September 18, 2020

by Carla Hay

Directed by Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz

Culture Representation: Taking place in various parts of the American South, the horror film “Antebellum” has a cast of African American and white people representing the middle-class and working-class.

Culture Clash: The world of a successful, modern-day African American woman is somehow linked to a Southern plantation where she and other African Americans are mistreated and abused as slaves.

Culture Audience: “Antebellum” will appeal primarily to people who might think that a horror movie about the brutality of slavery would have some insightful social commentary, but the horrific abuse in the film is mostly exploitation.

You can almost hear the gimmick pitch that got “Antebellum” made into a movie: “Let’s make a horror film that’s like ’12 Years a Slave’ meets ‘Get Out.'” Unfortunately, “Antebellum” is nowhere near the quality or merit of the Oscar-winning “12 Years a Slave” and “Get Out,” even though QC Entertainment (one of the production companies behind “Get Out”) is a production company for “Antebellum.”

The sad reality is that “Antebellum” just seems like an exploitative cash grab to attract Black Lives Matter supporters, but the movie is really a “bait and switch,” because there’s almost no social consciousness in the movie and nothing to be learned from the story. “Antebellum” is actually a very soulless and nonsensical horror flick that uses slavery as a way to just have repetitive scenes of African Americans being sadistically beaten, strangled and raped.

Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz, who have a background in directing commercials, co-wrote and co-directed “Antebellum,” which is their feature-film debut. Normally, it’s not necessary to mention the race of a filmmaker when reviewing a movie. But because “Antebellum” is about the triggering and controversial topics of racism, slavery and the exploitation of African Americans, it should be noted that Bush is African American and Renz is white.

Just because an African American co-wrote and co-directed this movie doesn’t excuse the problematic way that racist violence against African Americans is depicted in the movie. “Antebellum” has this racist violence for violence’s sake, with little regard to making any of the slaves, except for the movie’s main character, have any real substance. It’s the equivalent of a mindless slasher film that doesn’t care about having a good plot or well-rounded characters but just takes perverse pleasure in seeing how the victims get attacked, tortured and possibly killed.

The movie doesn’t waste any time showing this cruel violence, since the opening scene is of a male slave named Eli (played by Tongayi Chirisa) being separated from his love partner/wife named Amara (played by Achok Majak) by a group of plantation supervisors in Confederate military uniforms. The group is led by the evil racist Captain Jasper (played by Jack Huston), who takes pleasure in torturing Amara, who is lassoed with a rope around the neck when she tries to run away in the cotton field. You can easily guess what happens next.

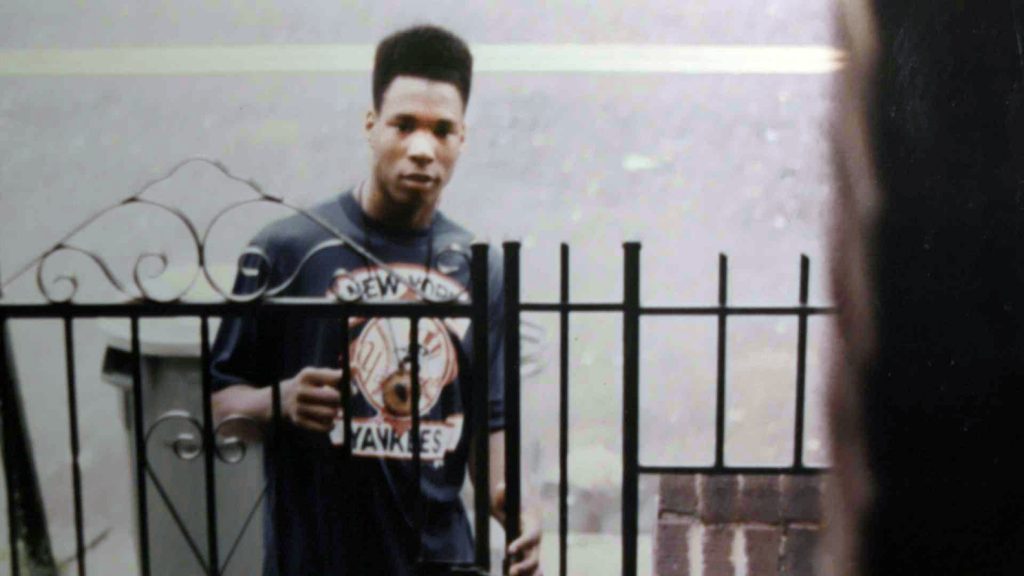

People who’ve seen any “Antebellum” trailers or clips might wonder why the movie’s protagonist (played by Janelle Monáe) seems to be in two different worlds: In one world, she’s a slave on a plantation during the Civil War era. In another world, she’s a present-day, happily married mother of a young daughter.

To explain why she exists in these two worlds would be a major spoiler for the movie. But it’s enough to say that the explanation comes about halfway through the film, and it creates questions that are never really answered by the end of the movie. “Antebellum” is supposed to take place in different unnamed cities in the South. The movie was actually filmed in New Orleans.

