August 8, 2020

by Carla Hay

“Creem: America’s Only Rock’n’Roll Magazine”

Directed by Scott Crawford

Culture Representation: The documentary “Creem: America’s Only Rock’n’Roll Magazine” features an almost entirely white group of entertainers and journalists (with one Asian and one African American) discussing the history of Creem, a Michigan-based rock magazine that was published monthly in print format from 1969 to 1989.

Culture Clash: Creem, which was considered the “edgier” alternative to Rolling Stone magazine, prided itself on being disrespectful of many artists; there were serious internal conflicts among Creem staffers; and Creem often had a lot of content that would be considered politically incorrect today.

Culture Audience: “Creem: America’s Only Rock’n’Roll Magazine” will appeal mostly to people who are interested in rock music or the magazine industry from the 1970s and 1980s.

The documentary “Creem: America’s Only Rock’n’Roll Magazine” gets its subtitle from the slogan of Creem magazine, which had a raucous ride in monthly print circulation from 1969 to 1989. The movie includes interviews with numerous people who either worked for the magazine and/or considered themselves to be regular readers of Creem. It’s a nostalgic look at a bygone era when print magazines had more clout than they do now, when it comes to influencing music artist’s careers and shaping pop culture.

The documentary (originally titled “Boy Howdy! The Story of Creem Magazine”) doesn’t gloss over the dark side of Creem’s history, but the overall tone of the movie is one that’s similar to how someone would look back on their rebellious youth. Almost everyone interviewed in the documentary was born before 1970.

One of the main reasons why the “Creem” documentary (directed by Scott Crawford) has an overall fondness for the magazine is because some of Creem’s former staffers were involved in making the movie and are interviewed in the documentary. Jaan Uhelszki, a former Creem senior editor, is one of the documentary’s producers, and she co-wrote the movie with Crawford. Connie Kramer, who used to be Creem’s associate publisher and was married to Creem co-founder Barry Kramer, is one of the documentary’s executive producers.

Another producer of the documentary is JJ Kramer, Barry and Connie Kramer’s son who inherited partial ownership of the magazine after Barry passed away in 1981. (Barry Kramer was not related to MC5 co-founder Wayne Kramer, who wrote this documentary’s original music score.) Susan Whitall, who was a Creem editor from 1978 to 1983, is an associate producer of the documentary.

It’s pretty obvious that the documentary was filmed over several years, because some of the artists look different now, compared to how they look in the documentary. However, their commentaries are insightful and offer the additional perspectives of people who were not only in the magazine but who also were fans of Creem. (Only a few of the artists interviewed in the documentary became famous after Creem’s publication ended in 1989.)

There’s an overabundance of people interviewed in the documentary, but the film editing is good enough where the soundbites aren’t too repetitive and each has something unique to say. The types of people interviewed for the documentary essentially fall into two categories: entertainers (usually music artists) and former Creem employees/other journalists.

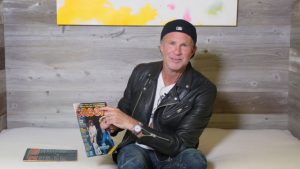

The music artists interviewed include Alice Cooper, Ted Nugent, Kiss singer/bassist Gene Simmons, Kiss singer/guitarist Paul Stanley, Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Chad Smith, Metallica guitarist Kirk Hammett, former R.E.M. singer Michael Stipe, Pearl Jam bassist Jeff Ament, the Black Keys drummer Patrick Carney, music producer Don Was, Suzi Quatro, Destroy All Monsters singer Niagra Detroit, former J. Geils Band singer Peter Wolf, Lenny Kaye, Mitch Ryder, Lamar Sorrento, Johnny “Bee” Bandanjek, Patti Quatro Ericson, Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore, Blondie guitarist Chris Stein, Joan Jett, Michael Des Barres, Scott Richardson, Keith Morris (founding member of the bands Black Flag and the Circle Jerks), and Redd Kross co-founding brothers Jeff and Steve McDonald.

In addition to Uhelszki, Connie Kramer and Whitall, the former Creem staffers interviewed in the documentary include Dave Marsh, who was Creem’s editor-in-chief from 1969 to 1973; Dave DiMartino, who was an editor from 1978 to 1986; Wayne Robins and Robert Duncan, who were editor-in-chief and managing editor, respectively, from 1975 to 1976; Ed Ward, who was West Coast editor from 1971 to 1977; Bill Holdship, who was a senior editor from 1980 to 1986; and Billy Altman, a reviews editor who worked for Creem from 1975 to 1985.

