August 27, 2023

by Carla Hay

“What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?”

Directed by John Scheinfeld

Culture Representation: The documentary “What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” features a nearly all-white group of people commenting on the career of North American jazz rock band Blood, Sweat & Tears, whose career peaked in the late 1960s.

Culture Clash: Blood, Sweat & Tears became a controversial group, after the band was hired in 1970 by the U.S. government to do a “cultural exchange” tour of Eastern European countries that were Communist at the time.

Culture Audience: “What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” will appeal primarily to viewers who are interested in watching documentaries about how music and politics intersect, for better or for worse.

“What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” is not a “where are they now” movie, as the title might imply. This documentary is a fascinating look into a rock band vilified by left wingers and right wingers because the band did a tour of Communist countries to promote cultural amity. It’s a cautionary tale of how good intentions can be twisted for agendas.

Directed by John Scheinfeld, “What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” features interviews with several of the musicians who were in this jazz-influenced rock band in 1970, when most of this story takes place. Those interviewed include singer David Clayton-Thomas, drummer/percussionist Bobby Colomby, bass guitarist Jim Fielder, alto saxophonist/keyboardist Fred Lipsius and multi-instrumentalist Steve Katz. All except Clayton-Thomas are original members of the band. In addition, the documentary has a treasure trove of previously unreleased archival footage.

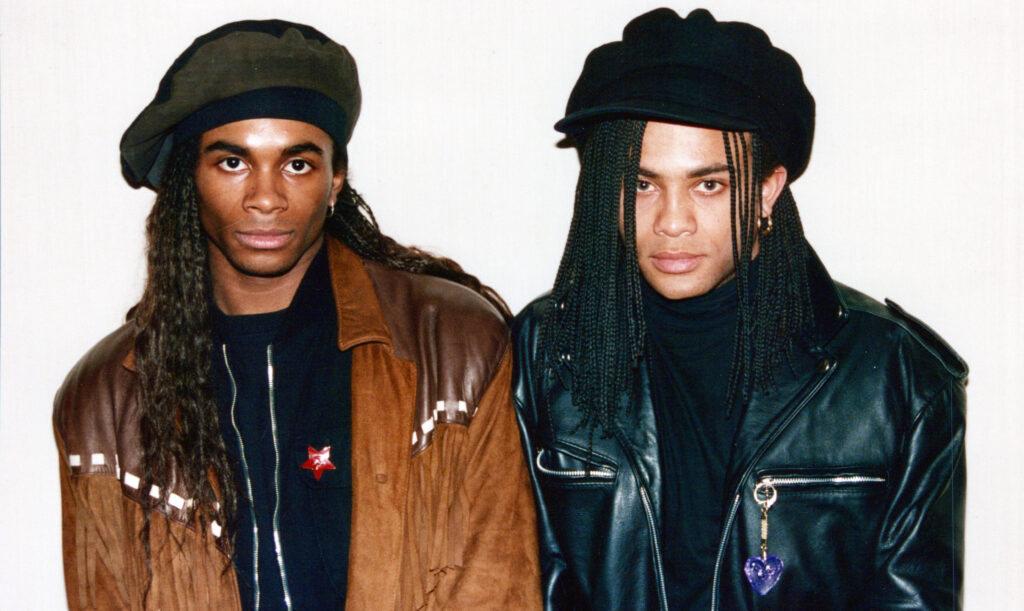

“What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” begins by giving a brief origin story of the band, which was formed in New York City in 1967, with lead singer Al Kooper. Blood, Sweat & Tears made a name for themselves for blending jazz with rock, as their songs prominently featured a horn section, and their live shows often had long, instrumental jams. Blood, Sweat & Tears signed with Columbia Records, which released the band’s 1968 debut album, “Child Is Father to the Man.”

That first album was a middling success. Creative difference led to Kooper departing as lead singer. He was replaced by Canadian singer Clayton-Thomas, who brought a soulful voice and charismatic stage presence to the band. Blood, Sweat & Tears’ self-titled second album, also released in 1968, would be the band’s breakthrough and has what are still the band’s best-known songs: “Spinning Wheel,” “And When I Die” and “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy.” The “Blood, Sweat & Tears” album was a chart-topping hit and went on to win the Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1970.

Sony Music Entertainment chief creative officer Clive Davis, who was president of Columbia Records at the time, says of Blood, Sweat & Tears in their prime in the music scene: “They weren’t fitting into it. They were leading the way.” Music writer/critic David Wild adds, “In terms of influence, you can’t imagine a world of horn rock and roll happening without them. They were just great. But even their greatness may have been problematic for them.”

