February 4, 2023

by Carla Hay

Directed by Maite Alberdi

Spanish with subtitles

Culture Representation: Taking place in Chile, the documentary film “The Eternal Memory” features an all-Chilean group of people representing the working-class and middle-class.

Culture Clash: The documentary chronicles several months in the lives of former actress/politician Paulina Urrutia and her husband Augusto Góngora, a former TV journalist who covered Chile’s civil unrest in the 1970s and 1980s, and who now has Alzheimer’s disease.

Culture Audience: “The Eternal Memory” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in non-fiction stories about couples who have a partner living with Alzheimer’s disease and an upper-middle-class perspective of Chilean history.

“The Eternal Memory” is a beautiful but slow-paced love story between two Chilean spouses who are living with the husband’s dementia. This intimate documentary shows paralells of the couple remembering their romance while not wanting to forget the sins and suffering of Chile under the rule of dictator Augusto Pinochet. Viewers of “The Eternal Memory” who are expecting a lot of drama in this movie will be disappointed or will have their patience tested. But for viewers willing to immerse themselves in this couple’s world, “The Eternal Memory” can be a thoughtful and emotionally moving experience.

Directed by Maite Alberdi, “The Eternal Memory” was filmed for an unspecified period of time in the early 2020s. The movie is a combination of home-video footage filmed for the documentary and archival footage from other sources. “The Eternal Memory” had its world premiere at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival, where it won the grand jury prize in the World Cinema Documentary Competition.

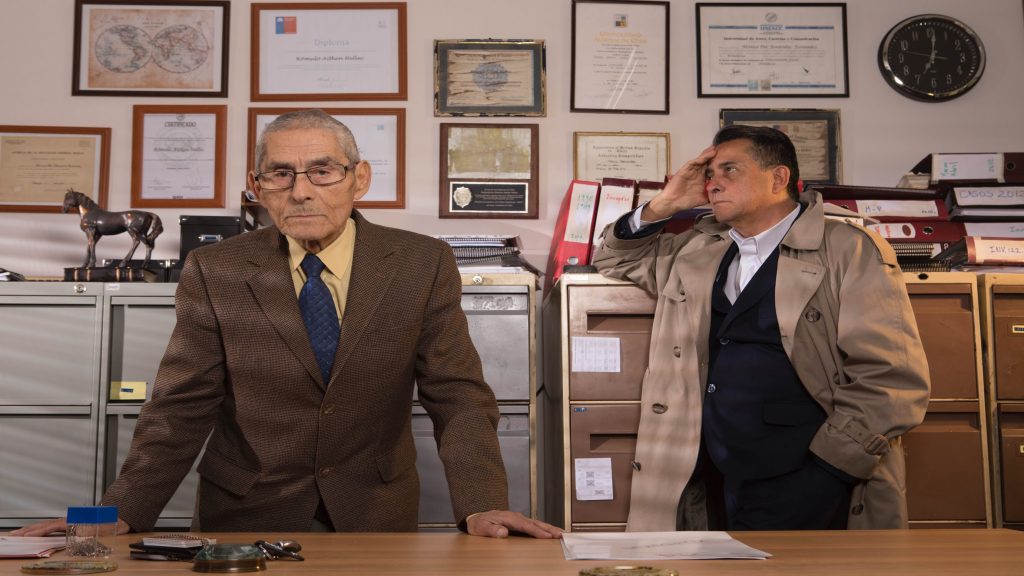

Alberdi previously directed the Oscar-nominated 2020 documentary “The Mole Agent,” which was about a Chilean senior citizen who was hired to check himself into a group retirement home, in order to find out more about the residents’ emotional well-being. “The Mole Agent” has themes of old age and the loneliness that elderly people can experience when they lose their memories or feel neglected. These themes are also in “The Eternal Memory,” but there’s a broader and more political context to the documentary that “The Mole Agent” did not have.

The two spouses at the center of “The Eternal Memory” are former actress-turned-politician Paulina “Pauli” Urrutia and former TV news journalist Augusto Góngora. The documentary shows repeatedly how devoted they are to each other, and they still have a romantic spark between them after being together for many years. Urrutia and Góngora became a couple in 1997, and they got married in 2016. Urrutia and Góngora have no children together, but some of the couple’s archival home videos in the documentary show them spending time with Góngora’s children Javiera and Cristóbal, from his previous marriage to Patricia Naut.

Born in 1969, Urrutia pursued an acting career since she was a child, eventually landing roles in Chilean movies and TV shows in the 1980s and 1990s. In the 21st century, she segued into politics. She was elected general secretary and president of the Chilean Actors Union (Sidarte) in 2001. And in 2006, she was appointed president of the National Council of Culture and the Arts.

