May 19, 2021

by Carla Hay

“Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street”

Directed by Marilyn Agrelo

Culture Representation: The documentary “Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street” features a predominantly white group of people (with some African American and Latinos) discussing their connection to the groundbreaking children’s TV series “Sesame Street.“

Culture Clash: “Sesame Street,” which launched in 1969 on PBS, was the first nationally televised children’s program in the U.S. to be racially integrated, and some TV stations initially refused to carry the show because of this racial diversity.

Culture Audience: “Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in the history of “Sesame Street” from 1969 to the early 1990s.

“Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street”(directed by Marilyn Agrelo) is a documentary that is very much an “origin story” of “Sesame Street,” because it focuses so much on what the show was like in the 20th century. The movie gives a very good and comprehensive overview of the behind-the-scenes work and conflicts that went into making this groundbreaking children’s show, which has been televised in the U.S. on PBS since 1969. (“Sesame Street,” which is filmed in New York City, began airing first-run episodes on HBO in 2016, and then on HBO Max in 2020.) What’s missing from the documentary is more current information about “Sesame Street,” including muppet characters that were introduced in the 21st century, and a contemporary context of why the show is still impactful today.

The ABC documentary “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” takes a more modern look at the “Sesame Street” phenomenon and how the show has adapted to a global audience and a more diverse culture. “Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street” is pure nostalgia for a bygone era when the Internet didn’t exist, and kids’ on-screen entertainment options at home were mainly to be found on television, until computers and video games became household items in the 1980s. “Street Gang” (which was produced in association with HBO Documentary Films) is inspired by Michael Davis’ 2008 non-fiction book “Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street.”

“Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street” is so rooted in the past that it’s impossible not to notice a huge racial disparity between who appeared on camera for “Sesame Street” and who was running the show behind the scenes. In “Street Gang,” several of the original “Sesame Street” staffers say that the show was conceived to have a target audience of “inner city” African American children, with cast members who were African American, white and Hispanic. Later, a few Asian cast members were added.

But for the longest time, the only people making decisions about the show were white. The head writers and executive producers were white, almost all the puppeteers were white, and even the crew (camera operators, editors, etc.) were all white. It’s all there to see in the archival footage.

And it’s a sign of the times. When “Sesame Street” was launched in 1969, it was only five years after the Civil Right Acts went into law, and much of the United States was still unofficially racially segegrated. Therefore, the racially integrated cast for “Sesame Street” was very groundbreaking for a children’s show at the time.

The show’s setting also broke traditions in children’s television: It took place in an imaginary urban location called Sesame Street, where humans and a variety of puppets (also known as muppets) co-existed and learned from each other. Almost everyone agrees that the muppets were the real stars of the show.

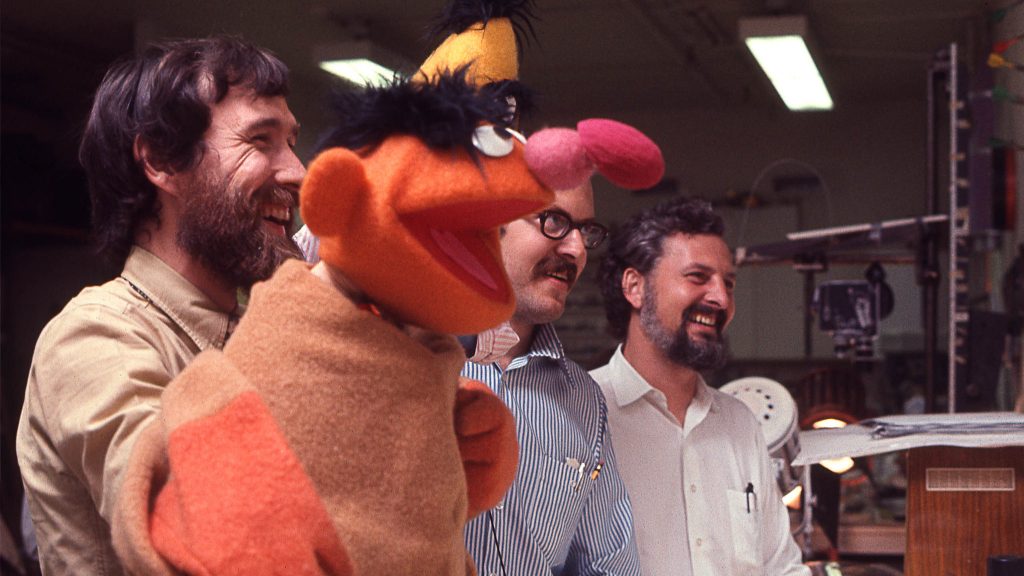

“Sesame Street” puppeteers/writers Jim Henson and Frank Oz, who both created and voiced several muppet characters (including best friends Ernie and Bert), get a lot of praise in the documentary for being the show’s driving creative force. Joan Ganz Cooney and Children’s Television Workshop co-founder Lloyd Morrisett are credited with coming up with the “Sesame Street” concept, with Ganz Cooney being largely responsible for putting together the show’s original team. And longtime “Sesame Street” director/writer Jon Stone (who died in 1997, at age 64) is singled out as having the most to do with keeping the show’s proverbial engine running for decades. Henson died in 1990, at age 53. Oz did not participate in the “Street Gang” documentary.

