January 24, 2023

by Carla Hay

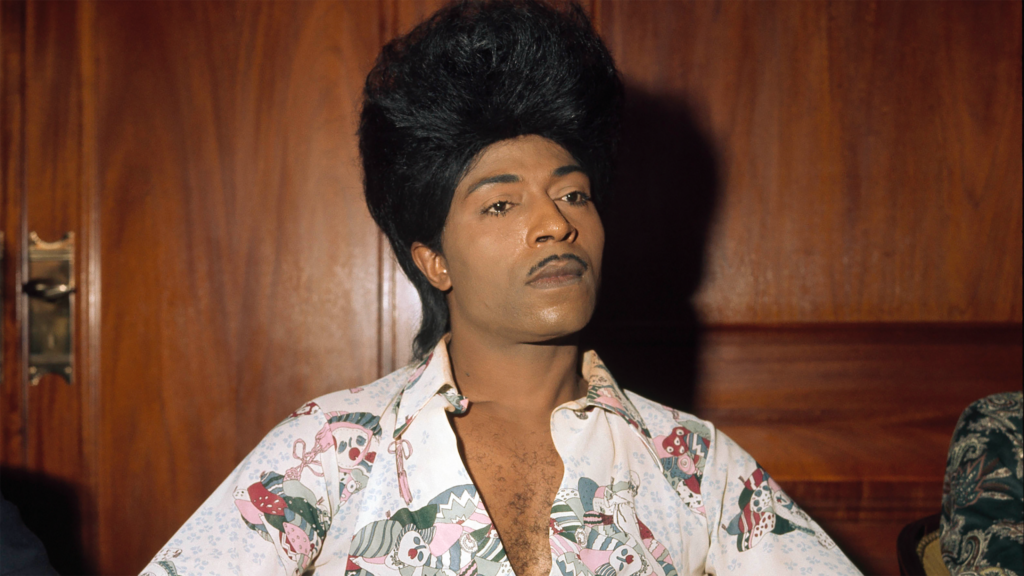

“Little Richard: I Am Everything”

Directed by Lisa Cortés

Culture Representation: In the documentary film “Little Richard: I Am Everything,” a group of African Americans and white people discuss the impact of rock and roll pioneer Little Richard, who died in 2020, at the age of 87.

Culture Clash: Little Richard experienced homophobia, racism, cultural appropriation, drug addiction and showbiz ripoffs during his many ups and downs.

Culture Audience: Besides appealing to the target audience of fans of Little Richard, “Little Richard: I Am Everything” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in watching documentaries about music legends who influenced countless entertainers.

“Little Richard: I Am Everything” vibrantly captures the spirit of rock music pioneer Little Richard and doesn’t shy away from exploring his many contradictions. The documentary stumbles by adding sparkly visual effects to make him look “magical,” but these corny embellishments don’t ruin the movie. “Little Richard: I Am Everything” can at least be applauded for not sticking to an entirely predictable format, since the movie does a few other things in its effort to not be a typical biographical documentary.

Directed by Lisa Cortés, “Little Richard: I Am Everything” had its world premiere at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival. The documentary unfolds in chronological order and has an expected mixture of archival footage of Little Richard (who died in 2020, at the age of 87) and exclusive documentary interviews with family members, associates, celebrity admirers and various culture experts. People don’t have to be fans of rock music to know that Little Richard was one of the originators of the genre. However, may people who are unfamiliar with him as an artist might be surprised by how his life went from one extreme to the other, often by his own doing.

People knowledgeable about rock history will also know already that Little Richard—just like other African American artists who were pioneers in rock music—was frequently ripped off creatively and financially. He was never fully appreciated by the industry when he was in the prime of his career. It was only after he loudly complained for years about not getting the recognition he deserved that he started to receive many industry accolades.

For example, Little Richard never won a Grammy Award in a competitive category (the Grammys Awards were launched in 1960, after Little Richard’s hitmaking career peaked), but he did receive a non-competitive Lifetime Achievement Grammy in 1993, long after he stopped making hit records. He was in the first group of artists inducted into the Rock and Roll of Fame in January 1986, but he couldn’t attend the ceremony because he had the bad luck of being seriously injured in a car accident in October 1985. (He fell asleep behind the wheel of the car.)