Góngora also spent most of his life in the public eye. Born in 1952, Góngora is best known for his work as a TV news journalist in Chile, where he was a leader of the underground “Teleanálisis” newscast in the 1980s. He was a director and executive producer at Televisión Nacional de Chile (TVN) from 1980 to 2010. He also became a documentary filmmaker, with credits that include “The Weapons of Peace,” “Forbidden Children” and “The Seed of the Wind.”

In addition, Góngora dabbled in acting. A scene in the documentary shows Urrutia and Góngora reminiscing about the late filmmaker/actor Raúl Ruiz, who acted with Góngora in the 1997 miniseries “La Recta Provincia,” the only on-screen acting role that Góngora ever had. In “The Eternal Memory” scene, Urrutia asks Góngora if he remembers if Ruiz is alive or dead. Góngora says that he knows Ruiz is dead, and he remembers that Ruiz did not want to die.

Góngora was known for delivering hard-hitting investigations of the country’s civil unrest during the 1973 to 1990 reign of right-wing military dictator Augusto Pinochet. During this turbulent era in Chilean history, more than 3,000 people went missing or were found murdered. Thousands of children were orphaned. A scene in the “The Eternal Memory” shows Góngora and Urrutia morosely remembering a mutual friend named Jose Manuel Parada, who was kidnapped during the Pinochet regime.

Having to report these atrocities and other tragedies left a deep impact on Góngora, who seems to still be haunted by some of these memories. In addition to archival news footage of Góngora on the job as a TV news journalist, there’s footage of Góngora speaking about social injustice while promoting the non-fiction book “Chile: La Memoria Prohibida,” which he co-authored with other journalists. (“Chile: La Memoria Prohibida” means “Chile: The Forbidden Memory” in Spanish.)

Archival footage of Góngora shows that he was one of the first TV news journalists in Chile who advocated for citizen video journalism, where everyday citizens who are not professional journalists filmed their own footage that mainstream TV news would later used and give credit to these non-journalists who filmed the footage. Long before social media and viral videos ever existed, citizen video journalism was a form of journalism that started to increase in 1980s, when portable video cameras became more affordable to the average person.

Góngora is seen commenting in some 1980s footage, where she shares his thoughts about citizen video journalism: “We had the wonderful task of displaying the images of a country that was invisible in Chile, but a country that existed. We started giving an everyday version that did not appear on any Chilean TV station.”

There’s some archival footage of Urrutia when she was a politician, but the tone of “The Forgotten Memory” seems to be that the work that Góngora did was much more important than Urrutia’s work. Góngora’s career gets most of the screen time in the segments that show Góngora’s and Urrutia’s work lives before they retired. Urrutia is now Góngora’s full-time caretaker. If she has any help inside the home, it’s not shown in the documentary.

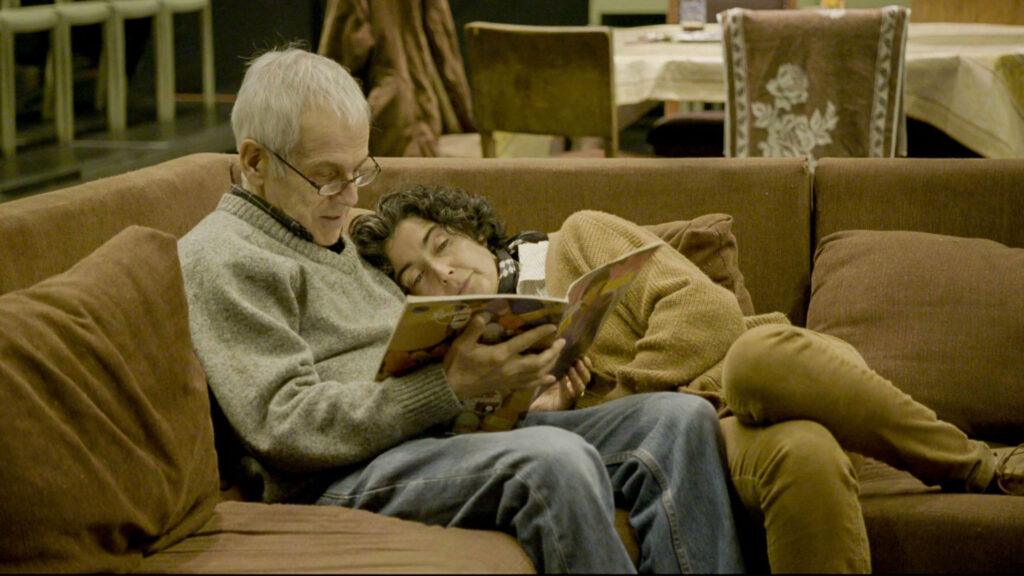

“The Forgotten Memory” has an abundance of everyday footage of Urrutia and Góngora at home talking about their lives. The movie opens with Góngora waking up in bed and remembering his name but not remembering who Urrutia is. She has to remind him that she is his wife, and she used to be an actress. She also tells him that he has two siblings and that his children’s names are Cristóbal and Javiera.