In the plantation world, Monáe is a quietly defiant slave who is secretly planning to escape with some other slaves. She has been named Eden by the plantation’s sadistic owner who goes by the name “Him” (played by Eric Lange), who assaults her and burns her with a hot branding iron until she agrees that her name is Eden. Later, he rapes her. The real name of “Him” is revealed later in the movie.

We don’t see Eden do much plotting to escape in the movie, mainly because the slaves have been ordered not to talk to each other or else they will be punished. It’s implied that Eden is the self-appointed leader of this escape plan because another slave named Julia (played by Kiersey Clemons) arrives at the plantation and expects Eden to fill her in on the escape details.

Julia, who is pregnant, tells Eden that she heard that Eden is from Virginia. Julia says that she’s from North Carolina. Eden replies, “Wherever you came from before here, you need to forget North Carolina.” Julia says, “That’s not possible for me. What are we doing? What’s the plan?” Eden responds, “We must choose are own wisely. But until then, we must keep our heads down and our mouths shut.”

Later, when Julia becomes frustrated by what she thinks is Eden stalling or not doing anything to implement the escape plan, she angrily says to Eden: “You ain’t no leader. You’re just a talker.” And since Julia is pregnant, you can bet her pregnancy will be used as a reason to make any violence against her more heinous.

Meanwhile, Captain Jasper has an equally racist wife named Elizabeth (played by Jena Malone), who is as ice-cold as her husband is quick-tempered. It’s implied, but not said outright, that she knows he rapes the female slaves. In an early scene in the movie, Elizabeth recoils when Jasper leans in to kiss her. She sniffs, as if to smell him, and says with a slightly disgusted tone, “Hmm. You started early.”

Meanwhile, the modern-day character played by Monáe is a sociologist and best-selling author named Veronica Henley, whose specialty is in social justice issues related to race. And in this story, she’s promoting her book “Shedding the Coping Persona,” which is about marginalized people learning to be their authentic selves instead of pretending to be something they’re not to please their oppressors. Veronica is well-educated (she has a Ph. D. and is a graduate of Spelman College and Columbia University) and she’s happily married. She’s prominent enough to have debates on national TV about topics such as racism and African American empowerment.

Veronica and her husband Nick (played by Marque Richardson) have an adorable daughter who’s about 5 or 6 years old named Kennedi (played by London Boyce), who’s very inquisitive and perceptive. After the family watches a debate-styled interview that Veronica did on TV with a conservative white male pundit (whose profession is listed “eugenics expert/professor”), Kennedi asks Veronica why the man was so angry. Veronica replies, “Sometimes what looks like anger is really just fear.”

Nick is the type of doting husband and father who will make breakfast for Veronica and Kennedi. Meanwhile, Veronica confides in her sassy single friend Dawn (played by Gabourey Sidibe) that she often feels guilty about being away from home when she has to work. Dawn reassures Veronica that she’s a great wife and mother and tells Veronica not to be too hard on herself. (Dawn, who is assertive and outspoken, has some of the best and funniest lines in the movie.)

Veronica has to go out of town to attend an African American-oriented conference called VETA, where she is a guest speaker. Dawn lives in the area, so they make plans to have dinner with Dawn’s friend Sarah (played by Lily Cowles), who is also single and available. Before Veronica meets up with them, she gets a bouquet of flowers delivered to her at her hotel. The flowers have a note that says, “Look forward to your homecoming.”

Veronica assumes that the gift is from Nick. But since this is a horror movie, viewers can easily figure out that Nick did not send those flowers. Some other strange things happen in the hotel room when Veronica isn’t there. And then, something happens after that dinner that explains how the plantation world and the modern world are connected.

Monáe does an adequate job in the role that she’s been given. And the movie’s cinematography, production design and costume design are actually very good. The actors who play the racists predictably portray them as caricatures of evil. The insidiousness of a lot of racists is that they hide their hate with fake smiles and polite mannerisms to the people they hate, but there’s no such subtlety in this story, since all of the villains are revealed early on in the story.

The biggest problem with “Antebellum” is the screenplay. The ending of the movie is absolutely ludicrous and it actually makes the African Americans in the story look dumb for not taking certain actions that could have been taken earlier. Therefore, “Antebellum” isn’t as uplifting to African Americans as it likes to think it is.

The tone of the movie is also uneven, because the slavery scenes are absolutely dark and brutal. But then the scenes with Sidibe and her sitcom-ish character are very out of place and dilute the intended horror of the movie. Sidibe is very good in the role, but the Dawn character was written as too comedic for this type of movie. And huge stretches of “Antebellum” are just plain boring, with no real suspense.

However, the main ridiculousness of “Antebellum” goes back to that plantation and the secret that’s revealed at the end of the movie. If people want to see the horrors of slavery depicted in an Oscar-worthy narrative film, then watch “12 Years a Slave.” Don’t watch “Antebellum,” which uses slavery as an exploitative gimmick as the basis for this moronic and not-very-scary horror movie.

Lionsgate released “Antebellum” on VOD on September 18, 2020.