June 24, 2020

by Carla Hay

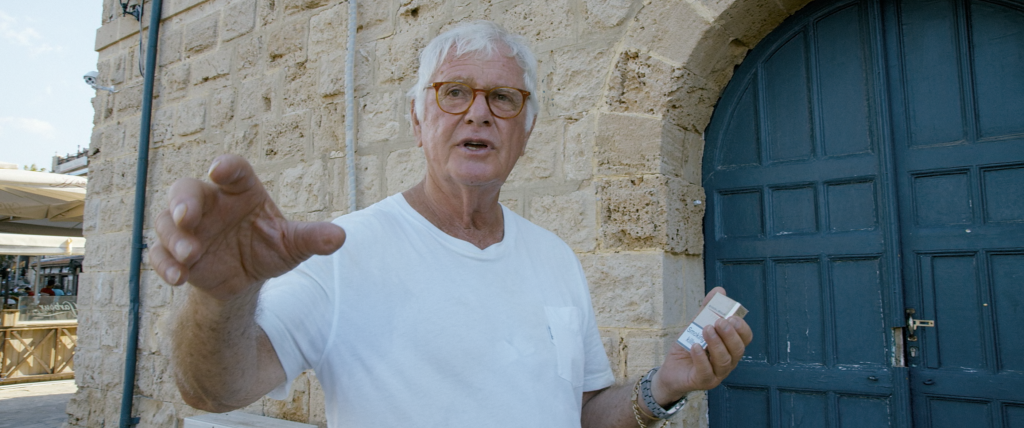

Directed by Peter Medak

Culture Representation: Taking place in England and Cyprus, the documentary “The Ghost of Peter Sellers” features director Peter Medak and an all-white group of other senior citizens talking about his disastrous 1973 experience making the comedy film “Ghost in the Noonday Sun,” starring Peter Sellers.

Culture Clash: Several people in the documentary say that Sellers was a nightmare to work with and that he deliberately sabotaged production of the movie.

Culture Audience: Aside from obviously appealing to Sellers fans, “The Ghost of Peter Sellers” will also appeal to people who are fans of 1970s European cinema and behind-the-scenes stories about difficult filmmaking experiences.

In 1973, director Peter Medak had such a traumatic experience making the comedy film “Ghost in the Noonday Sun,” starring British actor Peter Sellers, that he made a documentary four decades later to talk about what went wrong. That documentary is “The Ghost of Peter Sellers,” which is part therapy session, part quest for redemption and part cautionary tale about what can happen when a director of a movie loses control to a mentally unbalanced movie star. Sellers has been dead since 1980 (when he passed away at age 54), but it’s clear from watching this aptly titled documentary that the self-pitying Medak is still haunted by Sellers and won’t let go of the past.

Medak begins the documentary (which mixes new interviews with archival footage) by giving a brief background about himself and then describing how he got to direct “Ghost in the Noonday Sun.” When Medak met Sellers in 1972 at Alvaro restaurant (a celebrity hotspot) on King’s Road in London, Sellers was riding high as one of the biggest comedy stars in the world (he was best known for the “Pink Panther” movies), and Medak (who was born in Hungary in 1937) was a director whose career was on the rise, thanks to his breakout 1972 film “The Ruling Class.”

Sellers asked Medak if he wanted to direct a comedy film called “Ghost in the Noonday Sun,” which would star Sellers and co-star Spike Milligan, a frequent collaborator of Sellers. Milligan (who died in 2002, at the age of 83) was a well-known comedic actor/writer, whose credits included previous collaborations with Sellers, such as “The Goon Show,” “The Idiot Weekly, Price 2d,” “A Show Called Fred” and “Son of Fred.”

“For a director, it was irresistible,” Medak remembers of being offered this opportunity. But in hindsight, he says, “Like an idiot, I said yes.” What could possibly go wrong? Well, almost everything.

For starters, “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” was greenlighted for production based mostly on a concept rather than a well-written screenplay. Evan Jones and Milligan were credited with writing the screenplay, while co-writer Ernest Tidyman was uncredited. Jones’ previous film screenplay credits included 1963’s “The Damned” 1966’s “Funeral in Berlin” and 1971’s “Wake in Fright,” also known as “Outback.”

Here’s the gist of the very convoluted, messy plot of “Ghost in the Noonday Sun”: In the 17th century, on a pirate ship, an Irish cook named Dick Scratcher (played by Sellers) and three accomplices kill the pirate captain Ras Mohammed (played Peter Boyle), and Scratcher takes over the ship as the new captain. Scratcher and his crew then go on a quest to find the treasure that was buried by the murdered captain, using a treasure map as their guide. A series of misadventures ensue for the treasure hunters, including landing in the wrong country; kidnapping a boy who can see ghosts; threats of mutiny; and encountering Scratcher’s old friend Billy Bombay (played by Milligan).

