February 19, 2020

by Carla Hay

“Banksy and the Rise of Outlaw Art”

Directed by Elio España

Culture Representation: This male-centric documentary explores the history of graffiti and other street art in the United States and Europe, with a particular focus on British artist Banksy, who has kept his real identity anonymous to the public while experiencing worldwide fame.

Culture Clash: The artists often break the law, and there are constant conflicts over how much commercialism and mainstream acceptance that artists can and should achieve.

Culture Audience: “Banksy and the Rise of Underground Art” will appeal mostly to people interested in street art and the artists who’ve made their mark on pop culture.

The intriguing documentary “Banksy and the Rise of Outlaw Art” (written and directed by Elio España) begins with what is perhaps the most famous stunt ever pulled by the mysterious artist who calls himself Banksy: At a Sotheby’s auction in 2018, after Banksy’s painting “Girl With a Balloon” sold for more than £1 million, the picture in the frame descended from the frame and began to be shredded, as if the frame had been activated to become a shredder. As the stunned audience looked on, it became apparent that the sale of the painting was yet another one of Banksy’s notorious pranks, and it became a viral moment on the Internet. Instead of the shredded picture being devalued, the price of “Girl With a Balloon” more than doubled after the shredding.

This stunt is a microcosm of the uneasy relationship that street artists have with mainstream acceptance and commercialism. Many artists want to have an aura of being underground and “edgy,” but at the same time they want recognition, and being too underground doesn’t get the type of recognition that many artists want. And then there’s the matter of being able to make a living from art. How popular does an artist have to get before the artist is considered “uncool” or a “sellout”?

It’s a tricky dilemma that Banksy has faced since he emerged in the art scene in Bristol, England, in the early 2000s. He’s famous for his mystique—he refuses to reveal his true identity, although there are plenty of theories about who he really is—but at the same time, he courts worldwide attention with his publicity stunts. Banksy started out as a graffiti artist, and then helped make stenciling art “cool” again to buy for mainstream audiences, before expanding to bigger art platforms and elaborate performance-art installations.

Although Banksy is the main focus of this documentary (which is narrated by British actor Mark Holgate), the movie also takes a look at the origins of modern street art that began in the late 1960s with the graffiti movements in Philadelphia and New York City. By the late 1970s, graffiti was the leading form of street art in big cities, particularly in the United States and Europe, where the artists (who were almost always young people) had easy access to numerous cans of spray paint. According to the unwritten code of graffiti artists, the cans of paint that they used had to be stolen—the more stolen paint cans, the better. And in order to avoid detection, graffiti artists almost never used their real names, since most of their work was considered illegal vandalism.

The rise of hip-hop was tied in to graffiti art, which peaked in the 1980s. Tony Silver’s 1983 documentary “Style Wars” and Henry Chalfant and Martha Cooper’s 1984 book “Subway Art” were also hugely influential for countless graffiti artists and other street artists. Banksy came of age when graffiti art was at its peak. The most basic form of this art is a “tag” (a name scrawled on something), while a “piece” is a more elaborate form of graffiti art, such as a mural.

In New York City, street artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring became known to the mainstream and took graffiti art to a whole different level in pop culture. Unlike many artists who used aliases to remain anonymous, Basquiat and Haring used their real names and became famous beyond the art world, as they appeared in TV shows and had a lot of other media coverage. (And as is the case with most famous artists, their work increased in value after their untimely deaths.) It was that level of mainstream fame that many graffiti artists went to great lengths to avoid, but Banksy is the rare artist who’s been able to straddle both contradictory worlds of anonymity and fame.

A considerable chunk of the documentary covers the history of graffiti in England, particularly in Banksy’s work-class hometown of Bristol. (Banksy’s “The Mild Mild West” piece is considered an unofficial “welcome sign” in Bristol.) Whereas hip-hop was the home-grown soundtrack of American graffiti artists and became a worldwide phenomenon in the 1980s, the British music scene that heavily influenced graffiti artists included the Wild Bunch collective of DJs and rappers, which included Massive Attack and Nellee Hooper. (Massive Attack member 3D is widely considered one the U.K.’s first well-known graffiti artist.) Later, in the 1990s, house music and rave culture became closely associated with street artists, particularly those in Great Britain.

