April 24, 2020

by Carla Hay

“Murder in the Front Row: The San Francisco Bay Area Thrash Metal Story”

Directed by Adam Dubin

Culture Representation: This documentary has a predominantly white cast (with some representation of Latinos, Asians, African Americans and Native Americans) of musicians, journalists, fans and other people discussing their memories and experiences of the 1980s thrash metal music scene in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Culture Clash: The people in this music scene had a lot of animosity toward bands and fans of “glam rock” or “hair metal” (such as Bon Jovi, Poison, Motley Crue and Ratt), whom they called “posers,” and would often get violent with these “posers.”

Culture Audience: This well-researched movie will appeal primarily to people who are nostalgic about 1980s heavy metal or people who are curious to learn more about the 1980s metal scene in the San Francisco area.

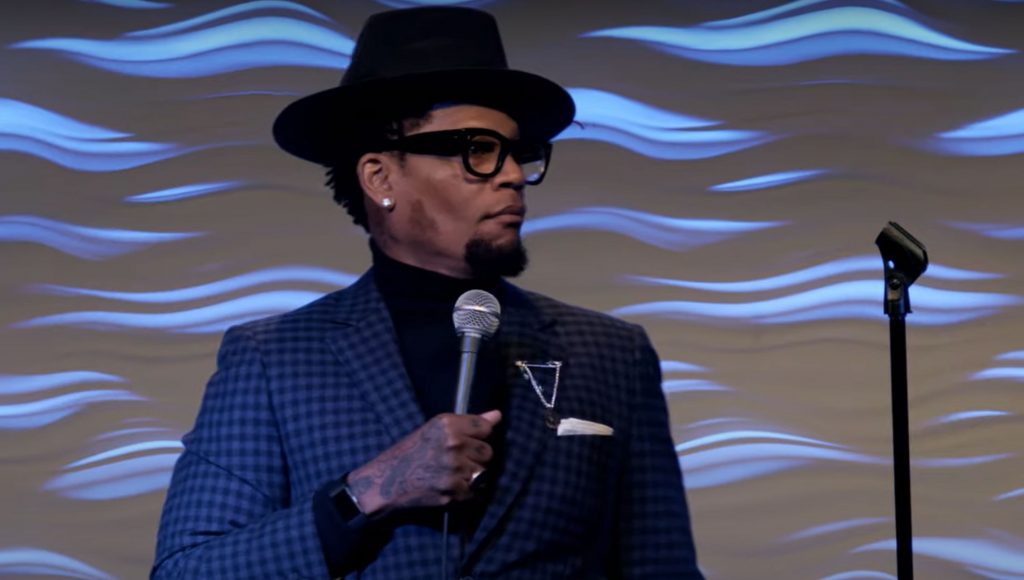

The documentary “Murder in the Front Row: The San Francisco Bay Area Thrash Metal Story” takes a comprehensive and fascinating look at this music scene that began in the early 1980s and peaked in the mid-to-late 1980s, which is the decade that gets the spotlight in this film. Several people who were part of the scene are interviewed in the movie, including members of Metallica, Exodus, Testament, Death Angel and Vio-lence, as well as journalists, fans and other assorted scenesters. Because the movie (directed by Adam Dubin and narrated by Brian Posehn) is heavy on 1980s nostalgia from people who were in their teens and 20s back in the ’80s, expect to see a lot of middle-aged people in the documentary talking about their youth.

Metallica and Exodus are presented as the most influential bands that came from the scene, so their histories get the most screen time in the movie. All four current members of Metallica are interviewed: lead singer/rhythm guitarist James Hetfield, lead guitarist Kirk Hammett, drummer Lars Ulrich and bassist Robert Trujillo, who is the only member of Metallica who wasn’t in the band in the 1980s. Exodus members who are interviewed are guitarist Gary Holt, former guitarist Rick Hunolt and drummer Tom Hunting.

Hammett was in Exodus before he joined Metallica, who fired guitarist Dave Mustaine in 1983 and replaced him with Hammett before recording the band’s 1983 debut album “Kill ‘Em All.” Mustaine went on to form Megadeth (a Los Angeles-based band) with bassist Dave Ellefson, and they are both interviewed in the documentary.

Exodus didn’t become as famous as Metallica, but Exodus is described as being a San Francisco Bay Area band that stayed true to its thrash-metal roots, since Exodus never recorded any ballads. (Thrash metal is defined as music that’s played louder and faster than regular heavy metal, with lyrics that often express anger and despair.) Another major difference between Exodus and Metallica is that Exodus has disbanded more than once, and the band’s original lead singer died. Exodus vocalist Paul Baloff passed away after having a stroke in 2012. In a touching scene in the documentary, Holt and Hunting are shown visiting Baloff’s grave.