Born in Macon, Georgia, in 1932, Richard Wayne Penniman (Little Richard’s birth name) knew from an early age that he wanted to be a flamboyant entertainer, starting from when he used to dress up in his mother’s clothes when he was a child. Little Richard, who grew up in a strict Christian household, was the third-youngest of 12 children. His mother Leva Mae Penniman accepted him for who he was, but his father Charles “Bud” Penniman would brutally abuse Richard for being effeminate.

Bud Penniman was also a study in contradictions: He was church deacon and a brick mason, but he was also a bootlegger who owned a small nightclub and a house where he sold alcoholic drinks, which were illegal at the time. Ralph Harper, a former neighbor of the Penniman family, has this memory of Little Richard: “He was always banging on the piano, anytime you see him.”

Muriel Jackson, head of the Middle Georgia Archives, comments on Macon’s culture: “Macon is known for its churches. It’s a conservative, religious town.” Therefore, Little Richard wasn’t just bullied at home for being who he was. He also got a lot of abuse from other people in the community.

Specialty Records historian Billy Vera says, “They called him a sissy, a punk” and much worse. Emmy-winning and Tony-winning entertainer Billy Porter (who is openly gay) adds, “I can only imagine. I’ve lived a version of that. It’s debilitating. It’s soul-crushing. And it can be deadly.”

Little Richard spent the early years of his entertainment career in that vortex of contradictions: He would play the piano or sing in the choir in the stern atmosphere of conservative church gatherings, but he would also perform in the much-less restrictive (and taboo at the time) gay-friendly nightclubs in Macon and later Atlanta. He would often appear in drag at these shows under the stage name Princess LaVonne. In those days, it was illegal for men to dress in drag in public, unless they it was part of an entertainment act.

One of his frequent hangouts was Ann’s Tic Toc in Macon. And as a teenager, Little Richard worked at the Macon City Auditorium, where it made a huge impact on him to see many artists up close and backstage. The documentary mentions that when Little Richard saw his idol Sister Rosetta Tharpe (a guitar-playing vanguard in rock music) do a concert at the Macon City Auditorium in 1945, it changed his life. His piano-playing style was influenced by how Ike Turner played piano on Jackie Brenston’s 1957 song “Rocket 88.”

Little Richard was influential to countless artists, but there were people who influenced him on his artistic image/persona. In addition to Tharpe, another performer who helped shape Little Richard’s entertainment style was an openly gay drag performer named Billy Wright, who met Little Richard at the Gold Peacock nightclub in Atlanta in 1950, and they eventually became close friends. Wright had a pompadour hairstyle, wore heavy makeup, and had a thin moustache, which all eventually became signature looks for Little Richard. Did Little Richard copy Wright? Not really, as scholar Zandria Robinson explains: “They were kind of like mirrors that come into your life and show you who you really are.

In the early 1950s, black artists were limited to performing R&B, blues, jazz and gospel. The documentary mentions that when Little Richard was looking for a record deal, he didn’t quite fit in with any of these music genres, even though he was repeatedly told that he should perform blues, according to his longtime drummer Charles Connor. Instead, Little Richard was part of a small but growing number of black artists pioneering a new form of music that combined blues and R&B and made it more energetic, raucous and sexually frank. At first, this new form of music was called “race music” (to indicate that it was performed by black artists) but eventually became known as rock and roll.

Little Richard signed a deal with Signature Records. And his music as a rock artist eventually became hits not just on the R&B charts, but made their way as crossover hits on the pop charts. It’s mentioned that cars being made with radios had a big impact on people (especially the young people who tended to be rock fans) being able to listen to rock music away from home. It was during the 1950s that Little Richard had his biggest and most famous hits, including “Tutti Frutti” (a song that he later admitted was about anal sex, but he changed the lyrics before recording it), “Long Tall Sally,” “Good Golly, Miss Molly” and “Lucille.”

His stage act became known for his “let it all hang out” style of banging on the piano (often with a leg propped up on the piano) with passionate sexual energy that wasn’t often seen in piano players at the time. Little Richard was sexually ambiguous at a time when it was very dangerous for performers, especially male performers, to be sexually ambiguous. It’s noted in the documentary that Little Richard’s father eventually came to accept him after Richard became a local star in the Georgia music scene. Tragically, Bud Penniman was shot to death in 1952, outside his Tip In Inn nightclub. No suspect was ever charged with this murder, but Little Richard said for years that the culprit was Frank Tanner, who was Little Richard’s best friend at the time.