The Barton Hill area of Bristol was one of the few places in England where graffiti was legal, so it became a haven for graffiti artists such as Banksy, Inky, Felix and Chaos. One of the key figures in the Bristol graffiti scene was artist John Nation, who was one of the leaders of the Barton Hill Youth Centre during this era. In the documentary, Nation says that when he first got involved in the Barton Hill Youth Centre, it was mostly a place for the “white working-class” who were “hostile to outsiders, into football hooliganism and the right-wing National Front.” After graffiti culture became more influential in the neighborhood, the youth center began to see a different kind of rebellious youth—ones that were more artistic and open-minded.

But what some people consider to be graffiti art, many others see as vandalism. Police and other government officials began cracking down on graffiti in the late 1980s. In 1989, the British Transport Police launched Operation Anderson, the biggest anti-graffiti operation in U.K. history. Several graffiti artists in the Bristol area were arrested, but Barton Hill Youth Centre’s Nation refused to snitch and reveal the identities of more graffiti artists for police to arrest. Because he refused to cooperate with police by naming names, Nation was jailed for conspiracy. The documentary singles him out as an unsung hero who helped change the course of graffiti art in England because he prevented a lot of artists from being arrested.

In 1994, John Major, who was the United Kingdom’s Prime Minister at the time, launched the Criminal Justice and Order Act, which cracked down on raves but also racially targeted gypsies and other members of traveling communities. The Criminal Justice and Order Act further clamped down on graffiti art, which had been on a decline. That led in part to Banksy and other street artists to transition more into doing stenciled art and more art installations. (French graffiti artist Blek le Rat is cited as Banksy’s biggest influence in stencil art.)

The 1990s were also the decade of the rise of the Young British Artists, most of whom were centered in London and unabashedly embraced commercialism. In the art world, this was exemplified by Damien Hirst, who went from being an underground artist to being firmly entrenched in the upper echelons of high-priced fine art. The documentary points out that Hirst is the kind of artist who’s the antithesis of what street artists want to become. Street artists who want to maintain their artistic credibility among their peers go to great lengths to make their art affordable and accessible.

Not surprisingly, Banksy is not interviewed for this documentary. However, the movie does have a rare clip from the 1995 BBC documentary “Shadow People” that interviewed Banksy in 1993, very early in his career. (In the interview, he covered his lower face with a scarf in the interview, but his eyes, hair and voice are not hidden.) “Banksy and the Rise of Underground Art” also has an actor narrate excerpts of some print-media interviews that Banksy has done over the years.

“Banksy and the Rise of Underground Art” doesn’t have any new interviews with Banksy, but the film does interview several people who know him very well. They include art promoter/photographer/curator Steve Lazarides (who’s worked with Banksy since 1997) and artist Ben Eine, who’s collaborated with Banksy on many projects, including the annual Santa’s Ghetto Party (launched in 2002) and one of Banky’s most famous projects: painting murals on the West Bank wall in Palestine in 2005.

In the documentary, Eine remembers that the biggest challenge for the West Bank murals wasn’t avoiding arrest by the soldiers who were guarding the wall but it was getting all the equipment there (ladders, paint, etc.) in the first place. When they were stopped by customs agents or other security people, the artists were able to get past them by saying that they were there for educational purposes. (And the artists did do some mentoring to local youth.) Eine says that the soldiers at the wall weren’t as difficult as people might think because if any soldiers stopped what the artists were doing and told them to leave, the artists would just move to another section of the wall, out of sight from the soldiers, and repeat the pattern until they were caught again.

The documentary interviews other artists, such as Scape Martinez, Risk and Felix “Flx” Braun. And there’s mention of how Banksy’s unorthodox path to art stardom paved the way for other underground street artists who became mainstream too, such as Shepard Fairey, OSGEMEOS, Swoon, RETNA and Invader. In London, the Shoreditch area became a hot spot for street art, and the Dragon Bar emerged as a popular hangout for artists.

