November 24, 2022

by Carla Hay

Directed by Prichard Smith

Culture Representation: The documentary film “The Invaders” features an all-African American group of people discussing the rise and fall of the Memphis, Tennessee-based militant Black Power group the Invaders, which formed in 1967 and disbanded a few years later.

Culture Clash: Former members of the Invaders say that were wrongfully blamed for a riot that broke out in Memphis in March 1968, during a protest in support of a labor strike by the city’s African American sanitation workers.

Culture Audience: “The Invaders” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in documentaries about the U.S. civil rights movement in the late 1960s.

When most people think of the Black Power movement that gained momentum in the U.S. in the late 1960s, they think of the Black Panthers. Many people don’t know about the smaller, grassroots Black Power groups that had similar ideals and made an impact. “The Invaders” documentary tells the story of one such group formed in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1967. This traditionally made documentary gives insight into the Invaders and their contributions to the U.S. civil rights movement of the 1960s. It’s an important reminder that the Black Panthers weren’t the only Black Power group making history.

Directed by Prichard Smith, “The Invaders” had its world premiere at DOC NYC in 2015. The movie’s release was in limbo for several years because of funding and licensing issues, according to a 2022 interview that Prichard Smith did with the Memphis Flyer, a local newspaper. Seven years after its world premiere at DOC NYC, “The Invaders” has now been released. The documentary is a conventionally structured mixture of archival footage and more recent interviews with former members and associates of the Invaders. What’s been added since “The Invaders” made the rounds on the film festival circuit is voiceover narration from Nasir Jones (better known as rapper Nas), who signed on as an executive producer for the documentary.

“The Invaders” opens with archival footage of Invaders co-founder Coby Smith (no relation to Prichard Smith) being interviewed by an unnamed media outlet in the late 1960s. He says, “We don’t organize burnings, essentially. We organize people. If people burn, they burn. We are black, and we’re proud of it.”

Much of “The Invaders” explores the theme of how there were two types of philosophies for the U.S. civil rights movement, when it came to race relations: One was the philosophy of non-violence, espoused by civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther Ling Jr. The other was the philosophy of violence in self-defense, espoused by civil rights leader Malcolm X and later the Black Panthers. What a lot of people don’t know is that King sought out the Invaders to be a bridge between these two philosophies.