The documentary gets its name from the nonfiction book of the same title written by Harald Oimoen and Brian Lew, who are both interviewed in the film. And the book’s “Murder in the Front Row” title came from a line in the title track of Exodus’ 1985 debut album “Born in Blood,” which was inspired by all the blood and violence that would occur at many of these bands’ nightclub shows.

The targets of this violence were usually “posers”—the derogatory name given to fans of ’80s “glam rock” or “hair metal” bands, such as Poison, Ratt, Motley Crue and Bon Jovi. Several people in the documentary describe how bands and fans of thrash metal would often immediately pick fights with “posers.” And with or without any “posers” around, there would be violence, whether it was getting slammed in mosh pits, throwing glass bottles, getting into fist fights, or destroying walls and furniture.

Baloff was notorious for starting many of these fights, especially when he was on stage. Exodus had a specific posse of fans known as the Slay Team that would be ready to get rough with “posers.” And there was even an underground Slay Team comic book illustrated by Elizabeth “Lizzie” Francois, who was Baloff’s girlfriend at the time. She’s interviewed in this movie, and some of the comic book illustrations are shown.

Even with all of this violence, the people interviewed in the movie look back on what they experienced with a lot of fondness. (“The [mosh] pits were violent as hell. It was glorious,” says Death Angel’s Mark Osegueda.) The violence is described as not so extreme that anyone got murdered at concerts, but there was enough bloodshed and broken bones for it to be dangerous to go to many of these male-dominated shows. Hammett describes how the musicians often dealt with it: “The anger and frustration [were] being channeled into our instruments.”

The trash-metal scene in the San Francisco Bay Area was largely centered in working-class areas of the East Bay, where in the late 1970s and early 1980s, unemployment and crime rates were high. Oakland and Berkeley are the two biggest cities in the East Bay, with Oakland known for its racially diverse mix of people, and Berkeley having an image as a hippie-friendly, liberal college hub. Kids were starting to discover new heavy metal, which was thriving in Europe, by trading tapes and reading about bands in magazines. Kerrang! (a British magazine for heavy metal) had free ads for pen pals, while Metal Mania had gone from being a newsletter to being an underground magazine by 1981.

Hammett remembers that in the mid-to-late 1970s, when he was a teenager in the working-class California suburbs of El Sobrante and Richmond, “We were far away from the city. We were isolated. There was nothing to do.” He adds, “There was something I wasn’t getting enough of until I heard this band called UFO.”

Hammett says he became obsessed with UFO and found other passionate fans of UFO with Lew, Rich Quintana (a journalist and DJ at college radio station KUSF) and Rich Burch, who died of needle-related AIDS in 1993. Exodus guitarist Holt describes Hammett as his musical mentor and “the first guy to play me Uli Roth-era Scorpions.”

Around the same time that the thrash-metal scene was growing in the Bay Area, San Francisco retailer Record Vault (which had a lot of imported music that bigger stores wouldn’t have) and a nightclub in Berkeley called Ruthie’s Inn became important hangouts. Ruthie’s Inn is described as the “epicenter” of the scene, because it’s where all the thrash bands that mattered ended up playing at one time or another.

The owner of Ruthie’s Inn was someone who was not a typical rock promoter—he was an African American named Wes Robinson, who had a background in blues music. Robinson’s daughter Darelle S. Ali explains in the documentary why her late father was so open to booking thrash music at Ruthie’s Inn: “His joy for something led his actions in getting involved with it. He never got involved with something just because he thought he’d be able to get involved with it.”

The history of Metallica has been covered numerous times elsewhere. Therefore, people who are already familiar with the band’s 1980s background won’t find out anything new from watching this documentary. Metallica was originally based in Los Angeles, but original band members Hetfield and Ulrich (a Danish immigrant) said that they didn’t really fit in with the Los Angeles rock scene, which was was mostly about punk acts or “heartthrob” metal bands when Metallica formed in 1981.

Metallica found instant acceptance when the band played in the San Francisco Bay Area. And when Metallica needed a new bassist to replace Ron McGovney in 1982, Metallica recruited Cliff Burton from the band Trauma. Burton only agreed to join Metallica if the band relocated from Los Angeles to his home base of the San Francisco Bay Area. Burton tragically died in a tour-bus accident in 1986, at the age of 24. Corinne Lynn (Burton’s girlfriend at the time) and his father Ray Burton are interviewed in the documentary.

