November 14, 2021

by Carla Hay

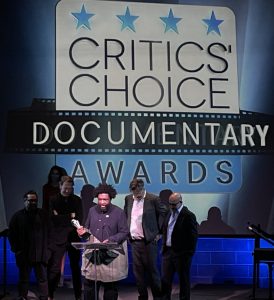

With six awards, including Best Documentary Feature, Searchlight Pictures’ “Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)” was the top winner for the sixth annual Critics Choice Documentary Awards. The winners were announced during a ceremony hosted by comedian Roy Wood Jr. at BRIC in Brooklyn, New York, on November 14, 2021. The Critics Choice Association, a group of more than 500 movie and TV critics, presents and votes for the awards. Eligible documentaries for the 2021 Critics Choice Awards were documentaries with U.S. release dates in 2021.

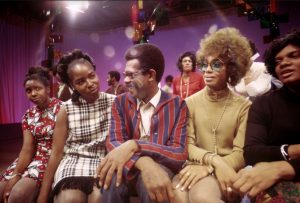

“Summer of Soul,” which includes long-lost footage of the 1969 all-star Harlem Cultural Festival, is the feature-film directorial debut of Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, who also won the prizes for Best Director and Best First Documentary Feature. “Summer of Soul” also took the prizes for Best Music Documentary, Best Archival Documentary and Best Editing, thereby winning awards in all of the categories for which it was nominated.

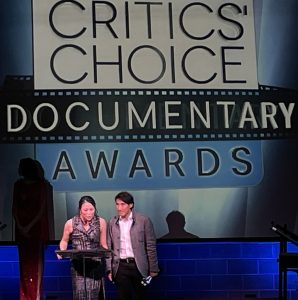

National Geographic Documentary Films’ “The Rescue,” about the 2018 rescue of a group of young soccer players and their coach who were trapped in a Thailand cave, won three Critics Choice Documentary Awards: Best Director for Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin (who won the prize in a tie with “Summer of Soul” director Thompson); Best Cinematography; and Best Score. “The Rescue” has also been an award winner at a major film festival, having received the Best Documentary Feature prize at the 2021 Toronto International Film Festival.

Val Kilmer’s autobiographical documentary “Val” (from Amazon Studios) took the prizes for Best Historical or Biographical Documentary. Other winning documentaries were Roadside Attractions’ “The Alpinist” (Best Sports Documentary); HBO’s “The Crime of the Century” (Best Political Documentary); National Geographic Documentary Films’ “Becoming Cousteau” (Best Science/Nature Documentary) and The New York Times’ “The Queen of Basketball” (Best Short Documentary).

“Ascension,” director Jessica Kingdon’s documentary about consumerism in China, was tied with “Summer of Soul” with the most nominations (six each) for the 2021 Critics Choice Documentary Awards. However, “Ascension” (distributed by MTV Documentary Films) did not win any of the Critics Choice Documentary Awards for which the documentary was nominated. Also missing out on winning prizes, after getting several nominations, were Amazon Studios’ “I Am Pauli Murray” (directed by Julie Cohen and Betsy West); Showtime’s “Attica” (directed by Stanley Nelson and Traci A. Curry); and Apple TV+’s “The Velvet Underground” (directed by Todd Haynes).

“Summer of Soul” has been on a hot streak, ever since it won the Grand Jury Prize and Audience Award in the U.S. Documentary Competition at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, where the movie had its world premiere. “Summer of Soul” has the added benefit of being a triumphant story about a documentary that took 52 years to finally be released to the public. A documentary about the Harlem Cultural Festival (which featured major stars such as Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Sly and the Family Stone, B.B. King and Gladys Knight and the Pips) had been pitched to movie studios and TV networks, ever since the festival took place in 1969, but it was rejected for decades.

The unedited footage stayed in the possession of director/producer Hal Tulcin, who directed the footage that was filmed of the Harlem Cultural Festival. Before he died in 2017, at the age of 90, Tulchin signed over the rights to the footage to “Summer of Soul” producers Robert Fyvolent and David Dinerstein, who then hired Thompson to direct an edited film. Thompson is also known as a DJ, as the drummer for The Roots and as the band leader for “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon.” “Summer of Soul” was released in select U.S. cinemas on June 25, 2021, and expanded to more theaters and premiered on Hulu on July 2, 2021. In addition to the archival footage, “Summer of Soul” has new and exclusive interviews with some of the festival’s artists and audience members, as well as cultural commentators.

During his multiple trips to the podium to accept awards for “Summer of Soul,” Thompson said he felt overwhelmed with excitement and gratitude. “This is the best night of my life!” he declared at one point. He thanked his entire filmmaking team, as well as Searchlight Pictures, Hulu, Tulchin and the festival artists for making the documentary happen.