Creem alumni who were also interviewed include former staff writer Roberta “Robbie” Cruger, former editorial assistant Resa Jarrett, former staff photographer Michael N. Marks, former circulation manager Jack Kronk, former contributing writer Craig Karpel, former assistant to the publisher Sandra Stretke and former manager Toby Mamis. Other assorted journalists offering their comments in the documentary are Ann Powers, Legs McNeil, Scott Sterling, Ben Fong-Torres, Greil Marcus, John Holstrom, Josh Bassett, radio personality Dan Carlisle (who worked for Detroit’s WABX-FM during Creem’s early years) and photographers Bob Gruen and Neal Preston.

And there are some people from the worlds of art, movies or fashion who are included in the documentary, including artist Shepard Fairey, actor Jeff Daniels, former model Bebe Buell, fashion mogul John Varvatos and filmmaker Cameron Crowe, who started his writing career as a teenage music journalist in the 1970s for magazines such as Creem and Rolling Stone. Crowe’s real-life experiences as a beginner teenage journalist in the early 1970s became the inspiration for his Oscar-winning 2000 comedy/drama movie “Almost Famous,” which includes Philip Seymour Hoffman portraying Lester Bangs, Creem’s most influential writer.

Creem’s roots began in Detroit in 1969, when Barry Kramer (who owned shops in the area that sold music and drug paraphernalia) joined forces with a Brit named Tony Reay to co-found Creem magazine, with Kramer as publisher and Reay as editor. Rolling Stone magazine, which launched in 1967, was named after the Rolling Stones, the favorite band of Rolling Stone magazine co-founder Jann Wenner. In a cheeky nod to that idea, Creem was named after Reay’s favorite band Cream, the British blues-rock trio led by Eric Clapton.

Robert Crumb, also known as underground cartoonist R. Crumb, was recruited to come up with Creem’s original artwork, which included the magazine’s famous Boy Howdy mascot resembling a bottle of milk cream. It’s mentioned in the documentary that Creem offered to pay Crumb’s medical bills in exchange for his art services. Crumb’s illustrations and Creem’s irreverent humor often resulted in people describing Creem as the Mad magazine of rock’n’roll.

Reay’s stint as Creem’s founding editor didn’t last long, because he and Barry Kramer didn’t see eye-to-eye in the direction of the magazine. According to former staffers interviewed in the documentary, Reay wanted Creem to be a niche publication for blues-rock enthusiasts, while Barry Kramer wanted Creem to be a slick magazine that reached a wider rock audience. Reay parted ways with Creem, which hired Marsh as the next editor-in-chief in 1969, when Marsh was just 19 years old and had no previous experience editing a magazine. Marsh certainly didn’t take the job for the money, since he says that his Creem salary at the time was only $5 a week.

Marsh comments in the documentary “I had a vision for what the magazine could do for kids who were out there being ridiculed and beat up … The idea I had about Creem was that even in rock’n’roll, it had come to pass that there were stuffy ways of dealing with people. And I thought part of your job as a human being was to oppose that.”

Several artists interviewed about Creem in the documentary make comments essentially saying that Creem’s primary appeal was that it was a magazine made by and for rebels and misfits. Creem and Rolling Stone both considered themselves to be counterculture magazines when they first launched. However, Rolling Stone (which was originally based in San Francisco before moving its headquarters New York City in 1977) had aspirations that were more highbrow and more glamorous than Creem had.

It’s noted in the documentary that Rolling Stone co-founder Wenner (the magazine’s longtime editor-in-chief/publisher) loved hanging out with rock stars and other celebrities, which had an effect on the type of coverage that Rolling Stone gave to certain artists who were considered Wenner’s friends. Creem was the type of magazine that identified more with the fans who paid for albums and concert tickets. Bangs famously advised other music journalists to never make friends with rock stars in order to keep journalistic integrity, but it’s mentioned in the documentary that Bangs sometimes broke that rule himself.

Bangs, who was a freelancer for most of his career as a music writer/editor, is described by many in the documentary as a brilliant but fickle writer who was addicted to meth. Marcus says that when Bangs started writing for Creem in 1970, Bangs “turned [Creem] into a playground [with] … a wonderful sense of mocking everything.”

Crowe comments on the frequent conflicts between Bangs and Marsh: “Lester Bangs and Dave Marsh were like the two people that, within their collaboration, what they got to argue about is why and how to love the thing they loved. And what came out of that was desperate, reckless, raw, unforgettable coverage of this thing they were both in love with.”

