July 28, 2020

by Carla Hay

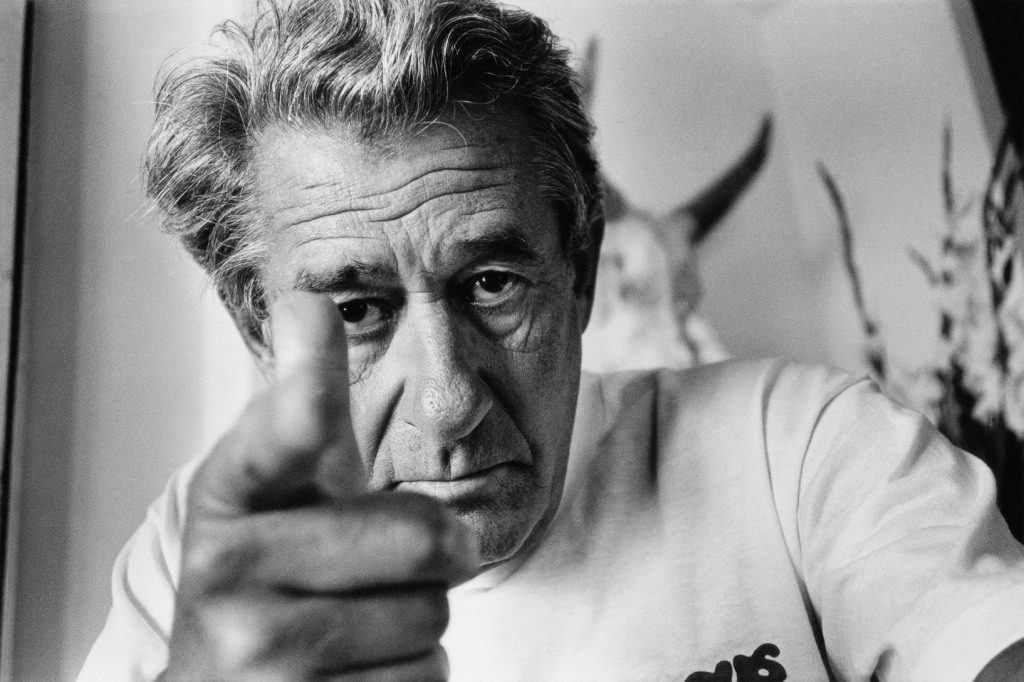

“Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful”

Directed by Gero Von Boehm

Culture Representation: This documentary about famed German fashion photographer Helmut Newton interviews a nearly all-white, predominantly European group of people who were his business associates or close confidants.

Culture Clash: People often debate if some of Newton’s photos are “edgy” or “offensive,” and he was frequently accused of being sexist and misogynistic.

Culture Audience: “Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful” will appeal primarily to people interested in fashion photography from the late 20th century.

Famed fashion photographer Helmut Newton, who died in 2004 at the age of 83, had the nickname King of Kink, so would his career have survived the #MeToo movement? And how would he have handled social media, where celebrities and models can create and show their own portfolio of photos to the world? These are interesting questions to think about when watching the fascinating and at times too-reverential documentary “Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful,” which chronicles the life of Newton, who had a reputation for being the German “bad boy” of fashion photography.

His death (he passed away in a car accident in Los Angeles) came years before the #MeToo movement and social media existed. And based on what’s presented in “Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful” (directed by Gero Von Boehm), an “old school” famous fashion photographer such as Newton might have had a difficult time adjusting to the #MeToo movement and social-media era, when sexually aggressive behavior in the workplace is less tolerated and celebrity selfies on Instagram have diluted the gatekeeper influence of A-list fashion photographers.

The greatest strength of the documentary is the access to archival video footage and photos from the Helmut Newton Foundation. They tell more about Newton in ways that no amount of interviews with “talking heads” would be able to tell. According to the documentary’s production notes, director Von Boehm met Helmut Newton in 1997, and stayed in touch with him and his wife June Newton (also known as photographer Alice Springs) over the years and filmed approved segments of Helmut’s life.

