January 15, 2024

by Carla Hay

Directed by George C. Wolfe

Culture Representation: Taking place in the United States, from 1960 to 1963, the dramatic film “Rustin” (based on real events) features a predominantly African American cast of characters (with some white people) representing the working-class and middle-class.

Culture Clash: Openly gay activist Bayard Rustin battles people inside and outside the civil rights movement in his plans for a large-scale peaceful protest in Washington, D.C., while his personal life has various entanglements.

Culture Audience: “Rustin” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in watching a compelling but somewhat formulaic biography about an influential civil rights activist who has historically been overshadowed by more famous people.

Colman Domingo gives a commanding and charismatic performance in “Rustin,” a briskly paced drama that tells the story of underrated civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, who fought several public and private battles against racism and homophobia. It’s the type of movie that never lets you forget that you’re watching a drama, because the main characters often talk as if they’re giving speeches and lectures instead of having normal conversations. The movie delivers plenty of inspiration and heartfelt moments, but it zips around so much, some viewers will think that “Rustin” is a bit shallow and formulaic.

Directed by George C. Wolfe, “Rustin” had its world premiere at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival. Dustin Lance Black (the Oscar-winning screenwriter of 2008’s “Milk”) and Julian Breece co-wrote the screenplay for “Rustin.” The “Rustin” screenplay isn’t Oscar-worthy, but it has many memorable moments because of the way that the cast members interpret the dialogue. For the purposes of this review, the real Bayard Rustin (who died in 1987, at the age of 75) will be referred to by his last name, while the movie character of Bayard Rustin will be referred to by his first name.

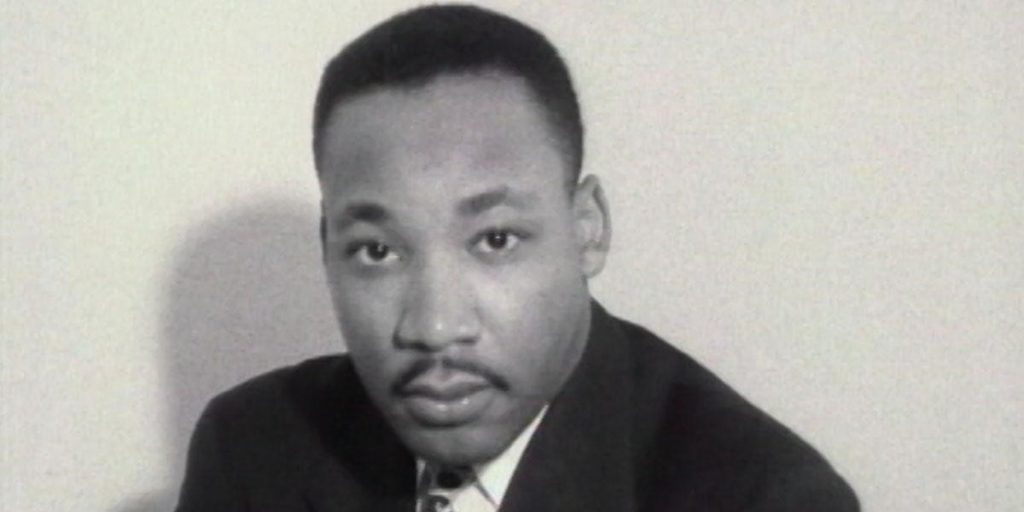

“Rustin” is not a comprehensive biopic, since the story takes place only during the years 1960 to 1963. However, the movie capably shows how Rustin is an often-overlooked influence in the U.S. civil rights movement and was a driving force in the historic 1963 March on Washington. Not all of the movie’s dialogue and scenarios are believable, such as the way that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (played by Aml Ameen) becomes almost like a sidekick character whenever Bayard (played by Domingo) goes on rants about how Bayard wants things to be.

Although “Rustin” shows Bayard experiencing violent racism (shown mostly in quick flashbacks), the biggest conflicts he has in the movie is with other civil rights officials. “Rustin” takes a realistic look at how internal power struggles and feuds within the U.S. civil rights movement often caused damage to the movement and/or slowed down progress. And in case it isn’t obvious to viewers, Bayard points it out in a preachy comment after preachy comment that racism isn’t the only enemy to the civil rights movement.