Several people in the documentary comment that Creem’s “outsider” attitude had a lot to do with the fact that the magazine was based in the Midwest state of Michigan for most of its existence, instead of a big city on the East Coast or West Coast. The documentary gives a great overview of the Detroit music scene in the turbulent late 1960s and early 1970s, to provide necessary context of why Creem’s Detroit origins were crucial to the magazine’s original tone and outlook. Creem embraced subgenres of rock that Rolling Stone tended to dislike in the 1970s, such as punk and heavy metal.

Although Creem was known for championing a lot of artists who were ignored or bashed by other rock magazines, Creem was notorious for its vicious insults directed at artists and other celebrities. Sexist, homophobic, anti-Semitic and body-shaming comments were not unusual in Creem. And the magazine probably would’ve had a lot of racist comments too if not for the fact that white artists got almost all of the coverage in this rock-oriented magazine. Creem was also known for having female artists and models pose in sexually provocative pinup photos, while nude (but not pornographic) photos of women and men were not unusual in Creem.

Uhelszki admits that much of Creem’s content would be considered problematic or offensive enough that people could get fired it for today. “Everybody was politically incorrect,” she says of Creem’s staff at the time. Uhelszki remembers that back in Creem’s 1970s heyday, the inflammatory comments in the magazine were all part of Creem’s rebellious image.

Uhelszki also says that it wasn’t just the men on the male-dominated staff who wrote the misogynistic comments, because she wrote a lot of sexist content for the magazine too. “It was a boys’ magazine. It was meant for teenage boys,” Uhelszki comments in the documentary. “Did girls read it? Sure, they did. It was only sexually provocative when it was funny.”

While Creem was stirring up enough controversy where it was considered an inappropriate magazine for very young children, several former Creem staffers say in the documentary that there was chaos behind the scenes too, as Creem employees partied like the rock stars they gave coverage to in the magazine. In other words, drug-fueled behavior was part of the craziness. Creem’s original headquarters on Cass Avenue in Detroit was also in a run-down building in a crime-infested area, where it was not unusual for the female employees to be sexually groped on the streets on the way to and from the office.

People would also use the office as a “crash pad” to sleep and bring their personal lives to work with them, since the office would often be a battleground for arguments between employees and their significant others who didn’t work for Creem. And several of the employees mention that the staff had a love-hate relationship with Barry Kramer. Whitall comments, “Barry was an explosive editor … but he also had a sense of fun.”

The increasingly unsafe urban environment of Detroit became too much for the head honchos at Creem, so they decided to move to a completely different work environment. Creem’s headquarters relocated to a rural farm commune in Walled Lake, Michigan, where the magazine was based from 1971 to 1973. Creem’s crucial staff members lived and worked on the commune.

At the commune, the lines between personal and professional lives continued to blur for some staffers. In addition to Dave and Connie Kramer being a couple, some of the staffers were inevitably involved in co-worker romances. Marsh and Cruger were a couple, while Uhelszki was dating Charlie Auringer, who was Creem’s art director at the time.

Connie Kramer says in the documentary: “The women in the house … were much more monogamous than any of the men.” Uhelszki says of Creem’s Walled Lake headquarters, “It was a horrible place to be. And we were there for two years.”

Creem then relocated again in 1973. This time, it was to the Michigan suburban city of Birmingham, where the magazine experienced what many people consider to be the peak years of Creem. Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Smith, who grew up in the nearby city of Bloomfield Hills, remembers that when he was a kid, he was so excited to find out that Creem’s head office was close to where he lived, that he rode his bike to the office, and one of the first people he saw come out of the building was Alice Cooper. Smith says he was naturally star-struck.

The documentary includes some archival 1970s film footage of Creem staffers at headquarters, as well as many great photos from past issues of Creem. There’s a short segment on Uhelszki’s article “I Dreamed I Was Onstage With Kiss in My Maidenform Bra,” from Creem’s August 1975 issue. The article documented Uhelszki’s experience of getting to put on stage makeup with Kiss and joining the band on stage for a concert. It’s the type of article Rolling Stone magazine would never do, since Rolling Stone despised Kiss at the time. Kiss members Simmons and Stanley remember how the band argued about which member of Kiss would be the one Uhelszki would portray when she got her stage makeup done for the article.