June (an Australian model/actress who married Helmut in 1948) is interviewed for the documentary. She does not appear on camera for these interviews, but is heard in voiceovers. June is seen in archival “home movie” type of footage and in photos. The couple did not have any children.

In the documentary’s production notes, Von Boehm says of the first time that he met Helmut: “We understood each other right away and discovered we had a very similar sense of humor, the same sense for bizarre situations.” But even if Von Boehm had not admitted this bias up front, it’s clear from watching the documentary that it was made by a director who has immense admiration for Helmut.

However, that worshipful attitude clouds this documentary’s perspective to the point where Helmut’s boorish ways are constantly excused in the documentary as Helmut just being Helmut, without giving any proper acknowledgement or context of the people he hurt along the way because he abused his power. For example, he had a reputation for pressuring female models to pose nude for him, but male models weren’t subjected to the same type of browbeating.

If it were really about “art” and celebrating the human body, and not sexism, then he wouldn’t have an obviously singular obsession with having so many naked women in his photos. And when his photos depicted degrading scenarios (such as bondage or being physically attacked), the targets of this degradation were women, not men.

Helmut had a reputation in the fashion industry for being a “dirty old man,” which is a reputation that he seemed to be proud of embracing, at a time when A-list fashion photographers (who are almost always men) could get away with a lot more in mistreating models than they can now. Some of the people interviewed in the film have a type of misguided snobbery that enables misogyny if it comes from someone famous or someone who can benefit them in some way.

Speaking of the people interviewed in the documentary, perhaps to offset the inevitable criticism of Helmut having a reputation for being sexist against women, director Von Boehm made the decision to have only women interviewed for the film. Not surprisingly, all of them praise Helmut. Do you really think that the filmmakers would want to include any women who were going to talk about their unpleasant experiences with Helmut? Of course not.

The interviewees include Vogue (U.S.) editor-in-chief/Condé Nast artistic director Anna Wintour, Vogue executive fashion editor Phyllis Posnick and gallerist Carla Sozzani, a close friend of Helmut and June Newton. The other women interviewed are mostly models or entertainers who were photographed by Helmut for fashion spreads, such as Isabella Rossellini, Charlotte Rampling, Claudia Schiffer, Marianne Faithfull, Grace Jones, Nadja Auermann, Sylvia Gobbel and Arja Toyryla.

Helmut’s family background and early career aren’t described until halfway through the movie. Born in Berlin in 1920, Helmut (whose birth surname was Neustädter) grew up Jewish in Germany under the Weimar Republic (which existed from 1918 to 1933), where he was surrounded by images and beliefs that white Aryans (light-skinned, non-Jewish Caucasians descended from most of Europe) are superior to all other people.

It’s not outrightly stated, but it’s pretty clear from interviews and how Helmut expressed himself in his work that this indoctrination of Aryan supremacy led to him having a lifelong inferiority complex about being Jewish in an Aryan world. Several people, including Helmut, say in that the documentary that this complex carried over into his fixation on what Helmut considered his ideal type of female model: tall, thin and Aryan-looking, preferably blonde.

Helmut’s mother Klara “Claire” (whom he describes as being “spoiled” with a strong personality) encouraged his interest in photography, while his father Max (who owned a button factory) disapproved because he didn’t think being a photographer was a “real” job. A recurring theme in Helmut’s life is that he was attracted to strong, beautiful women, but he also feared them. Given that Helmut’s mother is described as domineering, a Freudian psychiatrist would have a field day with giving an analysis of how Helmut’s complicated views of women affected his art.