What the filmmakers did not plan for and severely underestimated was how difficult it would be to make a movie that takes place on an unsteady boat. The film production in Cyprus was plagued by bad weather and a boat that kept breaking down, including an incident when a drunk navigator crashed the boat. And worst of all, according to people interviewed in the documentary: a star of the movie who went out of his way to ruin the film because he didn’t want to do the movie anymore.

In “The Ghost of Peter Sellers,” Medak revisits a lot of the people and retraces a lot of the steps to places in England and Cyprus that were part of the torturous process of making “Ghost in the Noonday Sun.” Medak is accompanied to many locations by his screenwriter friend Simon Van Der Borgh, who seems to have no real purpose in the documentary, other than as emotional support for Medak.

In London, Medak shows Van Der Borgh the location where Alvaro used to be. They also visit Norma Farnes, who was Milligan’s agent. Medak and Farnes hadn’t seen each other in about 42 years, but their reunion looks a little rehearsed and staged. (In fact, the beginning of the movie shows Medak asking someone to reshoot a scene where they’re supposed to greet each other.)

And there are also meetings/interviews with some members of the cast and production team of “Ghost in the Noonday Sun,” including producer John Heyman, who helped finance the movie but was not given producer’s credit; Film Finances managing director David Korda; actors Murray Melvin, Costas Demetriou and Joe Dunn (who was Sellers’ stunt double); boat recovery operations worker Costas Evagoru; and costume designer Ruth Meyers. (Heyman died in 2017, which gives you an idea how long ago some of these interviews must have been filmed.)

Also interviewed are several people who knew Sellers well, including personal assistant Susan Wood; his daughter Victoria Sellers; his American agent Maggie Abbott; and his London agent (from 1964 to 1968) Sandy Lieberson. Victoria Sellers was only 8 years old when “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” was made, but she seems to be in this documentary only so Medak can have an additional person in a long list of people talking about how Peter Sellers was a difficult and deeply unhappy person.

Medak even includes an interview with Rita Franciosa, widow of actor Tony Franciosa, who co-starred in “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” as Pierre Rodriquez, the only gentlemanly pirate on the ship. She says that Tony took the movie more seriously than Peter Sellers did. There’s no mention of Rita actually being on the film set, so her observations are second-hand at best. It’s just another example of Medak trying to gather a chorus of people in the documentary to validate the narrative that Peter Sellers was horrible, unprofessional, and largely to blame for the movie being a nightmare.

Medak also has a three-way commiserating session with director Piers Haggard (“The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu”) and director Joe McGrath (“The Goon Show”), where they talk about how working with Peter Sellers was an unpleasant experience for them. Robert Wagner, who co-starred with Sellers in 1963’s “The Pink Panther,” also says in the documentary that Sellers was a terrible co-worker.

In a separate interview, John Goldstone of Monty Python Productions weighs in with his opinion (even though Peter Sellers wasn’t affiliated with Monty Python) by saying that the way Medak was treated by Peter Sellers was awful and not how a comedy film set is supposed to be. This echo chamber of Peter Sellers bashing is Medak’s way of saying, “See, I’m not the only one who feels this way.”

Besides having extreme mood swings, being very fickle, and demonstrating a huge ego, Peter Sellers is described as someone who went out of his way to make life miserable for the cast, crew and other people on the team of “Ghost in the Noonday Sun.” Things got off to a bad start because the first day of filming in Cyprus was shortly after Sellers had ended his tempestuous engagement to Liza Minnelli. “He was catatonically depressed,” Medak remembers.

Some of the people in the documentary speculate that Peter Sellers probably had an undiagnosed mental illness. He would go through extreme emotional “ups” and “downs.” And he would change his mind on a whim, by being in love with an idea one minute and then hating it the next minute. Regardless of what was going on in his personal life or mental health, Sellers made it clear to everyone after filming started that he didn’t want to do the movie.

According to Medak, Peter Sellers resorted to various tricks, such as not showing up for work for several days, by claiming he had a serious medical problem requiring him to be bedridden, and he had a doctor’s letter to “prove” it. But Medak remembers finding out that the illness was a lie when he saw a newspaper article with a photo of Peter Sellers gallivanting around London with Princess Margaret on a day that Sellers claimed to be sick in bed at home. In the documentary, Medak interviews Dr. Tony Greenburgh (Sellers’ personal doctor), who admits that writing a fabricated letter is something he probably would have done for Sellers at the time. “He was a good friend,” says Greenburgh.

Peter Sellers also began acting as if he, not the director or producers, were running the show, according to Medak. He demanded that producer Thomas Clyde be fired. (Clyde got to keep his producer’s credit, along with producer Gareth Wigan.) Robin Dalton, who was Medak’s agent from 1968 to 1975, says in the documentary: “It’s the only time I ever remember where the producers got sacked after the first week [of filming] by the star.”

