September 9, 2020

by Carla Hay

Directed by Ayumu Watanabe

Available in the original Japanese version (with English subtitles) or in a dubbed English-language version.

Culture Representation: This Japanese animated fantasy film takes place primarily in an unnamed Japanese city, with teenagers as the lead characters and adults as supporting characters, representing the middle-class.

Culture Clash: A teenage girl, whose scientist parents work at a local aquarium, encounters two mysterious aquatic teenage boys who were found at sea and who want to get away from the scientific experiments that have forced on them.

Culture Audience: “Children of the Sea” is a family-friendly film that will appeal mostly to fans of Japanese anime and animated adventure films.

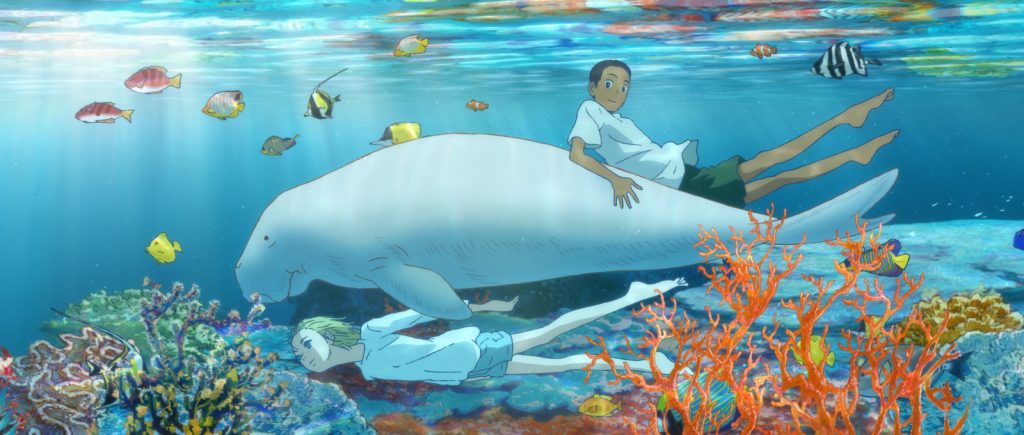

The gorgeous Japanese animated film “Children of the Sea” immerses viewers into a fantasy world that compares and contrasts life on land and life underwater, but there’s a very “real world” environmental message that is present throughout the story. Directed with both enchanting whimsy and technical prowess by Ayumu Watanabe, “Children of the Sea” has some eye-popping animated visuals that deserve to be seen on the biggest screen possible. Daisuke Igarashi wrote the “Children of the Sea” adapted screenplay from his manga of the same title.

The story, which takes place in an unnamed Japanese city. is told from the point of view of a teenage girl named Ruka Azumi (who’s about 15 or 16 years old) during her summer break from regular school sessions. Her vacation gets off to a rocky start when Ruka, who is a rugby player for her school, is wrongfully accused of starting a fight with a fellow student during rugby practice. The other student, who was playing on the opposing team, was the one who was the physical aggressor, because she deliberately tripped Ruka during the game.

A supervising teacher calls Ruka into his office and scolds her for being a “troublemaker.” He doesn’t want to hear Ruka’s excuse that the bullying student was the one who started the fight. And he tells Ruka that if she won’t apologize to the other student, then Ruka shouldn’t bother coming to practice anymore.

Feeling dejected and misunderstood, Ruka decides to go to Enokura Aquarium where her father Masaki works as a scientist. Ruka has happy memories of spending her childhood at the aquarium. One of these memories, which is shown at the beginning of the movie, is when Ruka saw a ghost in the aquarium. Her father is one of the aquarium’s scientists who evaluate aquatic life and do experiments, such as seeing how dolphins respond to certain sounds.

While at the aquarium, Ruka discovers a friendly teenage boy in a back room. He’s about the same age as Ruka, and his name is Umi. He shows Yuka that he has an extraordinary ability to swim and float underwater for long periods of time without any breathing equipment. Ruka is very intrigued by Umi and wants to become his friend.

Ruka’s father tells her that Umi was found 10 years ago with another boy off of the shores of the Philippines. Scientists discovered that Umi and the other boy (who is slightly older than Umi) were raised primarily underwater by dugongs. The boys, who are apparently orphaned and raised as brothers by the dugongs, were kept at the aquarium for research.

One evening, Umi invites Ruka to go with him to see a will o’ the wisp at the beach. Ruka is surprised to see what she thinks is a comet or shooting star, but Ruka insists that it’s a will o’ the wisp. He also tells Ruka that animals shine when they want to be found.

While at the beach, Ruka sees the teenager who is described as Umi’s adoptive older brother: His name is Sora, whose skin is so pale that at first Ruka thinks that Sora is a ghost. Sora has blonde hair and blue eyes, which implies that he’s of European descent, while Umi has the appearance of being Filipino. It’s never explained in the movie how Umi and Sora ended up being stranded at sea together, since both boys don’t seem to have any memories of their human families.