In the documentary, Helmut says one of his earliest artistic influences was German director Leni Riefenstahl, who filmed a lot of Nazi propaganda under the Adolf Hitler regime. He describes Austrian American director Erich von Stroheim as “one of my heroes.” And it’s mentioned several times in the documentary that Helmut maintained a lifelong love of Berlin and the city’s artists.

Helmut’s first photography mentor was Yva, the alias of Else Ernestine Neuländer-Simon, a German Jewish photographer whom he worked with as an apprentice for two years. Helmut says of his apprenticeship with Yva: “It was wonderful. I worshipped the ground she walked on.” (Yva tragically died in a Nazi concentration camp around 1942.)

Even as a teenager, Helmut had a rebellious side. In one of the documentary interviews, he remembers going to a public swimming pool where Jews weren’t allowed, and he stripped a girl naked in the pool. (He says the girl allowed him to do it.) This brazen act got him banned from the pool, but Helmut still cackles with glee when he tells the story decades later. As for his controversial image as a photographer, Helmut once famously said that he considered “art” and “good taste” to be bad words in photography.

His wife June is described as his authoritative partner and constant companion who was in charge of a lot of Helmut’s business interests. June says of Helmut: “He was always a naughty boy, who grew up to be an anarchist.” There’s some archival footage of Helmut at a photo shoot in the 1980s where he jubilantly says to the camera that he just made $10,000 for the photo shoot, and it’ll be money that he’ll spend buying diamonds “for my Junie.”

The documentary includes rare footage of Helmut inside one of his and June’s homes, where he gives a brief tour for the people filming the footage. The interior décor can best be described as “kitschy” and “gaudy,” cluttered with a lot of trinkets and knickknacks. They also had several Barbie dolls on display. It’s in stark contrast to the sleek, sophisticated-looking and artsy photos that Helmut was known to take.

And what do some of Helmut’s former photo subjects have to say about him?

Italian-born actress Rossellini worked with Helmut for the first time in 1986, when Helmut did a photo shoot with Rossellini and director David Lynch to promote the movie “Blue Velvet.” She comments that Helmut “represents men who are attracted to women, but then resent [women] because they’re attracted to them, so they make [women] vulnerable.”

French actress Rampling, who posed for Helmut’s first major nude photo shoot in 1973, says of his often-controversial reputation: “It’s great to be a provocateur. That’s what the world needs. Who cares about the man himself? We’re looking at his art.” Rampling also says that art is not meant to be objective and looked at in the same way by all people: “There is no neutrality. Everything is tainted with a point of view.”

German model/actress Gobbel comments that being a tall, blonde woman in her modeling days often made her feel like “a hunted deer,” but she says that being photographed by Helmut made her feel “stronger.” Finnish model Toyryla echoes a similar thought, by saying of her experience working with Helmut: “I just looked into his eyes, and I knew what he wanted. It felt good. I felt safe.” German actress/singer Schygulla says, “I found him amusing, this mix of ease and humor, but also obsession.”

British singer/actress Faithfull worked with Helmut in the 1980s. One of her more well-known photo shoots with Helmut resulted in a famous set of 1981 Esquire magazine photos of her wearing a leather jacket, with nothing on underneath the jacket: “Helmut made me show my tits without [me] feeling any embarrassment or shame.” (The photos are actually very tame, since her nipples aren’t showing.)

German former supermodel Schiffer, who did several non-nude photo shoots with Newton, worked with him for the first time when she was 17. She describes the experience this way: “There was never a moment when I felt uncomfortable. It was an amazing experience, where I walked away saying, ‘This man is incredible.’ He had sort of a twinkle in his eyes.”

Schiffer also describes a Helmut Newton photo shoot where a very young and inexperienced female model showed up, not knowing that she would have to pose in a dominant/submissive scenario. In the photo shoot, the newbie model was dressed as a maid, while Schiffer portrayed the maid’s rich employer. In one of the photos (which is seen in the documentary), Schiffer is standing over the kneeling “maid” while forcing her head into an oven. According to Schiffer, the other model was very nervous at first, but they all ended up having a laugh over it.