By 1956, Little Richard had moved to Los Angeles and brought many of his siblings with him. Several people in the documentary talk about how generous he was with family, friends and associates. Throughout it all, Little Richard’s mother was one of his biggest fans. Little Richard’s longtime drag-queen friend Sir Lady Java (an activist/entrepreneur) says in the documentary about Leva Mae Penniman: “She was such a beautiful person. She knew who he was and what he was. And she loved him in spite of it.”

Tom Jones says in the documentary that out of the five artists who are considered the first megastars of rock and roll—Little Richard, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis—”Little Richard was the strongest.” By the early 1960s, Little Richard was usually named as one of the biggest influences of a slew of British artists who were making their mark in rock and roll. The Beatles (who hung out with Little Richard in the band’s pre-fame nightclub stint in Liverpool, England, and in Hamburg, Germany) and the Rolling Stones jumped at the chance to perform on the same bill with Little Richard.

Robinson says that Little Richard’s upbringing in the South both tormented him and was inherent to who he was: “The South is the home of all things queer, of the different, of the non-normative, of the other side of gothic, of the grotesque. Note that queerness is not just about sexuality but about a presence and a space that is different from what we require or expect.” In other words, it doesn’t mean that queerness is more likely to be found in the South but that during Little Richard’s youth, the issues of race, social class and sexuality were more dangerous for people in certain parts of the South, such as his hometown of Macon, than in other parts of the United States.

After he became famous, Richard would change the descriptions of his sexual identity many times. Sometimes, he identified as gay. Sometimes, he identified as straight, during the periods of time when he became a born-again Christian who renounced any sexual identity that wasn’t heterosexual. Sometimes, he identified as bisexual or queer. Regardless of what his sexual identity was or was perceived to be, Little Richard could not be reasonably confused with any other entertainer because he had such a strong and distinct persona.

Rolling Stones lead singer Mick Jagger, who says Little Richard was one of his biggest influences, comments on Little Richard’s persona: “It was almost like having a split personality.” The Rolling Stones were the opening act for Little Richard at the beginning of the British band’s career in the early 1960s. Jagger said he used that opportunity to study Little Richard’s onstage persona: “I would be at the side of the stage to watch him. Richard would work that audience.” Jagger, who started his career with a performing style of standing still a lot on stage, changed that style and took on some of the same techniques that Little Richard used, and which Jagger still uses today.

Tony Newman, drummer of the British band Sounds Incorporated, has fond memories of working as a backup musician for Little Richard, whom he met in London in 1962. “Nearly every night,” Newman says, “it escalated into a full-blown riot in the theater. I remember coming off of that and thinking, ‘Now this is rock and roll!”

A great deal of the documentary repeats information that music historians already know but other people might not know about how much white artists and music companies owned by white people benefited and often ripped off the work of innovative black artists such as Little Richard. Elvis Presley and Pat Boone were two of the white artists who’ve famously done cover versions of Little Richard songs. The documentary points out that while Presley often acknowledged Little Richard for being an influence that was crucial to Presley’s success (Presley publicly called Little Richard the “real king of rock and roll”), Boone was not as gracious in admitting how much Boone was profiting off of music originally made by black artists such as Little Richard. In most cases, white artists got more money and recognition for performing songs originally performed by black artists than the black artists who were the originators of these songs.

This documentary didn’t have to do any real investigating to reveal any big secrets about Little Richard when it came to sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, because Little Richard told secrets about himself years ago in numerous interviews. The documentary includes clips of TV and radio interviews where he openly talks about indulging in sex orgies and experiencing drug addiction in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. He also participated in Charles White’s 1984 non-fiction tell-all book “The Life and Times of Little Richard,” which had a lot of details of Little Richard’s decadent lifestyle. The only viewers of this documentary who might be surprised by all this information are people who don’t know much about Little Richard.

As hedonistic as he admittedly was, there were periods of time in his life in the 1950s and the 1970s, when he denounced his “sinful” lifestyle and became a religious fanatic who gave up rock music to perform gospel music. In the late 1950s, he attended Oakwood University, a Seventh-day Adventist school in Huntsville, Alabama. These born-again Christian phases in his life often included Little Richard claiming that he was drug-free and no longer condoning of non-heterosexuality. This self-shame about his sexuality seemed to come and go in Little Richard’s life, which made him someone who was unpredictable and difficult for many people to figure out.

“Little Richard: I Am Everything” includes interviews with Lee Angel, who famously told the world decades ago that Little Richard seduced her in 1955, when she was 16 years old, and he asked her to marry him, but she said no. In the documentary, Angel says she’s not convinced that Little Richard was ever 100% gay. “He slept with me, and I’m all woman,” she declares proudly, although she admits she was initially surprised that he was sexually attracted to her because she thought he was more sexually interested in men. (Angel passed away in 2022.) The documentary does not have interviews with any of Little Richard’s male ex-lovers.

