January 7, 2020

by Carla Hay

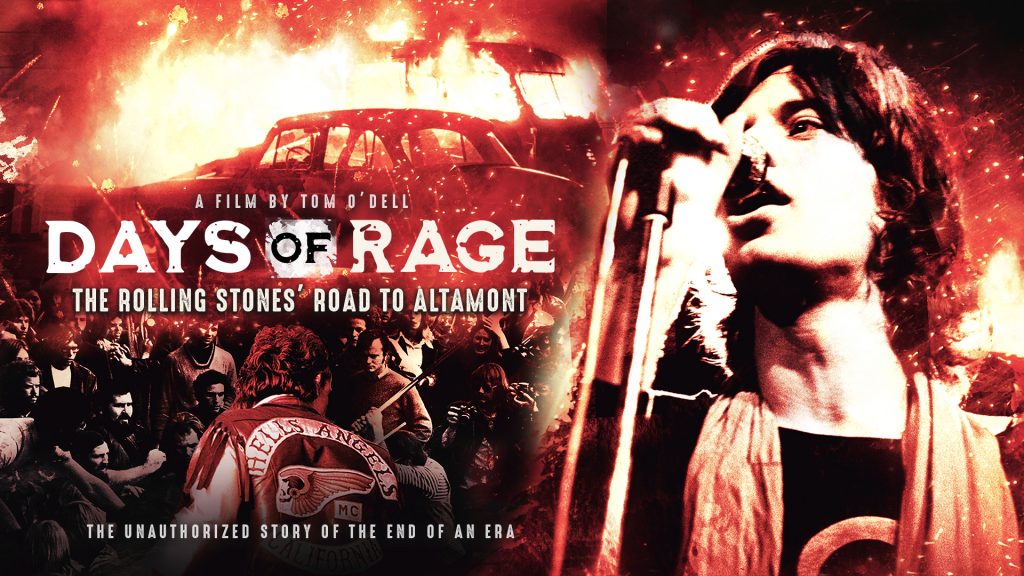

“Days of Rage: The Rolling Stones’ Road to Altamont”

Directed by Tom O’Dell

Culture Representation: A documentary about the disastrous and tragic Altamont concert headlined by the Rolling Stones in 1969, “Days of Rage” focuses on the era’s youthful counterculture movement and the business of rock music, as represented by white men who are British and American.

Culture Clash: In addition to showing a history of the 1960s counterculture and Generation Gap, the movie also examines how violence affected the factions of pop culture that were involved in the Altamont concert.

Culture Audience: “Days of Rage” will appeal primarily to Rolling Stones fans and people interested in learning more about how the Altamont concert became a notorious example of the dark side of the 1960s counterculture movement.