Auermann, another German former supermodel, says that “Helmut actually really loved strong women.” However, she admits that because she didn’t give in to his constant pressure to pose nude for him, she didn’t work with him for two years. Auermann was a model for two of Helmut’s most controversial photo spreads.

In (U.S.) Vogue’s June 1994 issue, Aeurmann did a Helmut Newton photo shoot where they recreated the Greek myth “Leda and the Swan,” and it caused outrage because Auermann was posed with the swan (which was a taxidermy animal) in a sexually suggestive way. She says that people sent a lot of hate mail because of that photo shoot, which critics said looked like it was promoting bestiality and animal cruelty. Auermann believes that people would have been less offended if they knew that the swan used in the photo shoot was actually a stuffed animal.

The January 1995 issue of (U.S.) Vogue featured Helmut Newton photos of Auermann posed as a person with leg disabilities, such as being in a wheelchair, using crutches and wearing leg braces. In one photo, using visual effects, it looks like she has one leg, while her “missing” leg is detached and posed upright next to her. In the documentary, Auermann (who is able-bodied in real life) remembers the public reaction being a “shitstorm” because people thought that the photos were making a mockery of disabled people.

Jamaican singer/actress Jones is one of the few people of color who was asked to do a Helmut Newton photo shoot. Jones had her own controversial set of photos with him in the 1980s, when she usually posed completely nude for him. A semi-erotic 1985 photo shoot that Jones and Dolph Lundgren (her lover at the time) did for Playboy magazine caused a little bit of a stir with people who were uncomfortable with seeing a naked interracial couple in provocative poses.

But those photos weren’t as nearly as controversial as a Helmut Newton photo on the cover of Stern magazine (a German publication) that had Jones posed naked, with chains on her legs, conjuring up an image that made her look like a slave. Jones dismisses the “slave image” controversy in the documentary and says, “I really wasn’t aware that it made such a big scandal. I kind of heard around a bit of [accusations of] sexism and racism, but I never felt that at all. I mean, it’s like acting in films.”

Jones admits that she thought Helmut was like a “god” and she jumped at the chance to work with him. But she also says that Helmut had a weird habit of asking to do a photo shoot with her and then sending her away because he remembered that she was flat-chested and he wanted to shoot models with bigger breasts.

Jones says she didn’t take offense because she thought of him as an eccentric. “He was a little bit of a pervert, but so am I, so that’s okay,” Jones comments. “His pictures were erotic, but with dimensions … They told stories.”

Vogue’s Wintour (who worked with Helmut for many years) says in the documentary, “If you were to give an assignment to Helmut, you weren’t going to receive a pretty girl on a lovely beach. That’s not what he was about.” She adds that Vogue expected that photos from him would be “iconic, sometimes disturbing, certainly thought-provoking … You might consider it brave, but I would consider it necessary.” She says that his photos were needed as a counterpoint to the overly glamorous, fantasy-level type of photos that proliferate in fashion.

And his fashion photography wasn’t always about humans. Posnick remembers Helmut being ecstatic when Vogue gave him an assignment to do a photo shoot featuring his favorite animals: chickens. There was his famous 1994 “Roast Chicken and Bulgari Jewels” photo spread for Vogue, showing a roasted chicken being cut with a large knife by a woman’s hands wearing Bulgari jewelry.

He told the Vogue editors that he always wanted to photograph chickens wearing high heels. And so, in 1998, Vogue flew in some high heels from a doll museum in Monte Carlo so that Helmut could do a photo called “Chicken in Heels,” which showed a cooked chicken wearing the high-heeled doll shoes. When a photographer is indulged in this over-the-top way, is it any wonder that this person would be on an egotistical power trip?