Early on in the movie (which is told in chronological order), Adam Clayton Powell (played by Jeffrey Wright) tries to ruin Bayard’s reputation by spreading stories that Bayard (an openly gay bachelor with no children) and Martin (a married father) are secret lovers. Bayard vehemently denies this accusation and puts in his resignation notice with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), because he thinks that Martin will back up Bayard and publicly urge him not to leave the NAACP.

However, Bayard (who was based in New York City during this time) doesn’t get Martin’s support, and the NAACP accepts Bayard’s resignation. It leads to a period of estrangement between Martin and Bayard, who becomes disillusioned with the NAACP and other aspects of the civil rights movement. Congressman Powell is portrayed as a power-hungry liar, but he isn’t the only person who becomes an enemy of Bayard.

Bayard’s main adversary in the movie is NAACP executive secretary Roy Wilkins (played by Chris Rock), who disagrees with Bayard on almost everything. When Bayard comes up with the idea of having a massive protest that would bus in at least 100,000 people from around the United States, Roy tells anyone who’ll listen that it’s a terrible idea because Roy thinks the event would be too expensive and too hard to manage. The 1963 March on Washington ended up getting a crowd of about 250,000 people.

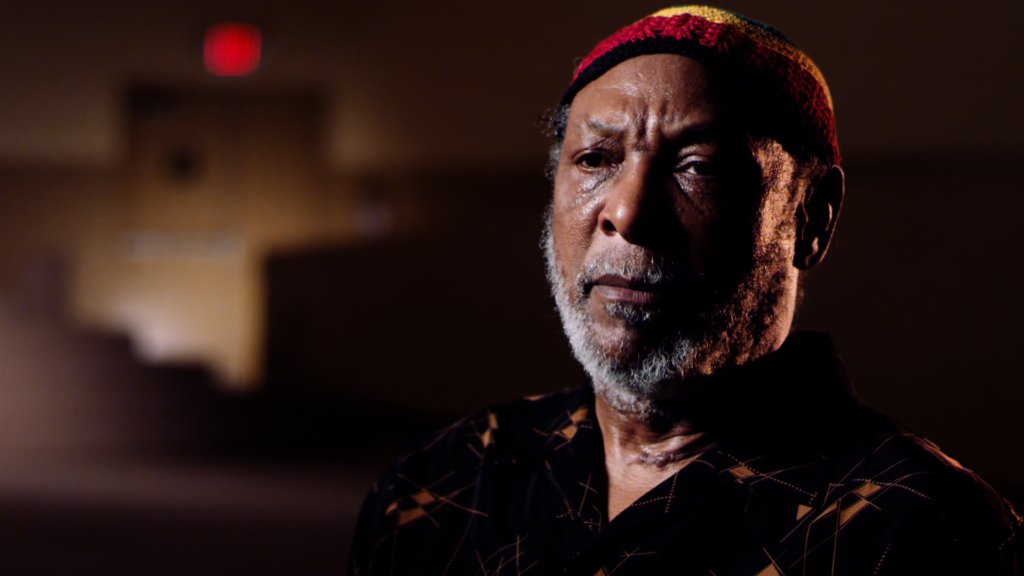

Roy (who is portrayed as egotistical and stubborn) also puts up a lot of resistance to Bayard’s plan to make it a two-day event, because Roy thinks a one-day event is more realistic. Bayard’s most loyal ally in these conflicts is union organizer A. Philip Randolph (played by Glynn Turman), who is like a father figure to Bayard. Bayard’s biological family is not part of the story. (It can be assumed he’s estranged from his family members because they disapprove of his sexuality.)

Meanwhile, although Bayard is open about his sexuality to the people who are closest to him, he struggles with finding a life partner because he’s a workaholic who’s afraid of committing himself to one person. In real life, Rustin often blurred his personal and professional lives, by hiring his lovers as his assistants. He also frequently dated younger men, many who were white. In the movie, the character of Tom (played by Gus Halper), a white worker for the NAACP who becomes Bayard’s assistant, isn’t based on anyone specific but is a composite of these types of men who would be sexually involved with Bayard.