Although the documentary is about the San Francisco Bay Area thrash scene, metal bands from other parts of the U.S. are interviewed in the movie if they were part of Metallica’s and Exodus’ 1980s history and if they had a large fan base in the Bay Area. Anthrax drummer Charlie Benante is interviewed because Anthrax (from New York City) and Metallica were signed to Metal Blade Records early in their careers, and the two bands toured together. Metal Blade was based in Old Bridge, New Jersey, where Metallica stayed when recording “Kill ‘Em All.” While in Old Bridge, Metallica developed a fan base called the Old Bridge Militia, who often partied with the band at a place they named their “Fun House.”

Slayer, a Los Angeles-based band, is also featured in the documentary, because Exodus guitarist Holt ended up joining the Slayer in 2011 and was in the group until Slayer disbanded in 2019. Slayer’s longtime drummer Dave Lombardo says of the Bay Area thrash scene in the 1980s: “We felt at home there” because Los Angeles was saturated with glam rock at the time.

Slayer guitarist Kerry King adds, “The Bay Area crowds were far more advanced” than the audiences in Southern California. Slayer lead singer/bassist Tom Araya sheepishly remembers how Slayer used to be a band that wore heavy eyeliner makeup, until thrash musicians in the Bay Area convinced them to stop wearing makeup before Slayer played at Ruthie’s Inn. It was a pivotal show because it was the first one that Slayer did without makeup.

Several people in the documentary also talk about the wild parties that were part of the scene. The so-called Metallica Mansion or MetalliMansion (a modest house in El Cerrito) was a big party hangout, although members of Exodus say that Metallica was hardly there because the band was usually away on tour. Hetfield describes it as a “total bachelor pad” where no area was safe from some of the mayhem that could take place there.

On a more sobering note, Hetfield also remembers famous San Francisco music promoter Bill Graham lecturing him early in Metallica’s career about the band’s wild ways, which included trashing dressing rooms. (Graham died in a helicopter crash in 1991.) Hetfield says that the talk had a big impact on him, because Graham said he had a similar talk with Keith Moon (The Who drummer) and Sid Vicious (of Sex Pistols fame), who both died of drug overdoses in the late 1970s.

Hetfield says that he was so remorseful about the violent damage in the dressing room that he offered to pay for the cost. But he noticed that the next time Metallica played a Bill Graham show, the entire dressing room was covered with plastic protectors. Metallica’s performance at the 1985 Day on the Green festival in Oakland (a Bill Graham Presents show) is mentioned as a major turning point for the band’s increasing popularity.

A counterpoint to Day on the Green was Day in the Dirt, a thrash-metal festival in Berkeley that was promoted by Ruthie’s Inn owner Robinson. The first Day in the Dirt in 1984 had a lineup that included Slayer, Exodus, Suicidal Tendencies and Possessed. Speaking of Possessed, bass player Larry LaLonde (who was an underage teen in high school when he joined the band and would later find fame as a member of Primus) says that most of the satanic imagery by the thrash bands back then was just created to get attention and that none of the band members took it seriously.

The late Debbie Abono, who used to be the manager of Possessed and Exodus, is fondly remembered by several people in the documentary. Metallica’s Hetfield says that she was Metallica’s “metal mom” and that her house in Pinole “was always a safe place,” even though her daughter Julie Ebding laughs when she remembers some of the crazy things she would have to walk over in the house when she had to go to school in the morning. LaLonde gives a lot of credit to Abono for his early music career, and he mentions that she paid for the guitar lessons that LaLonde got from Joe Satriani. Abono’s daughter Nancy Labowitz and Rick Nelson-Abono are also interviewed in the documentary.

Other people interviewed in the movie include Chuck Billy and Alex Skolnick of Testament; Phil Demmell and Robb Flynn of Vio-lence; Metallica fan club leader K.J. Doughton; Metal Blade Records co-founder Brian Slagel; Metallica road crew member John Marshall; Bay Area scenester Sven Soderlund; former Faith No More guitarist Jim Martin, who was in EZ-Street, Cliff Burton’s first band; Mark Menghi of Metal Allegiance; Toni Isabella of Bill Graham Presents; music journalists Alex Gernand, Steffan Chirazi and Joel Selvin; and fans Connie Taylor and Pam Behrhorst, who remember racking up expenses on Metallica’s checking account, and Taylor’s parents paying the cost to replace the money before the band found out.

Despite this long list of people interviewed in the movie, “Murder in the Front Row” doesn’t feel overstuffed with talking heads. That’s because this well-edited film keeps things lively with great stories and a treasure trove of archival concert footage and photos. People who despise heavy metal probably won’t enjoy this movie. But for everyone else, it’s a fun ride back to an era when musicians and fans were allowed to be a lot more hedonistic, and heavy metal was celebrated a lot more than it is now.

MVD Visual released “Murder in the Front Row: The San Francisco Bay Area Trash Metal Story” on digital, VOD and DVD on April 24, 2020. The DVD has an extra 90 minutes of bonus footage.