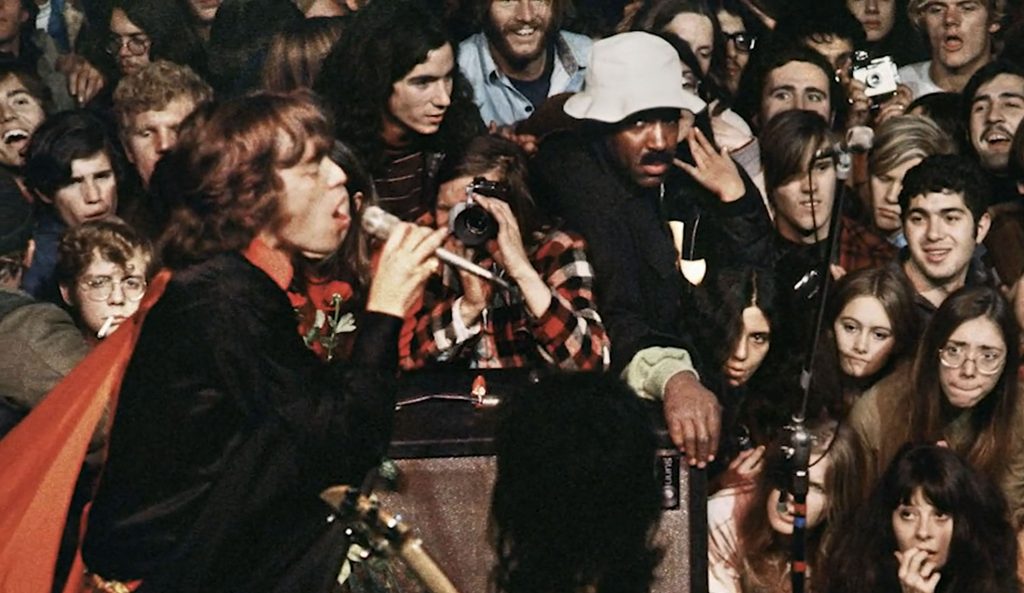

The first thing you should know about the absorbing documentary “Days of Rage: The Rolling Stones’ Road to Altamont” is that the Rolling Stones are not interviewed for this film. The second thing you should know is that the movie is not a rehash of “Gimme Shelter,” the 1970 documentary from director brothers Albert and David Maysles that chronicled the Rolling Stones’ ill-fated free Altamont concert in the San Francisco area on December 6, 1969. Even without the Rolling Stones’ participation, “Days of Rage” is a riveting historical account that explores much more than the Rolling Stones’ performance at Altamont concert. The movie takes an overall look at the circumstances and culture that led up to this tragic and violent event, during which an African American man named Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death in the audience by Hell’s Angels gang members while the Rolling Stones were performing “Sympathy for the Devil.” (The band didn’t perform the song for years after the tragedy happened.)

People who are interested in this documentary, which clocks in at a little over 100 minutes, should also know that the descriptions of the Altamont concert don’t come until the last third of the movie. The first two-thirds of the movie are a deep dive into how rock music and youth culture influenced each other in the 1960s, and led to the rise of the era’s counterculture movement. The 1960s counterculture was defined by rebellion against traditional establishment customs, and it included Vietnam War protests, liberal/left-wing politics, sexual liberation and rampant drug use, with marijuana and LSD being popular drugs of choice. Even though Altamont and the Rolling Stones are used as a hook in the title to sell this documentary, the movie is really about issues much larger than a rock band and a concert. The background information on how the 1960s counterculture happened might not be very revealing to aficionados who already know about the counterculture movement, but the documentary is a compelling visual journey into this part of history, regardless of how much knowledge people have about it.

Fortunately, director Tom O’Dell, who also wrote and edited “Days of Rage,” has constructed the story in such a fascinating way that viewers shouldn’t mind how long it takes for the film to get to the details of Altamont, since the preceding content provides much-needed context to explain how the Rolling Stones ended up in the most tragic moment of the band’s history. Unlike many unauthorized films about famous entertainers that are released direct to video, this isn’t a shoddy, “fly by night” money grab that interviews people with questionable credibility who have no connection to the artist. Two of the key people who were in the Rolling Stones’ inner circle in 1969 and who were at Altamont are interviewed for “Days of Rage”: former Rolling Stones tour manager Sam Cutler and Ronnie Schneider, who was a producer of the Rolling Stones’ 1969 tour.

The quality of “Days of Rage” is on par with a news documentary on CNN or BBC. Much of the Rolling Stones archival video footage in the documentary is from ABKCO, the company that owns the rights to most of the band’s 1960s recordings and official video archives. There are also clips from Rolling Stones documentaries, such as “Gimme Shelter,” “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Stones in the Park.” Given that “Days of Rage” is a low-budget independent film, the filmmakers wouldn’t have been able to afford the rights to license original recordings of Rolling Stones songs for use in the documentary, so generic facsimile music is used as the soundtrack instead, except for one snippet of the original recording of the Rolling Stones’ “Street Fighting Man.”

The documentary also includes the expected representation of authors and journalists (a mix of Brits and Americans) who provide commentary. They include “The Rolling Stones Discover America” author Michael Lydon, who attended the Altamont concert as a journalist; Rolling Stone magazine contributor Anthony DeCurtis; journalist Nigel Williamson, who’s known for his work for Uncut and Billboard magazines; “Altamont” author Joel Selvin, who was the San Francisco Chronicle’s pop-music critic from 1972 to 2009; Grateful Dead historian Peter Richardson; “Rolling Stones: Off the Record” author Mark Paytress; photographer Gered Mankowitz, who took some of the most iconic photos of the Rolling Stones in the 1960s; “1968 in America” author Joel Kaiser; and Keith Altham, who was a writer/editor at NME from 1964 to 1967, and who later became an entertainment publicist whose clients included the Rolling Stones. All of these talking heads provide articulate and insightful viewpoints. The documentary also benefits from the appealing British narration of Thomas Arnold.