Ganz Cooney explains in “Street Gang” why it was so important to her for “Sesame Street” to be racially integrated, at least on screen. She says that she was “heavily involved in the civil rights movement. I was not focused on children though.” That changed when Morrisett attended a dinner party hosted by Ganz Cooney in the late 1960s.

Morrisett remembers, “I was a psychologist at the Carnegie Foundation, and we were heavily influenced by the national dialogue in the [racial and economic] gap that was being created in schools. I wondered if there was a possibility for television to help children with school, but television was not very popular with the Carnegie staff. Academics weren’t interested in television.'”

At this fateful dinner party, Morrisett asked Ganz Gooney if television could be used as a way to educate children. The Carnegie Foundation then hired Ganz Cooney to do a feasibility study, where the bulk of the study’s original $8 million budget came from the U.S. federal government’s Office of Education. The study revealed that because children were spending more time watching TV than children did in the 1950s, and because more children than ever before had mothers working outside the home, television had become an electronic babysitter for a lot of kids.

And so, the idea of “Sesame Street” was born to be a show that would both entertain and educate pre-school-age children, in a racially integrated setting that had puppets with distinctive personalities. And, for the first time in American TV history, television writers and children’s educators would collaborate on episodes. At first, the idea was to have the humans in episode segments that were separate from the muppets. But test screenings shown to kids found that the kids responded best to the show when the humans interacted with the muppets.

Ganz Cooney says in “Street Gang” that even though she came up with the concept of “Sesame Street,” she experienced sexism from certain people who didn’t think a woman should oversee the show. However, Ganz Cooney says that because the entire show “was all in my head,” TV executives needed her to bring her vision to reality. They had no choice but to give her the top leadership role for “Sesame Street.”

One of the first people she recruited was Sharon Lerner, who had a master’s degree in education from Columbia University. Lerner was hired to be a research and curriculum coordinator for “Sesame Street.” Lerner says it was “unprecedented” to see educators and TV writers teaming up to help create a TV show for children. Other staffers from the early years of “Sesame Street” who are interviewed in the documentary include camera operator Frank Biondo and composer/lyricist/writer Christopher Cerf.

Based on the research studies, economically disadvantaged non-white children in urban areas, especially African American children, were getting inferior educations in public schools, compared to their white counterparts. And so, the idea was to target these “inner city” kids with a TV show that could help bridge the gap in their education. In an archival TV interview, Stone describes why an urban street was chosen as the “Sesame Street” setting: “To the 3-year-old cooped up in the room upstairs, the action is on the street.”

Ganz Cooney admits that at first she wasn’t convinced that the show should take place on an urban street because “I didn’t know how it would play to suburban parents.” Translation: “I didn’t know if it would alienate white people who live in very white neighborhoods.” Jon Stone is given credit for the urban street idea, which turned out to be the right concept, because “Sesame Street” soon developed a reputation for not shying away from real-life topics that are often tough to discuss with kids, such as death, bullying and loneliness.

In “Street Gang,” Ganz Cooney says she enlisted the help of an African American consultant named Evelyn Davis to do outreach work in African American communities before “Sesame Street” was launched. Although having this inclusivity was certainly necessary and thoughtful, it’s clear that in those early “Sesame Street” years, the decision makers at “Sesame Street” didn’t want African American input to include hiring any African Americans in leadership positions for the show.

The closest that “Sesame Street” had to an African American creative executive in the show’s early years was Matt Robinson, who was the first actor to portray the character of Gordon, and he was a writer on the show. Robinson (who died in 2002, at the age of 65) came from a TV background of hosting, writing and producing. Before joining “Sesame Street,” he was the host of the Philadelphia talk shows “Opportunity in Philadelphia” and “Blackbook.” In addition to portraying Gordon on “Sesame Street,” he created and voiced the show’s first African American muppet character: Roosevelt Franklin, which was on “Sesame Street” from 1970 to 1975.

Dolores Robinson, Matt Robinson’s widow, remembers her late husband’s contributions to “Sesame Street” as being part of the era when the Black Power movement was blossoming. “These were revolutionary times,” she says. Matt and Delores’ children Holly Robinson Peete and Matt Robinson Jr. have different perspectives, since they were in “Sesame Street’s” target age group when their father was on the show.