Longtime documentarian R.J. Cutler received the Pennebaker Award (formerly known as the Critics Choice Lifetime Achievement Award). This award is named for Critics Choice Lifetime Achievement Award winner D.A. Pennebaker, who died in 2019. The award was presented to Cutler by Chris Hegedus, who is Pennebaker’s producing partner and wife. Cutler thanked many of his colleagues and loved ones, including his daughter Penny, who he said was born six months ago and was named after Pennebaker.

The evening had some moments of levity, particularly from ceremony host Wood. When he kept commenting on Thompson’s unique fashion sense, Thompson took off his jacket and put it on Wood. (It was an unscripted moment.) Many of the presenters (which included documentarian Barbara Kopple, “Summer of Soul” director Thompson and actress Piper Perabo) commented on the high quality of documentaries that were released this year. Dana Delany said that she can’t stop talking about the Showtime documentary “Attica,” which is a chronicle of the 1971 uprising at Attica Prison in New York state.

This year, the Critics Choice Documentary Awards had its first presenting sponsor: National Geographic Documentary Films.

Here is the complete list of nominees and winners for the 2021 Critics Choice Documentary Awards:

*=winner

BEST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE

- Ascension (MTV Documentary Films)

- Attica (Showtime)

- Becoming Cousteau (Picturehouse/National Geographic Documentary Films)

- The Crime of the Century (HBO Documentary Films)

- A Crime on the Bayou (Augusta Films/Shout! Studios)

- Flee (Neon)

- Introducing, Selma Blair (Discovery+)

- The Lost Leonardo (Sony Pictures Classics)

- My Name is Pauli Murray (Amazon Studios)

- Procession (Netflix)

- The Rescue (National Geographic Documentary Films)

- Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Searchlight Pictures/Hulu)*

BEST DIRECTOR

- Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin – The Rescue (National Geographic Documentary Films)* (tie)

- Liz Garbus – Becoming Cousteau (Picturehouse/National Geographic Documentary Films)

- Jessica Kingdon – Ascension (MTV Documentary Films)

- Stanley Nelson and Traci A. Curry – Attica (Showtime)

- Jonas Poher Rasmussen – Flee (Neon)

- Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson – Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Searchlight Pictures/Hulu)* (tie)

- Edgar Wright – The Sparks Brothers (Focus Features)

BEST FIRST DOCUMENTARY FEATURE

- Jessica Beshir – Faya Dayi (Janus Films)

- Rachel Fleit – Introducing, Selma Blair (Discovery+)

- Todd Haynes – The Velvet Underground (Apple TV+)

- Jessica Kingdon – Ascension (MTV Documentary Films)

- Kristine Stolakis – Pray Away (Netflix)

- Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson – Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Searchlight Pictures/Hulu)*

- Edgar Wright – The Sparks Brothers (Focus Features)

BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY

- Jessica Beshir – Faya Dayi (Janus Films)

- Jonathan Griffith, Brett Lowell and Austin Siadak – The Alpinist (Roadside Attractions)

- David Katznelson, Ian Seabrook and Picha Srisansanee – The Rescue (National Geographic Documentary Films)*

- Jessica Kingdon and Nathan Truesdell – Ascension (MTV Documentary Films)

- Nelson Hume and Alan Jacobsen – The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52 (Bleecker Street Media)

- Emiliano Villanueva – A Cop Movie (Netflix)

- Pete West – Puff: Wonders of the Reef (Netflix)

BEST EDITING

- Francisco Bello, Matthew Heineman, Gabriel Rhodes and David Zieff – The First Wave (National Geographic Documentary Films)

- Jeff Consiglio – LFG (HBO Max and CNN Films)

- Bob Eisenhardt – The Rescue (National Geographic Documentary Films)

- Affonso Gonçalves and Adam Kurnitz – The Velvet Underground (Apple TV+)

- Jessica Kingdon – Ascension (MTV Documentary Films)

- Joshua L. Pearson – Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Searchlight Pictures/Hulu)*

- Julian Quantrill – The Real Charlie Chaplin (Showtime)

BEST NARRATION

- 9/11: Inside the President’s War Room (Apple TV+)/Jeff Daniels, Narrator

- Becoming Cousteau (Picturehouse/National Geographic Documentary Films)/Vincent Cassel, Narrator; Mark Monroe and Pax Wassermann, Writers

- The Crime of the Century (HBO Documentary Films)/ Alex Gibney, Narrator; Alex Gibney, Writer