The first third of the movie delves into the 1960s British Invasion (rock/pop acts from Great Britain taking over the American charts), the influential London youth culture, the Generation Gap and the Rolling Stones’ image as the rebellious antithesis to the more family-friendly Beatles. It was an image that was carefully crafted by Andrew Loog Oldham, a former publicist who was the Rolling Stones’ manager/producer from 1964 to 1967, when he was ousted in favor of American manager Allen Klein, whose background was in accounting. It was Klein who was a key player in the Rolling Stones getting lucrative record deals and becoming a top touring act, but he is described in most historical accounts of the Stones as a greedy bully who was involved in legal battles with the Stones for years after they fired him in 1969. (Klein, who died in 2009, founded the aforementioned ABKCO.)

The second third of the movie covers the rise of the counterculture in the mid-to-late 1960s, particularly in San Francisco, the home base of the Grateful Dead, which used Hell’s Angels gang members as peaceful security employees during the band’s concerts. (The Hell’s Angels were far from peaceful at Altamont.) All of these changes in society took place during the rise of LSD gurus Ken Kesey and Timothy Leary; California’s influential 1967 mass gatherings the Human Be-In (in San Francisco) and the Monterey Pop Festival; increasingly violent political protests; and the 1968 assassinations of civil-rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy.

During this era, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones (who had almost parallel careers in the 1960s) were part of the soundtracks to millions of people’s lives. The documentary notes the contrast between the two bands in the pivotal year of 1967: While the Beatles triumphed with the universally praised, artful masterpiece album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” and with anthems such as “All You Need Is Love,” the Rolling Stones stumbled with the critically panned album “Their Satanic Majesties Request” and the sardonic “We Love You” single, which failed to resonate with audiences on a wide level. The Rolling Stones were further sidelined in 1967 by legal problems for lead singer Mick Jagger, rhythm guitarist Keith Richards (the two chief songwriters of the Rolling Stones) and lead guitarist Brian Jones, who all got busted for drugs, resulting in jail time and scandalous trials.

But with civil unrest happening in many parts of the world, the Stones returned with a vengeance to the top of their game, marking the beginning of what many music historians and Stones fans consider to be the band’s best and most creative period in the late 1960s to early 1970s. The zenith of the Rolling Stones began in 1968 with the release of the single “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and the “Beggars Banquet” album, which included other Stones classics such as “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Street Fighting Man.” By 1969, the Stones were ready to tour again, this time with new guitarist Mick Taylor, the replacement for Rolling Stones co-founder Jones, who died by drowning on June 3, 1969, less than a month after he left the band. It was the first major lineup change to the Rolling Stones since the band began making records in 1963. The lineup was rounded out by drummer Charlie Watts and bass player Bill Wyman.

The Rolling Stones’ first concert with Taylor was a massive free show (with an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 people in attendance) at London’s Hyde Park on July 5, 1969, with the concert’s focus changing into a tribute to Jones because of his unexpected death. Even though the Hyde Park show was generally considered one of the worst concerts the Rolling Stones ever performed (their playing was out-of-tune and ragged), the show was a peaceful event with security provided by the British Hell’s Angels. The Hyde Park concert planted the seed for the idea of the Rolling Stones headlining a similar gigantic free concert in America, especially after the Woodstock Festival in August of 1969 became a cultural phenomenon. The Rolling Stones did not perform at Woodstock or the Monterey Pop Festival, and the documentary mentions that Jagger was particularly keen on performing at a huge counterculture event in America.

And when the Grateful Dead’s co-manager Rock Scully suggested that the Rolling Stones headline a free, one-day, Woodstock-inspired festival in San Francisco, with security provided by the Hell’s Angels, plans were set in motion for the concert that would become Altamont. In addition to the Rolling Stones, other bands on the bill were the Grateful Dead, Santana, Jefferson Airplane and the quartet Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. All four of these California-based acts except for CSN&Y member Neil Young had performed at Woodstock. The Rolling Stones’ “Let It Bleed” album (which included the classic single “Gimme Shelter”) was scheduled to be released just one day before the Altamont concert, which was essentially supposed to be a high-profile launching pad for the album.

The documentary points out that the British Hell’s Angels who provided security at the Rolling Stones’ Hyde Park concert were pussycats compared to their violent counterparts in America. Selvin further notes that the San Francisco chapter of the Hell’s Angels that the Grateful Dead worked with were much more benevolent than the “thugs” of the San Jose chapter of the Hell’s Angels who ended up committing the majority of the mayhem at the Altamont concert. The festival was so mismanaged that it never would have happened by today’s standards, due to all the present-day safety/insurance requirements and liability prevention policies that most U.S. cities, concert venues and promoters have. Plans to have the concert at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco were scrapped after the city refused a permit because the park wasn’t large enough for the expected audience size. The concert location was then changed to Sears Point Raceway in suburban Sonoma, but two days before the show, that concert site was cancelled after the Sears Point Raceway owners demanded exorbitant fees that the concert promoters weren’t willing to pay.