It was during this peak period of the band’s commercial success that Clayton-Thomas got into some legal trouble that was the catalyst for the band’s controversial Iron Curtain tour. In late 1969, he was arrested at JFK Airport after a former girlfriend had accused him of threatening her with a gun two days earlier. Police investigated, and Clayton-Thomas was cleared of the accusation, which he says was a false accusation. In the documentary, he comments: “It was a nasty moment.”

Around the same time, U.S. State Department’s Cultural Presentations Program was looking for a way to ease the tense relations between the U.S. and “Iron Curtain” Communist countries in Europe, such as Yugoslavia, Romania, and Poland. Danielle Foster-Lussier, Ohio State University professor of music, explains: “At the time, there was a concern that the United States looked like a country of brute force power, military power. And there was the idea that the arts could make us look like we had soul.”

According to the band members, because of Clayton-Thomas’ arrest record and past visa issues, he was threatened with deportation by the U.S. government if Blood, Sweat & Tears did not sign on for the Iron Curtain tour, which was scheduled to take place from June 17 to July 7, 1970. Clayton-Thomas comments on his bandmates and then-Blood, Sweat & Tears manager Larry Goldblatt: “I was going to be deported … They were going to do everything they could to keep me in the band.

As part of the deal, the band’s usual fee ($25,000 per concert) was waived, but the U.S. government funded the tour. The Iron Curtain Tour was controversial from the start, including within the band. Katz, who was the band member who was against the idea the most, put it bluntly in the documentary on why the band did the tour: “We were blackmailed.”

Clayton-Thomas says in the documentary: “We were the No. 1 band in the world, and it turned into a political rat’s nest.” Fielder shares a different perspective: “We were excited about doing it. It seemed like a great way to expand the band’s popularity to a whole new audience.”

With the Iron Curtain Tour, Blood, Sweat & Tears became one of the first rock bands to tour in these Communist countries. The tour went to the cities of Zagreb, Ljubljana, Belgrade, and Sarajevo in Yugoslavia. Then it was on to Constanta and Bucharest in Romania. And the final stop was Warsaw in Poland.

The problem was that the Iron Curtain Tour alienated people on both ends of the political spectrum in the United States and elsewhere. Left wingers who had considered Blood, Sweat & Tears to be part of a left-wing counterculture movement were angry that the band seemed to be willingly working with the U.S. government, which was paying for the tour. Right wingers were against the idea of any North American band trying to become friendly with Communists.

Katz, who a self-described counterculture radical at the time, comments in the documentary about the Iron Curtain Tour: “I was horribly against it … I was political, but the guys in the band weren’t political … They were musicians first.”

Clayton-Thomas agrees and comments on Katz: “He was very radical and very much into radical politics. Me? Not so much. I’m Canadian. But we [Blood, Sweat & Tears] were very involved in the counterculture movement of the day, mostly based in the Vietnam War and the anti-war movement.”

“I think we were naive,” Clayton-Thomas says. “I don’t think we realized how it would bounce up and bite us. To his credit, Steve did.” Tim Naftali, founding director of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, comments in the documentary about the political climate in the U.S. at the time: “There was a national divide. And the national divide is defined in terms of [the war in] Vietnam.”

