February 28, 2024

by Carla Hay

“Pathological: The Lies of Joran van der Sloot”

Directed by Christopher Cassel

Some language in Spanish with subtitles

Culture Representation: Taking place in Peru, Aruba, the United States and the Netherlands, the documentary film “Pathological” features a group of of white and Latin people representing the working-class and middle-class and discussing cases involving convicted murderer Joran van der Sloot.

Culture Clash: After being the main suspect in the 2005 disappearance of 18-year-old American tourist Natalee Holloway in Aruba, Dutch native Jordan van der Sloot (who spent most of his youth living in Aruba) takes Holloway’s loved ones, investigators and the media on “wild goose chases” about what happened to Holloway, even after he is convicted of murdering another young woman in Peru, in 2010.

Culture Audience: “Pathological: The Lies of Joran van der Sloot” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in getting details of the horrible manipulations that van der Sloot inflicted on people behind the scenes in relation to his crimes.

“Pathological: The Lies of Joran van der Sloot” is a well-researched documentary that ultimately doesn’t reveal anything new about this notorious murderer, but it does give a very insightful look at how he manipulated people. This documentary film can serve as a helpful way for people to look for warning signs in predatory criminals, in order to prevent becoming possible victims. “Pathological: The Lies of Joran van der Sloot” also shows how the media’s role in covering a famous crime can both hurt and harm the case.

Directed by Christopher Cassel, “Pathological: The Lies of Joran van der Sloot” was produced by NBC News Studios, which is why much of the archival footage comes from NBC News. Peacock (the streaming service distributing this documentary) and NBC both share the same parent company: NBCUniversal. However, this documentary has several exclusive, new interviews that give context and commentary about how certain events related to Joran van der Sloot. This documentary does not glorify him or make him look sympathetic.

Most people first heard about van der Sloot because he was the main suspect in the 2005 disappearance of Natalee Holloway (affectionally nicknamed “Hootie”), an 18-year-old American tourist from Alabama who had recently graduated from high school and was on vacation with several of her friends in Aruba. She had plans to be a pre-med student and had a full scholarship to attend the University of Alabama. The people who knew Natalee who are interviewed in the documentary—including her younger brother Matthew Holloway—describe her as a fun-loving and caring person. In the documentary, Matthew shares a heartbreaking memory of his father desperately searching for Natalee’s body with his bare hands at a garbage landfill in Aruba.

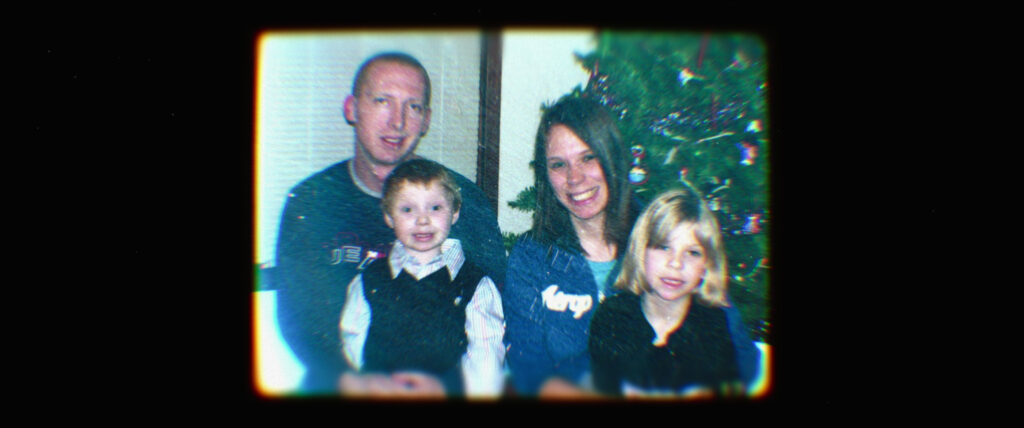

Joran van der Sloot, born in 1987 in the Netherlands, had immigrated with his family to Aruba in 1990. His father Paulus van der Sloot was a prominent attorney. His mother Anita van der Sloot was an art teacher. Joran had two younger brothers who were bullied by him, according to Lisa Pulitzer and Cole Thompson, co-authors of the 2011 non-fiction book “Portrait of Monster: Joran Van Der Sloot, a Murder in Peru, and the Natalee Holloway Mystery.” Pulitzer and Thompson, who are both interviewed in the documentary, say that long before Joran officially got into trouble with the law, he had a history of sexual harassment girls and women, as well as animal cruelty and pathological lying. At the time of Natalee’s disappearance, Joran was close to graduating from high school and had a tennis scholarship to attend St. Leo University in Florida.