The Boy Howdy mascot was such a part of Creem’s identity that the magazine got rock stars and other celebrities to pose for photos with fictional Boy Howdy beer cans. (A Boy Howdy sticker would be placed over real beer cans to make it look like Boy Howdy beer was real.) Not everyone was a fan of these promotional stunt photos. Longtime rock photographer Preston comments on the Boy Howdy beer cans: “The whole Boy Howdy thing was completely cheeseball, and I was mortified anytime I had to ask anybody to shoot with them.”

Another popular Creem photo feature was Star Cars, with each issue having a different celebrity posed with one of the celebrity’s vehicles. In 1977, Aerosmith lead guitarist Joe Perry notoriously posed for Creem with his mangled 1967 blue Corvette that he crashed in a car accident. Also included is a documentary segment on Creem’s Profiles, a one-page feature inspired by Dewar’s Profiles. Creem’s Profiles weren’t full-length interviews but were lists of artists’ likes, dislikes and other thoughts on various subjects.

The documentary also includes a segment about Creem’s famous section for reader mail, in which reader comments would be published next to sarcastic responses from Creem editors. Uhelszki says that the most famous reader letter they got was from Jett, the co-founder of the Runaways, who reacted to Creem’s extremely misogynistic review of the Runaways’ 1976 self-titled first album. In the review, Creem writer Rick Johnson said of the all-female Runaways: “These bitches suck … Girls are just sissies after all.”

In the documentary, Jett remembers her reaction to the review: “I was infuriated.” She says she was so angry that she showed up at Creem headquarters looking for Johnson, but he wasn’t there. “I bet he ran out the back door,” Jett quips in the documentary, which includes her voiceover reading of her letter that was published in Creem. The letter, which is directed at critic Johnson, says in part: “Since you seem to know that girls are sissies, come and see us sometime, and we’ll kick your fucking ass in.”

Just like what happens to a turbulent but successful rock band, the more popular Creem became, the more there was turmoil behind the scenes. The documentary details the main feuds that would eventually tear apart Creem’s original “dream team” senior-level staff. There was Barry Kramer vs. Marsh, who disagreed over editorial coverage and had fist fights over it. There was Marsh vs. Bangs, who also had physical altercations with each other and clashed over the direction in which the magazine should go. And there was Barry Kramer vs. Connie Kramer, who says that their marriage was ruined by cocaine addiction.

According to Uhelszki, Bangs wanted Creem to have more of a satirical edge, while Marsh wanted Creem to have more serious political content. Both Marsh and Bangs would eventually leave Creem: Marsh in 1973, and Bangs in 1976. Marsh went on to write for Newsday, Rolling Stone and other publications, while Bangs continued his freelance career and died of a Darvon overdose in 1982, at the age of 33. Even though Bangs was a known hardcore drug addict, several people in the documentary remember how shocked they were to hear about his death, because he had recently completely a stint in rehab.

Connie went to rehab and left Barry, because she says that he did not want to stop doing cocaine. They divorced in 1980. Barry tragically committed suicide by nitrous oxide suffocation in 1981, at the age of 37. Connie still seems to be experiencing denial and shame over his death because she says in the documentary that Barry “didn’t commit suicide” but “he wanted to end his life.”

Connie Kramer eventually sold Creem to Arnold Levitt in 1986. The magazine relocated to Los Angeles in 1987 and then ceased its monthly publication in 1989. Because this documentary is meant to showcase Creem before it was sold to Levitt, there’s hardly anything in the movie about the last few years of Creem. The magazine, licensed to a group of investors, was revived as a New York City-based bimonthly publication from 1990 to 1993, but that revival ultimately failed. The movie doesn’t include the legal disputes during the 2000s and 2010s over the Creem name and archives.

“Creem: America’s Only Rock’n’Roll Magazine” gives the impression that its candid look at the good, bad and ugly aspects of this magazine’s history is precisely because the magazine is no longer in business and former employees can speak more freely about people who are no longer their co-workers. It’s a much grittier and more honest portrayal of the wild and wooly days of 20th century rock journalism than, for example, HBO’s “Rolling Stone: Stories From the Edge,” a glossy 2017 documentary celebrating Rolling Stone’s 50th anniversary. Although the artists in the “Creem” documentary have important perspectives, the magazine’s former staffers are the ones whose behind-the-scenes stories resonate the most.

Greenwich Entertainment released “Creem: America’s Only Rock’n’Roll Magazine” in select U.S. cinemas on August 7, 2020.