Urrutia and Góngora are shown doing couple activities, such as going for walks together and having meals together. She sometimes has to feed him because he can’t feed himself. During their walks outside, Góngora occasionally expresses mild frustration that he can’t walk as fast and as nimbly as he could when he was younger. They are physically affectionate with each other, such as when Urrutia lovingly dries Góngora with a towel after he gets out of a shower, or when they hold each other and kiss like partners who are best friends and in love.

Some of the most emotionally tender moments in the documentary are when Góngora is fully aware of who Urrutia is and expresses love and gratitude for her being in his life. In a scene where the spouses are having dinner together, he tells Urrutia in an appreciative manner, “You have given me so many things.” He also calls her “beautiful” while she silently sheds tears and smiles. In another scene, Góngora supportively watches in the audience when Urrutia performs on stage for a local theater group.

Through it all, Urrutia is extraordinarily patient, kind and emotionally strong. The documentary never shows her having any tearful meltdowns, expressing fear, or admitting that things can be sad and overwhelming when living with someone who has dementia. In that respect, “The Forgotten Memory” unfortunately gives the impression that it’s glossing over any emotional stress that Urrutia is no doubt having from being a caretaker of spouse with dementia.

When “The Forgotten Memory” tries to make Urrutia look so saint-like, it actually becomes a flaw in the documentary, which seems to leave out uncomfortable truths about the emotional toll and sometimes resentment that can build up when someone has the entire responsibility of taking care of a loved one with dementia. No one is realistically that saint-like all the time. Because the original footage in “The Forgotten Memory” is filmed cinéma vérité-style, there are no “talking head” interviews to provide outside analysis of what is going on with this couple.

Perhaps in an effort to give the image that she’s a “superwoman” spouse, Urrutia doesn’t really open up about any inner turmoil she is feeling, or her thoughts on preparing for the inevitable end of Góngora’s life. In front of the camera, she is upbeat but very emotionally guarded in other ways. The documentary would have been better and perhaps more helpful to people going through similar situations if Urrutia had been candid about her vulnerabilities of feeling emotional pain, doubt and hopelessness.

“The Eternal Memory” looks more honest in the uncensored moments when Góngora starts rambling about his frustrations. There’s a scene where Góngora gets very distraught because he knows he’s losing his memory, and he laments the loss of friends. He also says he doesn’t want to go on like this any more and that he feels alone. Urrutia’s response is to hug him and assure him that he’s not alone.

What remains unspoken but is seen in the documentary is that Urrutia and Góngora are very much alone during most of their time at home. The documentary doesn’t really show them having any visitors on a regular basis. It’s never fully explored how the couple feels about being “abandoned” by the friends who faded away from the couple’s lives.

One can imagine that the couple had plenty of friends when Urrutia and Góngora had elite positions that gave Urrutia and Góngora a certain amount of fame. Where are those friends now? Observant viewers will notice that this is the type of loss that is perhaps too painful for Urrutia and Góngora to talk about at length on camera.

It’s implied but not said out loud that these former friends were too uncomfortable with seeing Góngora living with Alzheimer’s disease. In one of the movie’s emotionally touching scenes, Góngora mournfully says out loud to himself, “No one asks me, ‘Remember when’ anymore.” As for Góngora’s adult children, they are not in the documentary’s new footage, and there is no explanation for their absence.

Urrutia and Góngora might feel a certain sense of isolation and abandonment from people who used to be close to them, but “The Eternal Memory” wonderfully shows how these two spouses have each other in a loving and emotionally healthy relationship. In the documentary, Góngora tells Urrutia that he doesn’t want to live for many more years. Whatever happens to this husband and wife, they both have had lives well-lived, with “The Eternal Documentary” being an impressive testament to their enduring love. The movie doesn’t tell the whole story of their relationship, but what is shown is meaningful and inspiring.

UPDATE: MTV Documentary Films will release “The Eternal Memory” in New York City on August 11, 2023, and in Los Angeles on August 18, 2023.