During one of his born-again Christian phases, Little Richard married Ernestine Harvin (also known as Ernestine Campbell) in 1959. They divorced in 1964. Harvin is interviewed in the documentary (audio only, not on camera) and says of her marriage to Little Richard: “Richard was the kind of husband most women would want: always positive, loving and caring.” Was Little Richard sexually confused? As scholar Jason King sees it: “He was very good at liberating other people through example. He was not good at liberating himself.”

“Little Richard: I Am Everything” also includes some mention of Little Richard’s battles and complaints about being cheated out of royalties, due to signing recording contracts and publishing deals where he received little to no money. Music attorney John Branca says that a lot of these legal issues had to do with Little Richard breaching his contracts during the periods of time when he refused to perform rock music and only wanted to do gospel. However, it’s a common story that many famous music artists, regardless of their race, regret signing deals that they later said were ripoffs where the artists didn’t get paid and sometimes ended up owing money.

Regardless of how much money or how little money Little Richard made from record sales or songwriting royalties, he still managed to be a popular live act and would tour regularly until the later stages in his life. Little Richard also dabbled in acting, usually making guest appearances and cameos in movies and TV shows. His more memorable film roles were in the 1986 comedy “Down and Out in Beverly Hills” and the 1993 action film “Last Action Hero.” The documentary does not mention the 2000 NBC TV-movie biopic “Little Richard,” starring Leon, who is not interviewed in the documentary.

One of the ways that “Little Richard: I Am Everything” tries to be different from the usual music documentary is by having artists who aren’t very famous do performances of songs that helped influence or define Little Richard. Valerie June performs Tharpe’s “Strange Things Are Happening Every Day” in the segment that talks about Tharpe. Cory henry recreates Little Richard’s performance of “Tutti Frutti” at the Dew Drop Inn in New Orleans. John P. Kee performs “Standing in the Need” during the segment talking about one of Little Richard’s gospel music phases.

During these performances and in some footage of Little Richard, the documentary has visual effects of glowing dust that floats through the air, as if it’s some kind of magical aura from Little Richard that’s being passed though the ether. It’s not as cringeworthy as sparkling vampires in the “Twilight” movies, but it looks very over-the-top and quite unnecessary. Little Richard did not lead a fairytale life. There’s no need to conjure up images that he spread some kind of mystical dust, as if he’s some kind of character from a Disney animated movie. The fascinating stories told about Little Richard by himself and other people are more than enough to be intriguing.

Other people interviewed in the documentary include his cousins Newt Collier and Stanley Stewart; Little Richard’s former manager Ramon Hervey; filmmaker John Waters; ethnomusicologist Gredara Hadley; entertainment agent Libby Anthony; singer Nona Hendryx; historian Tavia Nyong’o; former Oakwood University classmate Dewitt Williams; former Little Richard road manager Keith Winslow, whose other was a teacher at Oakwood University; bass player Charles Glenn, who was in Little Richard’s band; booking agent Morris Roberts; and producer/songwriter Nile Rodgers, who says that David Bowie wanted Bowie’s 1983’s smash hit “Let’s Dance” album (which Rodgers produced) to be heavily influenced by Little Richard. The documentary could have used more interviews with female musicians other than Hendryx, but it’s an overall diverse mix of people.

“Little Richard: I Am Everything” keeps the storytelling lively, thanks to some great editing by Nyneve Laura Minnear and Jake Hostetter. There’s a particularly powerful montage near the end of the film that juxtaposes archival footage of Little Richard and all the artists who have been directly or indirectly influenced by him over the years, including Elton John, Bowie, Jagger, Prince, Lady Gaga, Lizzo, former “Pose” star Porter and Harry Styles. “Little Richard: I Am Everything” is a perfect title for this movie, because it shows how Little Richard was at times (often to a fault) all things to many people. However conflicted he might have been in his personal life and career, this documentary eloquently demonstrates how Little Richard represents the glory and pain of expressing yourself freely, no matter what the consequences.

Magnolia Films will release “Little Richard: I Am Everything” in select U.S. cinemas and on VOD on April 21, 2023, with sneak-preview screenings in select U.S. cinemas on April 11, 2023. CNN and HBO Max will premiere the movie on dates to be announced.