That all changed on May 30, 2005, when Holloway was last seen by her friends in the early-morning hours when she left a Carlos’n Charlie’s bar in Oranjestad, Aruba. Witnesses say that she was a passenger in a car with three young men she met at the bar earlier that night: Joran and two friends: brothers Deepak Kalpoe (who was 21 at the time) and Satish Kalpoe (who was 18 at the time). Natalee had been scheduled to leave Aruba later that day but never showed up at her hotel after she was seen leaving in that car.

Over the next several weeks, all three men were arrested multiple times for suspicion over Natalee’s disappearance, but they were eventually released and were never charged because of lack of evidence. Joran’s first arrest in this case happened on the day of his high school graduation. Natalee’s divorced parents Beth Holloway and Dave Holloway were at the forefront in trying to find out what happened and get justice for Natalee. Her disappearance made the news worldwide.

Throughout the years, Joran kept changing his story about really happened the last time he saw Natalee, until he finally confessed in October 2023 that he had murdered Natalee on a beach. However, he has refused to say where her remains are. Although her body has never been found, many people had already believed for years that Natalee was dead due to foul play. (She was legally declared dead in 2012.) Several people in the documentary say that Joran’s father Paulus (who died of a heart attack in 2010) might have helped cover up the crime, or at the very least gave Joran legal advice on how to avoid being blamed for her disappearance.

On the fifth anniversary of Natalee’s disappearance (May 30, 2010), Joran murdered another beloved young woman with a promising future: 21-year-old Stefany Flores (birth name: Tatiana Flores Ramírez), who was a college student studying business. Her bludgeoned body was found in Joran’s room at the Hotel TAC, in Lima, Peru. Surveillance footage shows that she met Joran that night in a casino and went to his hotel room with him. That was the last time that anyone but the killer saw her alive.

After temporarily fleeing to Chile, Joran was arrested and extradited back to Peru, where he was convicted of this murder and sentenced to 28 years in prison. In January 2023, he was convicted of trafficking cocaine while in prison, and 18 years was added to his prison sentence. Joran is not interviewed in the documentary, and neither are his family members or any attorneys that he’s had.

Stefany’s father Ricardo Flores and her brother Enrique Flores are both interviewed in the documentary. Ricardo, who was a race car driver, describes Stephany has his constant race car companion and biggest. Ricardo says of Stephany’s death: “It’s a wound that never heals.”

A brief NBC News interview clip of Beth Holloway is shown at the end of the documentary, but she is not specifically interviewed for this movie. The interview took place after Joran’s public confession of killing Natalee. (He put the confession in writing.) Beth says in this interview clip that the pain of not knowing is worse than the pain of knowing what happened to Natalee. Matthew Holloway says that if he saw Joran in person: “I definitely want to talk to him, and I definitely want to whoop his ass. Which one will come first, I don’t know.”

The editing narrative of “Pathological: The Lies of Joran van der Sloot” goes back and forth between telling the story of Joran’s involvement in the Natalee Holloway case and the Stephany Flores case, instead of telling the story in chronological order. This is an effective way to show the disturbing parallels of how he was able to gain these women’s trust on the night that he met them and then lure them to be in a place where he could be alone with them.

Several people in the documentary say that Joran has a very charming side that masks his evil side, and he can easily fool people into thinking that he’s a “normal” person. He is also described by many people in the documentary as being a pathological liar and a gambling addict. There are other documentaries that have detailed his drug use, but this documentary doesn’t include information about Joran abusing drugs or being addicted to drugs.

Most of all, Joran has all the telltale signs of being a psychopath, say psychiatrists Abigail Marsh and Ayesha Ashai, who are interviewed in the documentary and are up front in saying that they have not evaluated Joran personally. Some of these telltale signs are his cold-blooded and methodical way in which he murdered Stephany Flores and covered up the crime; he doesn’t show empathy, remorse and the ability to take responsibility for wrongful actions that he caused; and his patholocigal lying. Even if the documentary had included an interview with Joran, he would probably tell a lot of lies in the interview.

