December 9, 2023

by Carla Hay

Directed by William Oldroyd

Culture Representation: Taking place in 1964 in an unnamed city in Massachusetts, the dramatic film “Eileen” (based on the 2015 novel of the same film) features a cast of predominantly white characters (with a few African Americans) representing the working-class and middle-class.

Culture Clash: A shy administrative assistant at a juvenile detention center becomes enamored with a newly hired psychiatrist at the same job, and the two women do their own kind of pushback on what society expects from women.

Culture Audience: “Eileen” will appeal primarily to people who are fans of the movie’s headliners, the book on which the movie is based, and movies about repression and mental illness that take an unexpected turn.

Much like the movie’s namesake, “Eileen” appears to be going one way and then goes in a very different direction. The cast members’ intriguing performances are the main reason to watch this psychological drama, which takes a very dark turn near the end. The movie is weakened by a vague ending that doesn’t give the closure and answers that were given in the book.

Directed by William Oldroyd, “Eileen” is based on Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2015 novel of the same name. Moshfegh and Luke Goebel co-wrote the adapted screenplay for “Eileen.” The movie had its world premiere at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival.

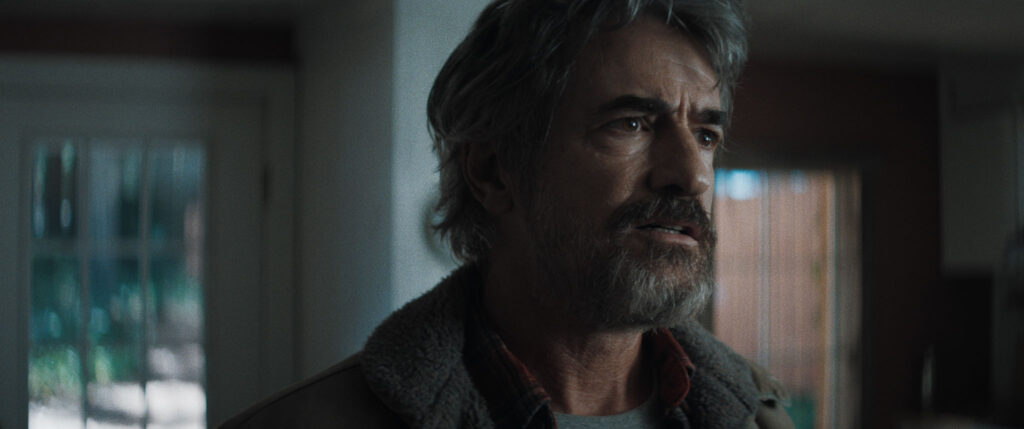

“Eileen” takes place during a bitterly cold winter in 1964, in an unnamed Massachusetts city not far from Boston. (“Eileen” was actually filmed in New York and New Jersey.) Eileen Dunlop (played by Thomasin McKenzie) is a 24-year-old bachelorette, who lives a dreary existence with her alcoholic, widower father Jim Dunlop (played by Shea Whigham), who is a former police chief. In addition to his alcoholism, there are indications that Jim has an undiagnosed mental illness.

Jim is verbally and physically abusive to Eileen, who is miserable living with her father, but she can’t afford to move out of the house. Eileen doesn’t report the abuse because she knows that Jim still has friends in the local police force. As the story goes on, it becomes clear that Eileen has a co-dependent, love/hate relationship with her father. She hates his abuse, but she also wants to feel needed, because he depends on her to take care of him.

Eileen has an older sister named Joanne, who is married and hasn’t come by to visit in quite some time. Jim tells Eileen in no uncertain terms that Joanne is his favorite child. During one of Jim’s many drunken rants, he tells Eileen that he wishes that Eileen were as organized as Joanne is. There are hints that Jim probably sexually abused Joanne as a child, which would explain why Joanne is keeping her distance from him as an adult.