Robinson Peete says, “Back then, if your dad was Gordon on ‘Sesame Street,’ that was a big deal.” Matt Robinson Jr. adds, “We looked at the TV, and it still wasn’t registering, like, how did he get in the [TV] box?” Dolores Robinson says of the Roosevelt Franklin character, “For Matt, Roosevelt Franklin represented truth.”

The documentary mentions that the Roosevelt Franklin character wasn’t well-received by many African American parents and educators, who felt that Roosevelt Franklin represented too much of the negative “ghetto” stereotype used by racist people who think black people are inferior. “Sesame Street” got enough complaints about Roosevelt Franklin that the character was removed from the show in 1975, without any explanation to the audience. Matt Robinson stopped doing the Gordon character in 1972, but had stayed on with the show behind the scenes as a writer and to voice the Roosevelt Franklin character. The removal of the Roosevelt Franklin character was apparently one of the last straws for Matt Robinson, and he exited “Sesame Street” in 1975.

After Matt Robinson stopped portraying the character of Gordon, Hal Miller stepped into the role from 1972 to 1974. Miller was replaced by Roscoe Orman in 1974, who has been doing the role of Gordon ever since. Orman says of “Sesame Street” writer/director Jon Stone’s contributions to the show: “Jon was the guy who really created the reality of it—the style, the vision of the show.”

Sonia Manzano, who portrayed the role of Maria on “Sesame Street,” comments on Stone: There were a lot of shows that really talked down to kids. And he didn’t really want that. Jon Stone thought that you could have a kids’ show where adults wouldn’t run for the door as soon as it’s on.” Manzano also recalls that Stone didn’t want her to wear too much makeup on the show, because he wanted Maria to look like a real person, “raw and unpolished.”

Manzano and Emilio Delgado (who portrayed Maria’s boyfriend-tuned-husband Luis) talk about the importance of Hispanic representation on “Sesame Street.” Delgado says that as an actor, “Sesame Street” was the first show in a long time where he wasn’t cast as a criminal or a menial servant, and he was grateful for doing a character that wasn’t about those stereotypes. He says of the Luis character: “He was a regular person! He was part of the neighborhood and he had a business.”

During the first season of “Sesame Street,” the cast members did a 1969 U.S. tour with the muppets and life-sized characters from the show. It was a big success. Bob McGrath, who portrayed the character of Bob on the show, remembers the tour this way: “It was a madhouse.” He gushes about his “Sesame Street” experience: “It was a dream come true to fall into this job.” Ganz Cooney comments on “Sesame Street’s” instant popularity: “I was stunned by the overwhelming support for what we were doing. It was if the world had been waiting for us.”

Well, not everyone was so welcoming. The documentary mentions that certain TV network executives in Mississippi were so outraged about “Sesame Street” having a racially integrated cast that these executives refused to televise the show on their local PBS affiliates for a brief period in 1970. In archival news footage, one of these TV executives (who is unidentified in the footage) denied that the decision was racist and blamed it on community standards. Apparently, these “community standards” were offended by a children’s show with people of different races getting along with each other.

Bob McRaney, the general manager of the NBC affiliate WJDX-WLBT in Jackson, Mississippi, broke away from this racist mindset and decided to televise “Sesame Street” anyway. “Sesame Street” got such great ratings for WJDX-WLBT that eventually all the racist TV executives who thought their communities would be ruined if they saw “Sesame Street” suddenly changed their minds and wanted “Sesame Street” on their TV stations. Sometimes greed trumps racism.

Behind the scenes of “Sesame Street,” things weren’t as harmonious as they were presented on screen. Ganz Cooney says that she and Stone clashed with each other. In the documentary, she implies that he might have been envious that she got most of the attention for “Sesame Street’s” success. Ganz Cooney describes Stone as “a very sensitive, difficult man.”

Stone’s daughter Kate Stone Lucas says that her father “battled depression all of his life … ‘Sesame Street’ was the love of his life.” Stone Lucas and her sister Polly Stone say that their father, whom they describe as a civil rights activist, initially wasn’t sold on the idea of doing a children’s TV show because he had become disillusioned with television at that point in his career. Stone Lucas says what convinced him to be involved in “Sesame Street” was Ganz Cooney’s “political vision” to improve the quality of children’s TV, especially for inner city kids whose parents were working while the kids were at home.

Stone Lucas says her father’s personality was that he “saw the world in black and white … You were either a good guy or a bad guy.” He was an iconoclast at heart who resisted being too corporate. One of the anecdotes mentioned in the documentary is that there was an office “push pin” bulletin board that had the words “Children’s Television Workshop,” and Jon Stone would rearrange the letters so that they would spell “Children’s Porkshow.”