Tom’s on-again/off-again relationship with Bayard gets sidelined in the story when Bayard has a deeper emotional connection with a closeted Christian preacher named Elias Taylor (played by Johnny Ramey), whose wife Claudia Taylor (played by Adrienne Warren) expects Elias to be the heir to her pastor father’s church. “Rustin” gives glimpses into Bayard’s nightlife activities, such as Bayard going to gay bars or cruising for sex partners on the street, but these are very fleeting glimpses. During this time when it was illegal in the U.S. to be homosexual or queer, the movie has one scene showing law enforcement raiding a gay bar that Bayard frequented. Bayard luckily avoids getting arrested in this raid because he wasn’t in the bar at the time.

“Rustin” gives only a very short acknowledgement that although women were valuable members of the civil rights movement, women were often overlooked and underappreciated when it came to who got the most power and the most glory in the movement. Dr. Anna Hedgeman (played by CCH Pounder) is depicted as the character who is the most outspoken about this sexism. Bayard temporarily appeases her by having her be a mid-level manager in the activities that he plans.

Although Bayard shows empathy and support for the women closest to him—including civil rights activist Ella Baker (played by Audra McDonald)—in the end, he doesn’t place a high priority on elevating qualified women into the highest positions of power. The movie has numerous scenes of meetings with African American civil rights leaders, and there are no women in the room. Almost all of the people whom Bayard personally mentors are other men, including an eager young activist named Courtney (played by Jeffrey Mackenzie Jordan), who has a platonic relationship with Bayard.

Meanwhile, most of the female actors in the movie are portraying characters who don’t have names and mostly do the work of assistants and secretaries. Martin’s wife Coretta Scott King (played by Carra Patterson), who doesn’t have much screen time in “Rustin,” is shown in the movie only as a housewife, which is what her husband wanted her to be. In real life, she had a college education and her own accomplishments outside of being a wife and mother. Da’Vine Joy Randolph makes a cameo as Mahalia Jackson performing at a rally led by Martin, but this scene-stealing appearance gives no further insight into Jackson’s involvement in the civil rights movement.

Because “Rustin” tends to make Bayard a forceful and dominating presence in every scene that he’s in, other important civil rights leaders are reduced to a handful of soundbites. They include John Lewis (played by Maxwell Whittington-Cooper), Medger Evers (played by Rashad Demond Edwards), Cleve Robinson (played by Michael Potts), Whitney Young (played by Kevin Mambo) and James “Jim” Farmer (played by Frank Harts). The obvious intention is to make Bayard look larger-than-life, but it’s often to the detriment of realism and development of other characters in the story that should have been depicted in a more meaningful way.

Some of the movie’s dialogue is a little hokey. For example, in a scene with Tom and Bayard in Bayard’s home, Tom is getting ready to smoke a marijuana joint. Bayard mildly scolds him by saying about smoking marijuana: “Last time I checked, that was illegal.” Tom replies, “Last time I checked, we were illegal.”

But the movie also delivers some memorable zingers, such as a scene where Bayard confronts Martin about homophobia among civil rights officials: “On the day I was born black, I was also born homosexual. They either believe in freedom and justice for all, or they do not.”

“Rustin” has a very talented cast, but it’s less of an ensemble movie and more of a showcase for Colman, who admirably brings a lot of soul and vigor to the role. Ameen is very good in the role of Dr. King, but the movie makes the Dr. King character become secondary to Bayard’s outspoken presence whenever they’re in the same room together. It’s a little hard to believe that Dr. King, who had his own strong personality, would be this subdued around someone with less power and less authority in making decisions for the civil rights movement. The movie gives credit to Rustin for influencing Dr. King to follow the non-violent philosophies of Mahatma Ghandi.

“Rustin” wants to make a point of how the real Rustin didn’t get enough credit for things he did behind the scenes in the civil rights movement. But by making him such a big personality who put himself at the center of conflicts, “Rustin” somewhat contradicts this movie’s message that the real Rustin was easily overlooked because he wanted to “fly under the radar.” It’s not until near the end of the movie that the character of Bayard shows humility in not seeking the spotlight for himself in the civil rights movement. A few more of these humble moments would have made the character more interesting and the movie more convincing in its premise that Rustin didn’t really want the widespread public recognition that he deserved.

Netflix released “Rustin” in select U.S. cinemas on November 3, 2023. The movie premiered on Netflix on November 17, 2023.