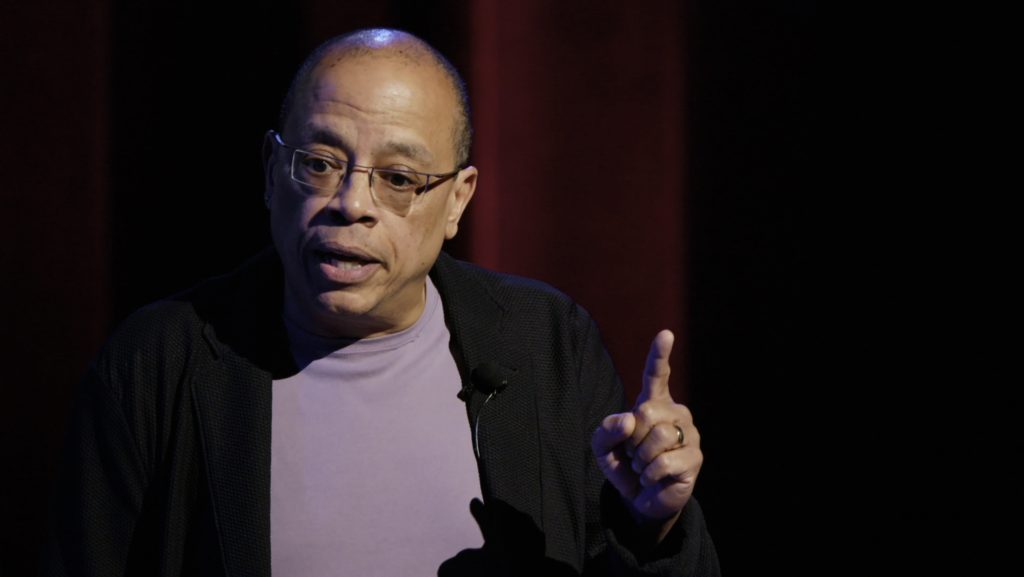

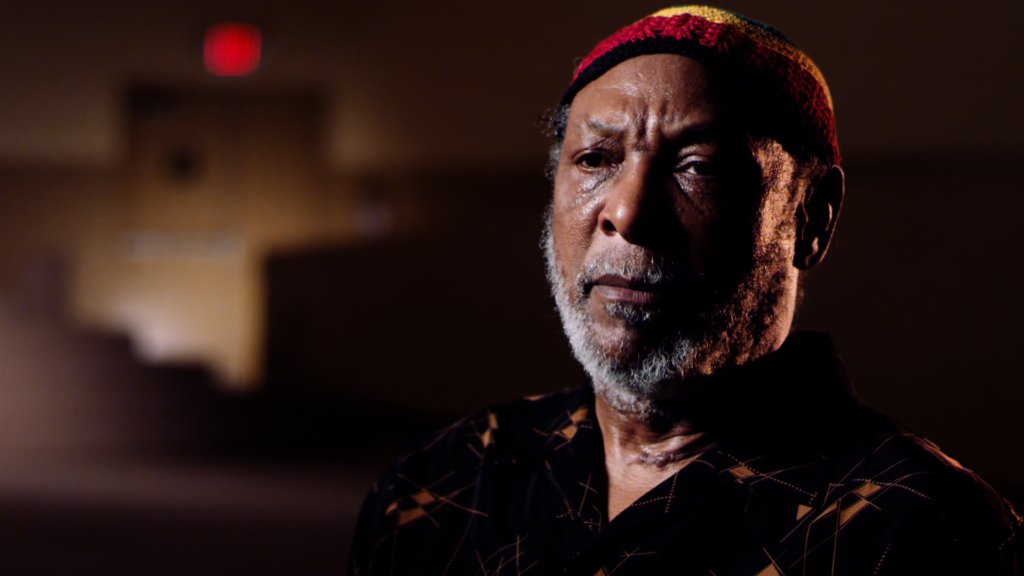

Among the people who tell the story in “The Invaders” documentary are Invaders co-founders Coby Smith and John B. Smith, who are not related to each other and not related to director Prichard Smith. Coby Smith and John B. Smith share vivid memories of meeting and forming the Invaders in 1967 with co-founder Charles Cabbage, who died in 2010, at the age of 66.

At the time the Invaders launched, Coby Smith and Cabbage were students and intellectuals who yearned to make a difference in African American communities in Memphis and beyond. John B. Smith was a disabled Vietnam War veteran who became disillusioned with the U.S. government after he came back from the war.

In the documentary, John B. Smith has this to say about what Memphis was like before the civil rights movement: “Segregation wasn’t just laws on the books. It was a state of mind. Black people understood what their place was, and they accepted that.” Calvin Taylor, former minister of information for the Invaders, adds: “When we were growing up, if you were black, that meant you were in the [racism] problem. It didn’t mean you had any opportunities not to be part of the problem.”

John B. Smith tells a story about the turning point when he decided to become a civil rights activist. He had returned from the Vietnam War and considered himself to be very patriotic about America. One day, he was at a gas station, minding his own business, when he saw a white man steal the gas cap from John B. Smith’s car. The alleged thief then tried to sell the gas cap back to John B. Smith.

John B. Smith responded by calling the police, who immediately took the white man’s side and believed the white man’s denials of stealing the gas cap, according to John B. Smith. The white man then accused John B. Smith of harassing him. A crowd gathered and defended John B. Smith, but the police theatened the crowd with arrest if they didn’t leave. John B. Smith says he refused to leave until the matter of the theft was resolved. And as a result, John B. Smith was arrested.

Influenced by Black Power activist Stokely Carmichael, the Invaders aimed to empower African Americans, beginning in Memphis, with fundraisers to help underprivileged people in the community. The Invaders were involved in the Black Organizing Project, which offered assistance in education and food for the African American community. Black Organizing Project also launched the Community Unification Program.

As the civil rights movement became more dangerous for activists and protestors, the Invaders also believed that black people were better off learning to arm and defend themselves against racist attackers. Juanita Thornton, one of the former Invaders interviewed in the documentary, says of this philosophy: “If you hit me, I should be able to hit you back without a whole lot of bullshit. I loved it.”

It was this militant stance that caused some civil rights leaders to mistrust the Invaders, while other civil right leaders wanted to align themselves with the Invaders. Reverend James Lawson, a civil rights activist who believed in non-violence, came from Nashville to Memphis and interacted for a time with the Invaders. Civil rights leader King became another ally of the Invaders, but he was assassinated (shot to death) on April 4, 1968, before his plans to create a formal alliance with the Invaders ever became a reality.

The Memphis sanitation strike, which lasted from February to April 1968, was the Invaders’ highest-profile protest campaign, for better or for worse. About 1,300 African American male sanitation workers from the Memphis Department of Public Works went on strike to demand higher wages and safer work environments that were the same given to the white sanitation workers who did the same jobs. Reverend Malcolm Blackburn, a white pastor of Clayborn Temple in Memphis, was an ally of the striking workers, and so were the Invaders.