The documentary doesn’t have much screen time that gives insight into the creation of the most iconic muppets, such as Kermit the Frog (originally voiced by Henson), Grover (originally voiced by Oz), Cookie Monster (originally voiced by Oz), Ernie (originally voiced by Henson), Bert (originally voiced by Oz), Oscar The Grouch (originally voiced by Caroll Spinney) and The Count (originally voiced by “Sesame Street” head writer Norman Stiles, who is one of the people interviewed in “Street Gang”). “Sesame Street” puppeteer Fran Brill says of Henson and Oz: “Jim and Frank were a comedy team … The dynamic between these two guys was magic.”

Off screen, Henson and Oz were described as opposites who weren’t really friends, but they worked well enough together that they had a special chemistry that translated well on screen. Ironically, Henson’s workaholic ways in children’s entertainment (he was also a key creator of “The Muppet Show”) meant that he didn’t spend as much time with his kids as other fathers did. Jim Henson’s children Lisa Henson and Brian Henson are interviewed in “Street Gang.”

Brian Henson says that it was normal for him as a child to not see his father for three or four days in a row because his father was so busy working. He also says, “My father was a pretty quiet, shy person, but he wanted to be hip. He wanted to be cool. And he wanted his company Muppets Inc. to have a very cool reputation. Children’s entertainment wasn’t what he had in mind.”

Ganz Cooney remembers the first time she saw Henson in a staff meeting, she thought he looked like a hippie and she wasn’t sure how he would fit in with the more conservative-looking employees. But she says that Henson became one of her favorite “Sesame Street” people. “He was terrific,” she says adoringly. The documentary has some archival clips of Henson and Oz, separately and together, behind the scenes and doing interviews.

Spinney (who died in 2019, at age 85) was famously the man inside the Big Bird costume, and he was interviewed for this documentary, which has footage of him with his Oscar the Grouch puppet during the interview. Big Bird was originally conceived as a klutzy character with the intelligence of a teenager or young adult. But it wasn’t long before the character of Big Bird was changed to have the innocence of a child in “Sesame Street’s” target age group of 3 to 5 years old.

In 1982, the real-life death of actor Will Lee, who played Mr. Hooper on “Sesame Street,” was written into the show as Mr. Hooper dying off-camera. Big Bird’s denial about the death was one of the more memorable aspects of this tearjerking episode. In the documentary, “Sesame Street” people who were involved in this episode say that they wanted to keep the show honest by not lying to the audience about why Mr. Hooper wasn’t coming back to “Sesame Street.”

Music has always been a big part of “Sesame Street,” which features the human characters and muppets performing original songs and cover tunes. Joe Raposo, who composed the “Sesame Street” theme song and many other tunes for the show, is fondly remembered as a larger-than-life character. His son Nick Raposo says that his father didn’t want to talk down to children in his songs.

Kermit the Frog’s melancholy “It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green” is mentioned as a song that could be interpreted as a metaphor about racism. The documentary also includes clips from several music stars who made guest appearances on “Sesame Street,” including Stevie Wonder, Johnny Cash, Paul Simon and Odetta Holmes. There’s also footage of Jesse Jackson’s well-known “Sesame Street” appearance where he leads a group of kids in a pep talk chant that starts off with repeating “I am somebody!”

“Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street” certainly has plenty of heartwarming moments. The movie also has many good anecdotes and archival footage. But the documentary is very American-centric because it doesn’t really acknowledge the impact that “Sesame Street” has had worldwide. If you believed everything that’s presented this documentary, Americans are the only people worth interviewing about a global show such as “Sesame Street.” (“Sesame Street” is currently available in about 150 countries.)

And the “Street Gang” filmmakers didn’t seem to bother asking Ganz Cooney or any of the other white people from the original “Sesame Street” executive team why a show that they wanted to be aimed at urban African American kids had no African Americans making major decisions about the show in its early years. The documentary doesn’t seem to want to acknowledge that the groundbreaking racial integration on “Sesame Street” was just in front of the camera only. Behind the camera, it seems that the hiring practices for the “Sesame Street” original production team weren’t reflective of progessive civil rights after all, even though these are the same people who claim to be passionate about civil rights and racial equality.

“Sesame Street” has a long history, and this documentary’s real focus is what “Sesame Street” did up until the 1990s, when Jim Henson and Jon Stone died. Therefore, the “Street Gang” movie will probably be best enjoyed by people who are old enough to remember “Sesame Street” before the 1990s. It’s a meaningful nostalgia trip for “Sesame Street” fans, but not a completely thorough one for people who want more of “Sesame Street’s” history after the 1990s.

Screen Media Films released “Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street” in select U.S. cinemas on April 23, 2021, and on digital and VOD on May 7, 2021. The movie’s release date on Blu-ray and DVD is July 6, 2021. HBO and HBO Max will premiere the movie on December 13, 2021.