Some of the people who were tricked by him include Beth Holloway, who were contacted by Joran in 2010, because he said he would tell them where Natalee’s body was if they paid him $250,000. The Holloways notified the FBI, which set up a sting operation for this extortion. The Holloways did not give Joran the full $250,000, but did give Joran about $30,000, which he used to go to Peru to gamble instead of going to a rehab facility in the Netherlands, which his mother had arranged for him. It was during this trip to Peru that Joran killed Stephany Flores.

John Q. Kelly, an attorney for Beth Holloway, says in the documentary he feels very guilty about his involvement in this extortion transaction that enabled Joran to traveled to Peru: “I felt I had blood on my hands.” Adding insult to injury: Until Joran was arrested for the murder, he was able to escape charges of extortion for years, because he once again recanted his statement about knowing what really happened to Natalee.

Stef Watts, a journalist who used to work for Fox News, is also interviewed in the documentary. Watts tells his story about how he was assigned to do a TV interview Joran van der Sloot in 2008, who said he would tell what happened to Natalee if he was paid $25,000. He says during the interview, Watts had to constantly remind himself that Joran was a master manipulator because Joran seemed so friendly at first, but Joran showed flashes of angry impatience over getting the money that he wanted.

After he was paid, Joran said that Natalee died from an accidental fall on a rock, and he hid her body. After the interview, he said it was all a lie, but Fox News aired the interview anyway with full disclosure that Fox News didn’t know what the truth was and had paid for an interview that Joran now says was a lie. It’s yet another example of how Joran was able to get away with something so heinous.

The most telling example of Joran’s more recent manipulations is the documentary’s interview with Eva Pacohuanaco, the Peruvian single mother who was arrested for helping Joran smuggle the cocaine that led to his conviction of drug trafficking. Pacohuanaco says that she met Joran when he was in prison for Stefany Flores’ murder, and she had an intense romance with him. At the time the interview took place, she there was a warrant for her arrest, and she was a fugitive hiding from the law.

Pacohuanaco describes meeting Joran van der Sloot at a vulnerable time in her life, after she was abandoned by the father of her son. On the day she met him she was at the prison with a friend, who was visiting another prisoner. She says she was immediately attracted to Joran because of his eyes. They began exchanging love letters soon after this meeting, and they became sexually intimate, which is allowed in the prison where he is at. She also shows her most-prized possession from the relationship: a keychain that has Joran’s name on one side and her name on the other side.

Even after finding out that Joran was in prison for murder, Pacohuanaco says of her relationship with him: “Joran was a refuge for me. Going into the prison, I felt calm, loved. He made me feel very special.” Joran told Pacohuanaco he was married but that he and his wife were getting divorced. (In 2014, Joran married a Peruvian woman named Leidy, who gave birth to their daughter. As of this writing, they are still legally married.) The documentary shows whether or not Pacohuanaco is still loyal and committed to Joran.

Other people interviewed in the documentary are Juan Callan, who is now retired but who was captain of the Peruvian National Police at the time of Joran’s 2010 arrest; Adeli Abad Marchena, the former Hotel TAC night clerk who found Stephany Flores’ body; and taxi driver brothers Williams Aparana and Oswaldo Aparana, who were unknowingly involved in driving fugitive Joran from the the Peruvian cities of Ica and Nacca, during Joran’s escape to Chile. The Aparana brothers say that Joran acted “normal” when he was their customer, and they had no idea at the time that he had just murdered someone or was running from the law.

Also interviewed are Natalee’s friends Jessica Caiola and Claire Fierman, who were with Natalee on that fateful trip in Aruba; Charles Croes, who was a liaison for Beth Holloway in Aruba; Benvinda de Sousa, a former attorney for the Holloway family; and former NBC News correspondent Michelle Kosinski, who covered the Natalee Holloway extensively during her time with NBC from 2005 to 2014. “Pathological: The Lies of Joran van der Sloot” is a no-frills and informative documentary that tells a straightforward story about many twisted lies of a murderer.

Peacock premiered “Pathological: The Lies of Joran van der Sloot” on February 27, 2024.