For the past three or four years, Eileen has been working as a secretary/administrative assistant at Moorehead, a boys’ juvenile detention center, which is essentially a prison. It’s mentioned at one point in the movie that Eileen is a college dropout. At her job, Eileen isn’t very well-liked by the other secretaries in the office, because she’s quiet and keeps mostly to herself. Mrs. Murray (played by Siobhan Fallon Hogan) and Mrs. Stevens (played by Tonye Patano) are the two of the nosy co-workers who speak in gossipy and condescending tones to Eileen.

The beginning of the movie shows that Eileen is very introverted, but she’s not as prim and proper as she appears to the outside world. Eileen is kind of a kinky voyeur: She puts ice down her underwear after watching a couple’s makeout session. Eileen’s love life is non-existent, but she has vivid sexual fantasies about having sex with a Moorehead guard named Randy (played by Owen Teague), who’s about the same age as Eileen.

However, someone else on the job arouses Eileen’s sexual interest even more than Randy. Her name is Rebecca St. John (played by Anne Hathaway), who is Moorehead’s newly hired prison psychologist. Eileen is entranced with Rebecca from the moment that she meets this new co-worker. Rebecca, who is originally from New York City, looks and acts more like a glamorous movie star than a psychologist.

At one point, Rebecca tells Eileen that although she’s had plenty of boyfriends, she’s never been married. Rebecca says her dating relationships are “just for fun” and never last. Rebecca comes across as a progressive (she believes that psychedelic drugs should be used as therapy) and independent (she say she loves living by herself), which is the opposite of the conservative and stifling lifestyle that Eileen feels she is being pressured to live.

Eileen is infatuated with Rebecca’s sophisticated ways and seems to be fascinated with everything that Rebecca does. Rebecca notices this admiration and makes an effort to befriend Eileen, who is very flattered by the attention and the compliments that she gets from Rebecca. It’s obvious that Eileen wants her relationship with Rebecca to be more than a friendship, but does Rebecca feels the same way?

One day, Eileen notices Rebecca having a counseling session with an inmate named Lee Polk (played by Sam Nivola) and his mother, who is identified in the movie only as Mrs. Polk (played by Marin Ireland). Lee is in prison for murdering his father by stabbing him to death in the father’s bed. The father was a police officer who worked in the same police department as Eileen’s father Jim.

Eileen can see the counseling session through glass windows, but she can’t hear what’s being said behind closed doors. However, Eileen knows that the session ended badly because Mrs. Polk storms out and shouts, “Filthy, nasty boy!” Meanwhile, Lee smirks in reaction to seeing his mother upset.

Shortly after the session ends, Rebecca asks Eileen if she thinks Mrs. Polk is an angry woman. Eileen doesn’t know enough about Mrs. Polk to give an opinion either way. However, Eileen tells Rebecca that she thinks Lee is intelligent and that he doesn’t seem like the type to be a cold-blooded murderer.

A turning point in Eileen’s relationship with Rebecca happens when Rebecca asks Eileen to go with her to a local bar. Rebecca says it’s because she’s new to the area and wants to meet more new people. But as far as Eileen is concerned (based on how excitedly she gets ready for this meet-up), Rebecca has asked her on a date. At the bar, Rebecca will only dance with Eileen and literally shoves a man away who tries to cut in on Rebecca and Eileen dancing together.

One of the strengths of “Eileen” is how all of the principal cast members make their characters very believable. Even when not much is happening in certain scenes, the performances of McKenzie and Hathaway make viewers wonder what Eileen and Rebecca might be really thinking, compared to what they’re saying out loud. That’s an example of the compelling acting in this movie.

Viewers who don’t know what’s in the “Eileen” book or don’t know what happens in the last third of the movie probably won’t see the plot twist coming. The “Eileen” book is told from the perspective of a middle-aged Eileen looking back on her life. The “Eileen” movie does not give that retrospective context and therefore brings up questions that remain unanswered by the end of the film. However, the movie has an impeccable buildup to its most suspenseful moments, even if the ending won’t be as satisfying as some viewers hope it will be.

Neon released “Eileen” in select U.S. cinemas on December 1, 2023, with an expansion to more U.S. cinemas on December 8, 2023.