Medak remembers one day on the film set that Peter Sellers began barking orders at people and declaring that he was now in charge. Medak says that the way Peter Sellers was acting was very much like the domineering Fred Kite character that he played in the 1959 comedy film “I’m Alright Jack.” Needless to say, Medak and Sellers clashed on the film set.

But Peter Sellers also had problems with co-star Milligan. Medak says that Sellers and Milligan had an intense rivalry with each other, with each one trying to outdo the other to prove who was funnier. Things got so bad between Sellers and Milligan that Sellers demanded that he not share any scenes with Milligan. Certain scenes had to be rewritten and reshot because of these demands.

And why didn’t Medak quit? He says in the documentary that he couldn’t afford to quit because his wife was expecting their second son, and the family needed the money at the time. If Medak had quit, not only would he have to give up his director’s fee, but there would also be a possibility that he would be sued for breach of contract.

But it wasn’t just about the money. Medak admits that he was also thinking about his reputation, and he felt that he had something to prove by finishing this disaster of a movie. Peter Sellers was so desperate to get out of filming “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” that he offered Medak half of his actor’s fee if Medak quit the film. Sellers hoped that Medak quitting would shut down the film for good. Medak refused to quit, which no doubt fueled even more of Sellers’ resentment toward Medak.

In the middle of all this turmoil about the movie, there was a bizarre interlude when Peter Sellers filmed a series of cigarette commercials directed by Medak. Antony Rufus Isaacs, a producer of the commercials, is one of the people briefly interviewed in the documentary. After they filmed the commercials, they went right back to the torment of getting “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” completed.

Medak’s quest in reliving this trauma comes across as earnest but a little pathetic. He has a large scrapbook for “Ghost in the Noonday Sun,” which he carries around in the documentary like someone who had a love/hate relationship with high school would carry around their high-school yearbook. And more than once, some people in the documentary (such as Heyman and Farnes) essentially tell Medak: “Get over it.”

Multiple times in the movie, Medak breaks down and cries when he talks about how the experience of making “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” scarred him for life. But it’s hard to feel complete sympathy for him when he later admits that he walked off the job on several other movies that he was hired to direct after “Ghost in the Noonday Sun.” Medak blames this unprofessional behavior on the bad experience that he had with Sellers.

In the beginning of the documentary, Medak makes it sound like Sellers and “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” ruined his career. In reality, which he admits toward the end of the film, Medak had a long career in directing movies and TV shows after that negative experience. There’s even a photo sequence during the documentary’s end credits showing Medak on the sets of many of these subsequent projects.

And this is where Medak’s privileged blind spot is on display. Despite having his own history of being difficult and unprofessional on jobs that had nothing to do with Peter Sellers, Medak still continued to get opportunities to direct movies and TV shows for decades. If a director who’s a woman or a person of color ever behaved in the same way, they wouldn’t be given as many opportunities as Medak was given.

Therefore, all of Medak’s whining about Peter Sellers in the documentary makes Medak look like a schmuck. Peter Sellers was never a longtime collaborator of Medak’s. They did just one movie together, so Medak’s career wasn’t as intertwined with Sellers as he would like viewers of this documentary to think it was.

Heyman put it best in the documentary when he comments on making “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” and how it really affected people’s careers: “I don’t know how many nails there are in a coffin, but this [“Ghost in the Noonday Sun”] is a very small nail. We’re all to blame.” In other words: Yes, the movie was a disastrous flop, and other people besides Medak were affected too, but it didn’t ruin anybody’s career.

Therefore, Medak really can’t blame any subsequent career decline on Peter Sellers, whom Medak seems obsessed with on an unhealthy level. During one of Medak’s crying bouts in the film, he admits that one of the reasons why he feels so hurt is because he was and still is a huge fan of Sellers, whom Medak calls a “genius.” Yes, but you only worked with Sellers on one movie all the way back in 1973. Move on.

And this is the other problem with the documentary not being entirely truthful and very slanted to make Medak look like a “victim.” At the end of the documentary, it’s mentioned that Columbia Pictures thought “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” was such a mess that the studio shelved the film. While it’s true that “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” was never released in cinemas, it was eventually released in 1985 on home video.

This home-video release is never mentioned in the documentary, because the documentary misleads viewers into thinking that “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” is locked away somewhere, never to be seen by the public. Because the documentary omits that “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” was released (just not in cinemas, as Medak had hoped) and is available to be seen by the public, it’s just another example of how Medak has a “poor me” attitude that is unrelenting and ultimately very annoying.

In the beginning of the documentary, Medak gripes about “Ghost in the Noonday Sun,” by saying, “For 43 years, I covered up this very dark spot on my life. I carried this grudge against myself … for all these years.” Now that Medak has directed this documentary and aired out his grievances about Peter Sellers, perhaps he can find better use of his time, by appreciating the good things in his life instead of blaming his career problems and self-identity on a dead one-time co-worker and a little-seen bad movie he made decades ago.

1091 Pictures released “The Ghost of Peter Sellers” on digital and VOD on June 23, 2020.