Contrary to a mythical stereotype, Black Power activists such as the Invaders were not against working with white people in the civil rights movement. Coby Smith comments in the documentary: “We never would’ve gotten through the civil rights movement without an awful amount of whites who came and said [about racist laws/policies], ‘Wait a minute, that does not make sense.'”

On March 28, 1968, King and Lawson led a protest march in downtown Memphis, in support of the sanitation workers who were on strike. The march started out as peaceful but descended into chaos, as the mood turned angry. Some people in the crowd started looting and causing vandalism at nearby businesses. (King and Lawson left the protest soon after it became violent.) Police responded with aggression, including using mace and guns. In the resulting pandemonium, an unarmed 16-year-old African American named Larry Payne was shot to death in the stomach by a white cop.

The Invaders were blamed for inciting the riot, but it’s an allegation that the people in the documentary vehemently deny. Still, the riot tainted the Invaders’ reputation, and they say that key members of the Invaders became the targets of FBI surveillance, just like King was targeted by the FBI. Rather than distance himself from the Invaders, King sought them out for protection when he was at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, on that fateful day of his death. (James Earl Ray, who had a long criminal history of being a thief, pleaded guilty to the murder, and he was sentenced in 1969 to 99 years in prison. Ray died in 1998, at the age of 70.)

Still reeling from the damage and increased racial tensions caused by the riot and Payne’s death, about 15 members of the Invaders met with King for a few hours, at his request, at the Lorraine Motel on April 4, 1968. About half an hour after the Invaders left the motel, King was murdered. John B. Smith and Cabbage were among those who met with King, who told them that he wanted the Invaders to be the security personnel for the next planned protest in support of the Memphis sanitation workers on strike.

John B. Smith says that King confided in them about being under surveillance by the FBI because then-FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had a personal grudge against King. In the documentary, John B. Smith remembers that King told him about the famous private meeting that King and Hoover had in December 1964, after Hoover had publicly made this statement in November 1964: “Dr. Martin Luther King is the most notorious liar in the country.” (The December 1964 meeting was the only time that King and Hoover ever met face-to-face.)

According to John B. Smith, King went into the meeting with Hoover thinking one way and came out of the meeting thinking another way: “He [King] thought that they could actually come to a meeting of the mind. But once he met with him [Hoover], he realized that Hoover was out to destroy him.” King also said that the racists that King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference group encountered were worse in the Northern states than in the racially segregated Southern states.

Thornton says in the documentary that King wanted to take “the cream of the crop” of African American militants, such as the Invaders, and “put them into a training program that was non-violent.” Later in the documentary, Thornton says, “I believe economic power for poor people was one of the main reasons why Dr. King got assassinated. He was talking about poor people power.”

“The Invaders” is very no-frills when it comes to its editing and cinematography, but the interviewees are compelling and offer some valuable first-hand insights about their perspectives of the U.S. civil rights movement. Other people interviewed in the documentary are Reverend Jim Netters, who was on the Memphis City Council in 1968; Clarence Christian, who was a student activist at LeMoyne-Owen College in 1968; Mad Lads lead singer John Gary Williams, a former member of the Invaders; David Acey, who was a student protester in 1968; and Lance Watson, also known as Sweet Willie Wine, who led the Invaders’ security personnel. Watson later changed his name to Suhkara A. Yahweh. (Williams died in 2019, at the age of 73.)

As interesting as these stories are in “The Invaders,” this documentary doesn’t really reveal anything new. Some of the interviewees have talked about the same things in other media interviews before this documentary was made. John B. Smith also wrote a memoir titled “The 400th: From Slavery to Hip-Hop” (published in 2021), which covers many of the same things that are covered in the documentary.

“The Invaders” doesn’t go deep enough in taking a critical look at why a civil rights group such as the Invaders had very sexist attitudes in not letting women have leadership roles. Thornton (who was never a leader in the group) is the only woman interviewed in the documentary. The small percentage of female representation in this documentary is indicative of problems that the group had with sexism against women that the documentary completely ignores.

“The Invaders” also could have had perspectives from at least a few people who were involved in the civil rights movement in the late 1960s, but were not necessarily fans of the Invaders. The documentary seems to be a little too much of a praise fest for the Invaders and doesn’t offer any constructive criticism of the group, which eventually drifted apart and disbanded a few years after King’s assassination. Even with these flaws, “The Invaders” documentary is worth watching for history enthusiasts or anyone interested in a getting an inside story of an African American activist group that has often been relegated to being a footnote in U.S. civil rights history.

1091 Pictures released “The Invaders” on digital and VOD on November 1, 2022.