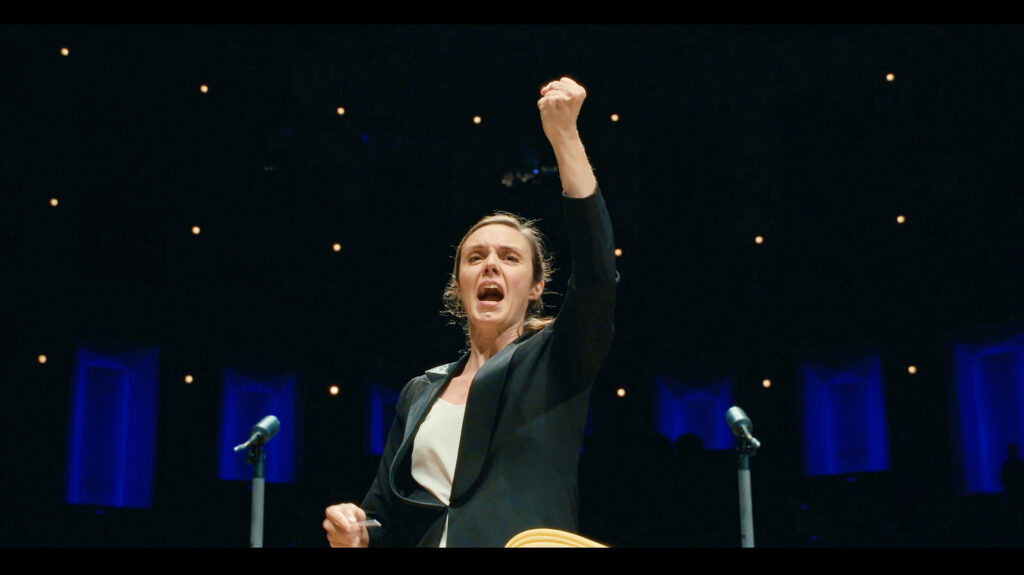

The tour was filmed for a documentary directed by Donn Cambern, in what was his first feature-length film. Much of the Cambern’s “long-lost” footage from the documentary (which was never released) has been restored as in “What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” In addition, the documentary includes archival audio from the tour. The concert footage is electrifying with very good sound quality.

Cambern comments, “This was my first real directing job. My vision was to make a concert film. When we arrived in Zagreb [in the country then known as Yugoslavia], things changed. It was nerve-wracking but very exciting.”

The tour was a very eye-opening experience (both good and bad) for Blood, Sweat & Tears. On the one hand, they audiences were welcoming at almost all of the concerts. On the other hand, the band was constantly under surveillance while in these Communists countries. Band members tell stories in the documentary of being followed and having their photos taken by men who obviously worked for the country’s government.

Things got very ugly when aggressive security officers would brutally assault audience members. Fielder almost breaks down and cries at the memory of a male fan being severely beaten backstage, just because the fan asked band members for an autograph. There was violence in other ways at a few of the concerts, such as dogs being sent to attack concertgoers. A fire that was believed to be arson happened at a concert in Romania.

And it wasn’t just the audience that was disciplined by authorities. In Romania, Clayton-Thomas banged a gong as part of the concert before performing “Smiling Faces” and got an enthusiastic reaction from the crowd, which began flashing peace signs with their hands and chanting, “USA! USA!” That was too “radical” for the Romanian security officials, who threatened to shut down the next concert if Clayton-Thomas did it again. The documentary shows if he and the band heeded that warning.

Tina Cunningham, an assistant to Blood, Sweat & Tears’ manager at the time, remembers in the documentary that the Romanian officials didn’t like the crowd’s reaction to the concert because it showed too much political support for the United States: “It was too much for the Romanian authorities. This was too chaotic to deal with. It was a repressed desire for freedom.”

“What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” gives wonderfully vivid descriptions in its retelling of this fateful tour. The documentary also interviews several people who were audience members at that tour. They include Aurel Mitran, Doru Stanculescu, Mike Godorja, Mircea Florian, Ion Dimandi, Jan Adamski and Krzysztof Dowgird. Kudos to the filmmakers for tracking down these fans for their much-needed perspectives.

Mitran says of his memory of the Blood Sweat & Tears concert he attended in Romania: “The feeling of freedom it exuded was extraordinary.” Gordorja, another Romanian concertgoer, says, “The Blood, Sweat & Tears concert came on like an earthquake.” Adamskie, who went saw the concert tour in Poland, remembers: “I traveled 12 hours by train to attend the concert.” Dowgird says his concert experience in Poland that it was “an event on a cosmic scale.”

“What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” gets a little bit unwieldy in the middle of the movie, when it takes a deeper dive into the history of the band. This band history breaks up the flow of the story of the tour and should have been placed near the beginning of the movie. However, the documentary gets much better in the last third, when it tells a riveting story of how Cambern’s film footage had to be smuggled out of Europe.

The documentary also responsibly shows the aftermath of what happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears after they came back home to North America. Because of the backlash against the band for doing the Iron Curtain Tour, the band’s career never again reached the same heights. Blood, Sweat & Tears would go on to break up and reunite over the years, with various lineup changes. Famous musicians getting involved in politics was not new at that time of the band’s Iron Curtain tour, but “What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” shows how mixing music and politics is a risk that can backfire if done for the wrong reasons.

Abramorama released “What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears?” in New York City on March 24, 2023, and in Los Angeles on March 31, 2023. Veeps premiered the movie for streaming on August 20, 2023.