Unlike the amicable reaction that Ruka got from Umi when they first met, the first time she meets Sora, he’s rude to her. Sora tells Ruka that she’s “boring.” He adds, “Umi has me. He’s not interested in you.” It also becomes clear as the story unfolds that Sora is more rebellious and more impulsive than Umi.

Sora is growing tired of being a research subject and wants to spend less time away from the aquarium. This restlessness is one of the main reasons why Sora, Umi and Ruka end up taking a joyride on a boat. It isn’t until they’re in the middle of the sea and that Sora admits he doesn’t know how to sail the boat and he was just winging it as they went along. And so, when the boat’s engine mysteriously stalls, the three teens don’t know how to fix it.

It’s during this fateful boat ride that Ruka discovers Umi’s and Sora’s seemingly magical powers to communicate with the aquatic creatures. She also gets to experience underwater life for the first time in some of the movie’s most visually stunning sequences, including seeing whale shark creatures. Sora eventually warms up to Ruka, but he still feels leery about anyone he thinks might try to break his brotherly bond with Umi.

It’s implied that Ruka has special powers too, but she isn’t fully aware of them yet. Meanwhile, Umi and Sora tells her that numerous creatures in the ocean will be gathering for a Birth Festival underwater and are looking for festival guests. Sora says he’s been traveling the world with a scientist named Jim to research the festival’s connection to Umi and Sora.

The trio makes it back to shore, but it won’t be the last time Ruka, Umi and Sora go out to sea together and experience dangerous situations. There’s a boat they use called the Rwa Bhineda that is a key part of their adventures together. One of the people they encounter near the boat is Angurâdo, a young man who wants to be Jim’s assistant.

There’s also an aquarium scientist named Anglade, who wants to keep Umi and Somi at the aquarium for research, even though it’s becoming obvious that the teenagers are growing into young men and want more independence. And there’s a town eccentric named Dehdeh, an elderly woman with apparent psychic abilities.

Ruka is close to her father, but she has a tense relationship with her mother Kanako, a scientist who also works at the aquarium but is on a leave of absence. The reason is because she’s an alcoholic, which is a secret that has brought shame to the family and has caused Ruka to have resentful feelings toward her mother. Kanako’s work colleagues describe her as “brilliant,” but Ruka doesn’t have much respect for her mother because of how Kanako’s alcoholism has negatively affected the family. It’s one of the reasons why Ruka doesn’t like to spend much time at home.

“Children of the Sea” has subtle and not-so-subtle environmental messages about the world being destroyed by humans’ recklessness and greed. Climate change and how it’s affecting the environment are on display when a megamouth shark and hundreds of fish wash up dead on near the aquarium. A typhoon suddenly occurs during one part of the story. And the movie has constant themes of urgent messages that aquatic animals are trying to communicate with humans.

STUDIO4°C, the animation studio behind “Children of the Sea,” infuses this story of teen rebellion meets environmentalism with a lot of reverential images of aquatic life. Creatures such as dolphins and whales are portrayed as just as intelligent (and sometimes smarter) than humans. And underwater life, although certainly not a utopia, is presented as a lot more harmonious and tranquil than the land inhabited by destructive humans.

The animation also takes risks by having some truly psychedelic imagery toward the end of the movie. Joe Hisaishi’s musical score perfectly complements the mood of each scene. And even though “Children of the Sea” is longer than a typical animated film (the total running time is 111 minutes), director Watanabe makes it a well-paced story. Some of the characters are more layered than others, so viewers will want to keep watching to see what it all means in the end. (There’s also an end credits scene that shows an epilogue to the story.)

The voices of the “Children of the Sea” characters are portrayed by different actors, depending on the version of “Children of the Sea.” The original Japanese version (with English subtitles) has Mana Ashida as Ruka, Hiiro Ishibashi as Umi, Seishu Uragami as Sora, Win Morisaki as Anglade, Goro Inagaki as Masaki Azumi, Yu Aoi as Kanako Azumi, Toru Watanabe as The Teacher, Min Tanaka as Jim and Sumiko Fuji as Dehdeh. There’s also a U.S. version, with the dialogue dubbed in English, that has Anjali Gauld as Ruka, Lynden Prosser as Umi, Benjamin Niewood/Benjamin Niedens as Sora, Beau Bridgland as Anglade, as Marc Thompson as Masaki Azumi, Karen Strassman as Kanako Azumi, Wally Wingert as The Teacher, Michael Sorich as Jim and Denise Lee as Dehdeh.

Some adults might think that animation is mostly for kids, but “Children of the Sea” is a great example of an animated film that can tell an intriguing story that’s relatable to people of any generation. It’s clear that the movie has a viewpoint that if aquatic animals could talk, they would be begging humans to treat the underwater world with more respect because how underwater life is treated affects us all. The movie’s environmental message isn’t preachy, but it shows how people on land are connected to the life that’s underwater and how lessons learned from the past can shape the future.

GKIDS released “Children of the Sea” on digital, Blu-ray, DVD and Netflix on September 1, 2020.