Out of sheer desperation, the concert was moved to the Altamont Speedway in suburban Livermore. The site, which was in a state of disrepair, was woefully ill-equipped to handle the crowd of an estimated 300,000 people who showed up. There were major problems with inadequate space, sanitation, food and medical facilities. Making matters worse, the stage was dangerously close to the crowd. At the Sears Point Raceway, the stage had been safely located at the top of a steep incline, so it was inaccessible to the audience. At the Altamont Speedway, the opposite was true—the stage had to be built at the bottom of an incline—so it was very easy for audience members to slide down the incline and reach the bottom of the landfill pit where the stage was located. Attempts to put barricades around the incline proved to be ineffective.

Even with these production problems and the large quantities of illegal drugs taken by the audience, people interviewed in the documentary say that the concert would have been relatively peaceful if there hadn’t been a bad group of Hell’s Angels inflicting an excessive and disturbing amount of violence on innocent people. The documentary has a harrowing account of the inescapable sounds of people being beaten with pipes and other weapons by the gang members. And a few band members weren’t spared from the violence either. Jefferson Airplane singer Marty Balin was beaten when he tried to stop a Hell’s Angels assault. Jagger, upon arriving at the concert site, was punched in the face by a drugged-out audience member. Band members pleaded several times on stage for the violence to stop, but those pleas were essentially ignored, and it wasn’t unusual for a Hell’s Angel member to get up on stage and threaten the performers.

The Grateful Dead got so freaked out by the violence that they refused to perform and immediately left the area. Schneider, a nephew of former Rolling Stones manager Klein, was one of the chief people responsible for promoting the concert, and he partially blames the Grateful Dead for the escalating Altamont violence, because the band abandoned the show. Schneider believes that if the Grateful Dead had played, the band’s laid-back jamming would have mellowed out the audience. Instead, there was nothing to fill the long time gap left by the abrupt departure of the Grateful Dead, and the audience had to wait for hours before the Stones arrived, further ramping up the tensions and violence.

There are graphic descriptions of what happened during and after the murder of audience member Hunter. According to eyewitnesses, his bloodied body was shockingly placed on stage and then backstage during the Rolling Stones’ performance, in order for his body not to be further violated by the angry and out-of-control Hell’s Angels. These descriptions are not in the “Gimme Shelter” documentary, which rightfully edited out the most disturbing footage of the murder. (Hell’s Angel member Alan Passaro, who was arrested for the stabbing, claimed self-defense because Hunter had pulled out a gun. Passaro was later tried and acquitted of the murder in 1971.) Some of the commentators, especially Selvin, want it to be known that the Rolling Stones perpetuated a myth that the band didn’t know about the murder until after their performance. Selvin said that the lights were so bright on stage (since the concert was being filmed) and the audience was so close to the stage that it was impossible for people on stage not to see all the violence being committed just a few feet in front of them.

The documentary also includes a photo of Jagger looking at a group of people standing around what is said to be Hunter’s dead body on stage. According to Selvin, it was Jagger’s decision for the Rolling Stones to continue performing, even after Jagger knew that someone had been murdered during the band’s set. Since Jagger has not publicly discussed the murder in detail, and he’s not interviewed for this documentary, his side of the story isn’t presented. However, the implication from the Rolling Stones insiders (Cutler and Schneider) who were at the Altamont concert and who were interviewed for this film is that Jagger probably thought that the violence would get worse if the Stones didn’t finish their performance.

Richards briefly told his memories of Altamont in his 2010 memoir, “Life,” but he did not go into any of the gruesome details. Wyman (who quit the band in 1993) ended his 1990 memoir, “Stone Alone,” with the death of Jones, who died six months before Altamont happened. Wyman barely mentioned Altamont in his 2019 biographical documentary “The Quiet One.” Taylor (who quit the Rolling Stones in 1974) and Watts have also not opened up publicly about how much of the murder and body disposal they saw.

Even if you’re a die-hard Rolling Stones fan who’s read numerous accounts of the Altamont concert or if you’ve seen “Gimme Shelter,” watching “Days of Rage” will still make an impact in showing how the peace and love dream of the ’60s counterculture turned into a sickening and brutal nightmare that’s also a cautionary and very tragic tale.

Vision Films released “Days of Rage: The Rolling Stones’ Road to Altamont” on VOD and digital on January 7, 2020.