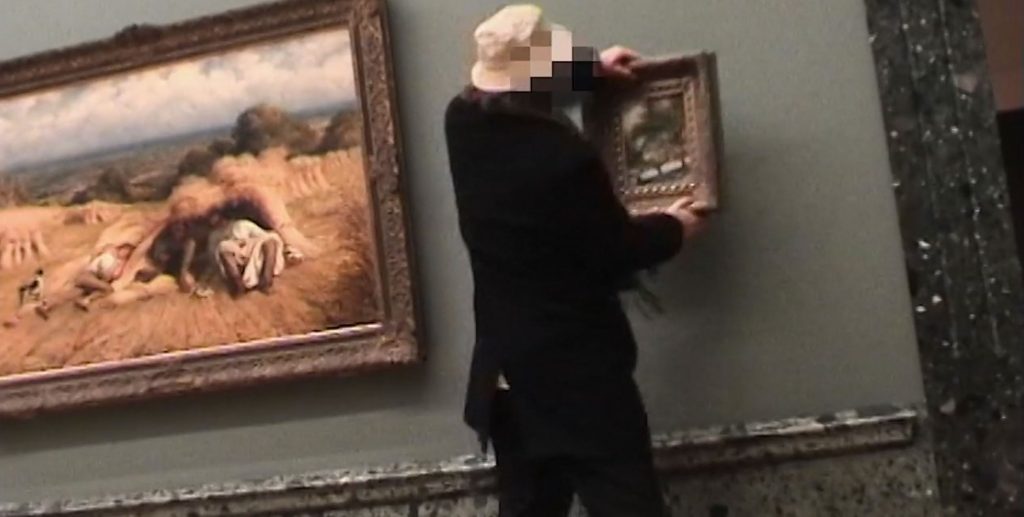

As Banksy gained more notoriety, so too did the size of his art installations and pranks. His breakthrough art installation was 2003’s “Turf War,” which included live cows that were painted with animal-safe paint. In the mid-2000s, he began secretly (and illegally) putting up his own art at famous art museums around the world, including the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The documentary includes video footage of Banksy committing this act with his face blurred out—a clear indication that Banksy had at least one accomplice with a video camera ready to record him in the act and release the footage.

He also didn’t forget his Bristol roots. In 2009, his art legitimately took over the Bristol museum in the “Banksy vs. Bristol Museum” exhibit,” which had several Banksy pieces displayed side-by-side with the Bristol Museum’s resident art. Many of the themes in Banksy’s art is about the entities representing the powerless and oppressed (whether they’re children, mice, monkeys or other animals) rising up, taking over and/or outsmarting those in power.

And Banksy went further than showing his art in museums and galleries. His Dismaland art installation (at the seaside resort town of Weston-super-Mare in Somerset, England) was a social commentary on what Disneyland would look like if it were taken over by cynical people with a dark outlook on life. In 2017, he created the Walled Off Hotel, built alongside the Israeli West Bank barrier in Bethelem, which displays a great deal of his work.

Banksy promoter Lazarides openly admits that he prices much of Banksy’s art based on how desperately people seem to want it. Lazarides says that people offer to buy the art for much larger sums than the price quote that the seller was going to give, which is why he often lets the buyers be the first one to name the price. (It’s an open secret that art dealers always use this “smoke and mirrors” technique.) And the more that art is perceived as being desired by society’s rich and famous, the more money can be charged to buy it.

When celebrities such as Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Jude Law and Christina Aguilera began attending Banksy exhibits and buying his art, naturally the prices for Banksy’s art increased dramatically. However, the documentary mentions that during one high-profile exhibit that Banksy did in Los Angeles, he sold much of his original art at a nearby anonymous street stand at cheap prices. And the art at the street stand didn’t sell very well. If the same art from the street stand had been put on display in the high-profile Banksy exhibit nearby, it would have sold for thousands more. It’s an example of how presentation, marketing and perception are the driving forces in how art is priced and sold.

“Banksy and the Rise of Outlaw Art” does a very good and comprehensive job of immersing viewers into the culture of street art and how the artists can have a love/hate relationship with the mainstream. The documentary is essential viewing not just for people who like street art but also for anyone who’s fascinated to see how this part of culture is dealing with the age-old debates of art versus commerce.

Vision Films released “Banksy and the Rise of Outlaw Art” on digital and VOD on February 18, 2020.