- The Neutral Ground (PBS)/CJ Hunt, Narrator; CJ Hunt, Writer

- The Real Charlie Chaplin (Showtime); Pearl Mackie, Narrator; Oliver Kindeberg, Peter Middleton and James Spinney, Writers

- Val (Amazon Studios); Jack Kilmer, Narrator; Val Kilmer, Writer*

- The Year Earth Changed (Apple TV+)/David Attenborough, Narrator

BEST SCORE

- Jongnic Bontemps – My Name is Pauli Murray (Amazon Studios)

- Dan Deacon – Ascension (MTV Documentary Films)

- Alex Lasarenko and David Little – The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52 (Bleecker Street Media)

- Cyrus Melchor – LFG (HBO/CNN)

- Daniel Pemberton – The Rescue (National Geographic Documentary Films)*

- Rachel Portman – Julia (Sony Pictures Classics)

- Dirac Sea – Final Account (Focus Features)

BEST ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTARY

- Becoming Cousteau (Picturehouse/National Geographic Documentary Films)

- The Real Charlie Chaplin (Showtime)

- The Real Right Stuff (Disney+)

- Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street (HBO Documentary Films)

- Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Searchlight Pictures/Hulu)*

- Val (Amazon Studios)

- The Velvet Underground (Apple TV+)

BEST HISTORICAL OR BIOGRAPHICAL DOCUMENTARY

- Attica (Showtime)

- A Crime on the Bayou (Augusta Films/Shout! Studios)

- Fauci (Magnolia Pictures/National Geographic Documentary Films)

- Final Account (Focus Features)

- Julia (Sony Pictures Classics)

- My Name is Pauli Murray (Amazon Studios)

- No Ordinary Man (Oscilloscope)

- Val (Amazon Studios)*

BEST MUSIC DOCUMENTARY

- Billie Eilish: The World’s A Little Blurry (Apple TV+)

- Bitchin’: The Sound and Fury of Rick James (Showtime)

- Listening to Kenny G (HBO Documentary Films)

- The Sparks Brothers (Focus Features)

- Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (Searchlight Pictures/Hulu)*

- Tina (HBO Documentary Films)

- The Velvet Underground (Apple TV+)

BEST POLITICAL DOCUMENTARY

- The Crime of the Century (HBO Documentary Films)*

- Enemies of the State (IFC Films)

- Four Hours at the Capitol (HBO Documentary Films)

- Influence (StoryScope, EyeSteelFilm)

- Mayor Pete (Amazon Studios)

- Missing in Brooks County (Giant Pictures)

- Nasrin (Hulu)

- Not Going Quietly (Greenwich Entertainment)

BEST SCIENCE/NATURE DOCUMENTARY

- Becoming Cousteau (Picturehouse/National Geographic Documentary Films)*

- Fauci (National Geographic Documentary Films)

- The First Wave (National Geographic Documentary Films)

- The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52 (Bleecker Street Media)

- Playing with Sharks (National Geographic Documentary Films)

- Puff: Wonders of the Reef (Netflix)

- The Year Earth Changed (Apple TV+)

BEST SPORTS DOCUMENTARY

- The Alpinist (Roadside Attractions)*

- Changing the Game (Hulu)

- The Day Sports Stood Still (HBO)

- Kevin Garnett: Anything is Possible (Showtime)

- LFG (HBO Max/CNN Films)

- Tiger (HBO)

BEST SHORT DOCUMENTARY

- Audible (Netflix)

- Borat’s American Lockdown (Amazon Studios)

- Camp Confidential: America’s Secret Nazis (Netflix)

- Day of Rage: How Trump Supporters Took the U.S. Capitol (The New York Times)

- The Doll (Jumping Ibex)

- The Last Cruise (HBO Documentary Films)

- The Queen of Basketball (The New York Times)*

- Snowy (TIME Studios)

Non-Competitive Categories

MOST COMPELLING LIVING SUBJECTS OF A DOCUMENTARY (ALL HONOREES)

- Ady Barkan – Not Going Quietly (Greenwich Entertainment)

- Selma Blair – Introducing, Selma Blair (Discovery+)

- Pete Buttigieg – Mayor Pete (Amazon Studios)

- Anthony Fauci – Fauci (Magnolia Pictures/National Geographic Documentary Films)

- Ben Fong-Torres – Like a Rolling Stone: The Life and Times of Ben Fong-Torres (StudioLA.TV)

- Val Kilmer – Val (Amazon Studios)

- Ron and Russell Mael – The Sparks Brothers (Focus Features)

- Rita Moreno – Rita Moreno: Just a Girl Who Decided to Go For It (Roadside Attractions)

- Valerie Taylor – Playing With Sharks: The Valerie Taylor Story (Disney+)

PENNEBAKER AWARD

- R.J. Cutler