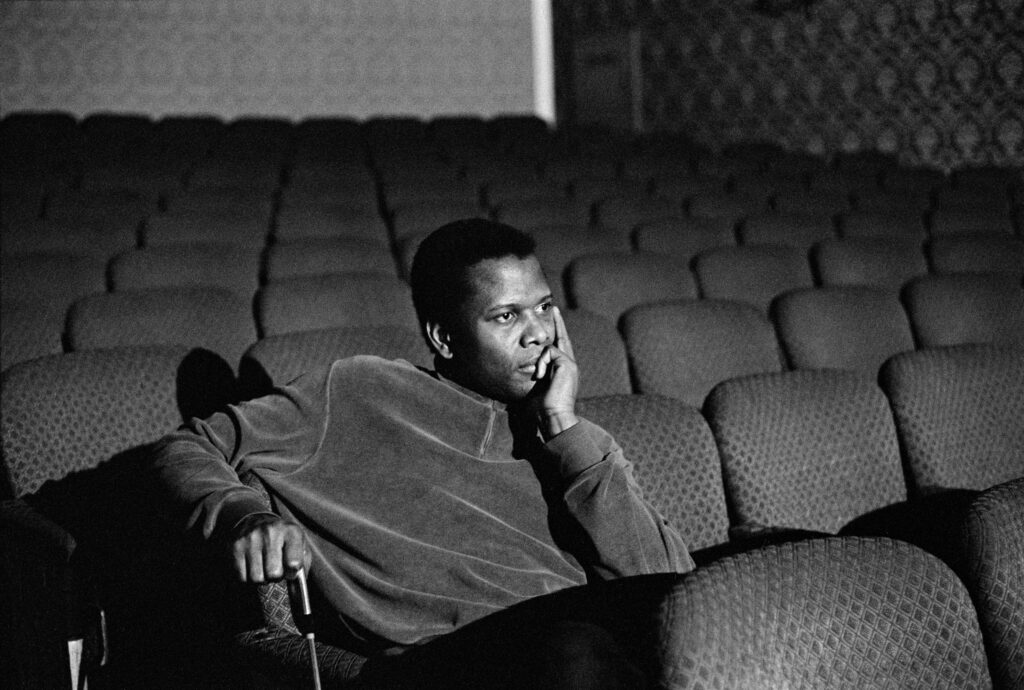

The documentary gives chronological highlights of his career in movies and in theater. For his role in 1958’s prisoner escapee drama “The Defiant Ones” (co-starring Tony Curtis) Poitier became the first black person to get an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. It’s mentioned in the documentary that the movie’s ending was somewhat controversial among black people, because some critics thought it was pandering to a what’s now known as a “magical Negro” stereotype.

For his role in 1963’s “Lilies in the Field,” Sidney became the first black person to win Best Actor at the Academy Awards. It was a role that was originally turned down by Poitier’s longtime friend Harry Belafonte, who was busy with a music career. Belafonte also thought that the “Lilies in a Field” role (a black man who’s a nomadic worker befriends a group of white German nuns) was too corny and subservient. Belafonte does not do an on-camera interview for this documentary, but he can be heard in a few voiceover comments.

In 1967, Sidney was a bona fide superstar as the lead actor in critically acclaimed hit movies “In the Heat of the Night,” “To Sir, with Love” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.” All were groundbreaking in different ways in depicting race relations in cinema. And the fact that they were box-office successes are indications that times were changing, and the world was ready to see these types of movies.

For his “In the Heat of the Night” role, Sidney played a confident police detective named Virgil Tibbs, who demanded respect from everyone around him. There’s a famous scene in the movie where Virgil is slapped in the face by a racist white man for no good reason. In response, Virgil slaps the man in the face. At the time, it was rare for a movie to show a black man defending himself from this type of racist hate.

In “To Sir, With Love,” Sidney played a schoolteacher in East London who has to be the instructor for unruly white teenagers. It was another on-screen rarity at the time to see a black man in charge of white children. And in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” Sidney had the role of a doctor who gets engaged to a white woman after a whirlwind romance, and she brings him home to introduce him to her shocked parents for the first time.

The documentary repeatedly mentions that for every accolade and trailblazing accomplishment that Sidney received, there were critics who thought that he wasn’t being “black enough.” Winfrey, who’s gotten the same type of criticism, remembers meeting Sidney after she became famous and was very in awe of meeting him. She says she asked him how he dealt with the “not black enough” criticism, and he gave her advice that she never forgot: He told her that as long as she was doing what felt right in her heart, that’s all that mattered.

Sidney and Belafonte, who were as close as brothers, were at the forefront of the entertainment industry’s involvement in the U.S. civil rights movement. However, the two friends had occasional estrangements over various issues. One of these issues was that Sidney tended to be more politically conservative than Belafonte when it came to the support of Black Power groups that advocated for preparing for a race war and all the violence associated with war, especially after the devastating 1968 deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. In his senior years, Sidney became an ambassador representing the Bahamas.

The documentary mentions that by the early 1970s, the Black Power movement and blaxploitation movies made Sidney seem like a somewhat a has-been and outdated movie star to some people. He began to shift his attention more to directing and producing movies. His feature-film directorial debut was the 1972 Western “Buck and the Preacher,” in which he co-starred with Belafonte. It’s mentioned in the documentary that as a filmmaker, Sidney practiced what he preached in the civil rights movement and gave plenty of jobs to people of color in front of the camera and behind the camera.

The 1970s decade was also period of change in his personal life: Sidney and Canadian actress Joanna Shimkus fell in love while co-starring in the 1969 movie “The Lost Man.” In the “Sidney” documentary, Shimkus Poitier says she never heard of Sidney until she got the role in the movie, whose love story plot mirrored their own romance. The couple had daughters Anika and Sydney Tamiia, and then wed in 1976, and remained married until Sidney’s death.

In the documentary, Sidney says that his second marriage also gave him a second chance to be a better husband and father. His daughters from his first marriage became part of his blended family. Sydney Tamiia (who is now known as Sidney Poitier Heartstrong) mentions that her parents made sure that she and her sister Anika grew up with other interracial families, with Quincy Jones and his interracial family being close friends with the Poitier family.

Jones is one of numerous stars who have joyous and insightful things to say about Poitier. Other entertainment celebrities who are interviewed include Denzel Washington, Halle Berry, Spike Lee, Robert Redford, Morgan Freeman, Lenny Kravitz, Barbra Streisand, Louis Gossett Jr., Katharine Houghton and Lulu. Also interviewed are civil rights activist/former politican Andrew Young, writer/historian Greg Tate, civil rights activist Rev. Willie Blue, journalist/historian Nelson George and University of Memphis history professor Aram Goudsouzian, who wrote the 2004 biography “Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon.”

All of these interviewees have wonderful things to say and are often very witty when saying these things. That is not too surprising. However, what will stay with viewers the most is that they wouldn’t be saying those things if Sidney had not had such an exemplary life. His impact is immeasurable and goes far beyond the entertainment industry. He’s an unforgettable role model of hope, dignity and progress in striving for a better world.

Apple Studios released “Sidney” in select U.S. cinemas and on Apple TV+ on September 23, 2022.