There’s some archival footage in the documentary that looks like it was filmed sometime in the late 1980s or early 1990s, where Helmut is doing a photo shoot with a female model in a skimpy swimsuit and a male model wearing scuba-fiving gear. He jokes to the male model, “If you get a hard-on, you’ll get more money.” Helmut then adds, presumably talking about Wintour: “I’m going to send this to Anna. She’ll have a fit.”

For all this talk about Helmut being a “provocateur” and “edgy,” apparently something that was too much out of his comfort zone was working with a racially diverse group of models. Jones, one of the few black women he photographed, was already a celebrity when she began working with him. But women of color, even if they were famous models, apparently had little to no chance of working with him. The documentary includes rare footage of a casting call that Newton did sometime in the 1980s, and all of the models are white—which probably means that modeling agencies already knew not to bother sending any non-white women to this casting call.

The documentary makes it clear that Helmut had a certain type of model that he preferred (tall, thin and Aryan-looking), but nowhere does the documentary address the race issue and why he didn’t seem very open to working with non-white models. It speaks to a larger culture of race exclusion in an industry where Vogue magazine, which launched in 1892, didn’t hire a black photographer to shoot a Vogue cover until Beyoncé was given unprecedented complete creative control for her 2018 (U.S.) Vogue cover shoot. (In June 2020, Wintour publicly admitted that Vogue has had racism problems for many years, and she made an apology, with a vague promise to improve Vogue’s race relations with people of color.)

Also noticeably omitted from the documentary is any discussion about drug use, which is rampant in the fashion industry. And as for infidelity, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Helmut, whose job was taking photos of a lot of beautiful women (many of them naked), wasn’t exactly a faithful husband, although he and June stayed married for about 56 years.

Family friend Sozzani explains Helmut and June Newton’s relationship, by saying that there was infidelity on both sides, but nothing that was serious enough to ruin their marriage: “I think they were everything together. This is the dream of every couple in life, to have met your perfect person that you respect, that you can build something together. It’s wonderful.” Sozzani adds, “They had difficult times, like every couple,” as she describes with a chuckle how furious Helmut was when he caught June in a hotel with another man.

Cameras and taking photos were such an obsession for June and Helmut that the documentary includes photos that they took of each other in hospitals after having surgery and showing their surgery scars. June comments, “The only thing that kept him going was the little camera by his side. Yes, it is a protection … He even took it into the operating room.”

And there’s a morbid photo included at the end of the film that June took of herself holding Helmut’s head in her arms, right after his fatal car accident. It’s unclear if he’s dead or unconscious in the photo, but it’s implied that June knew that it would be the last photo she would take of him.

Because so much of the documentary is a praise-fest of Helmut, the only voice of criticism comes from a 1970s clip from a TV talk show where he and feminist Susan Sontag were guests. Sontag tells him she’s not a fan of his work because his photos are often misogynistic, while Helmut objects to that opinion and says that he actually loves women.

An unflappable Sontag replies that misogynists often claim that they love women, but then still show women in a humiliating way. She then shuts down Helmut by saying, “The master loves his slave. The executioner loves his victim.”

The documentary also includes an audio clip from an interview Helmut did (it’s unclear if he made this comment for the documentary or if it’s from an outside interview) where he makes a very telling comment. Helmut comes right out and admits that he doesn’t really care about the models he works with, and that he just cares about how they photograph when he takes their pictures.

Although the documentary doesn’t offer any new interviews with any critics of Helmut, there’s no doubt that he made a lot of memorable art, whether people were fans of his or not. Most of his photos were not degrading to women, and there are many interesting visuals in the documentary that put into context why Helmut was attracted to making this kind of art. (However, people who have a problem with seeing a lot of naked people in photos will probably want to skip watching this film.)

Was he sexist? Was he racist? “Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful” doesn’t seem to want to answer those questions, but there’s enough of a compelling story here, so people can judge for themselves whether or not they want to separate the man from his art.

Kino Lorber released “Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful” in select U.S. virtual cinemas on July 24, 2020.