October 22, 2022

by Carla Hay

“Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power”

Directed by Nina Menkes

Culture Representation: In the documentary film “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power,” American filmmaker Nina Menkes and a group of filmmakers and film/culture experts (predominantly white, with some African American, Asians and Latinas) discuss how the male-dominated film industry affects the way that women are depicted on-screen in movies.

Culture Clash: The documentary shows examples of how the “male gaze” of male directors and other male filmmakers often portray women as sex objects instead of fully formed human beings.

Culture Audience: “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in filmmaking and seeing how misogyny and sexism against women are ingrained in many movies.

“Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” will undoubtedly make some viewers uncomfortable in how it clearly demonstrates why misogyny and the objectification of women in movies are so pervasive. This documentary should be required viewing for anyone who cares about how manipulated images in movies can play a role in enabling sexism against women in society. Although some people might be in denial about it, the fact is that movies have a great deal of influence in how people behave, how they want to be perceived, and how they treat other people in real life.

Directed by Nina Menkes, a filmmaker who often makes speaking appearances about sexism in cinema, “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” has interviews with several film experts, but the movie is also partially formatted like a university lecture, which might be somewhat of a turnoff to some viewers of this documentary. The movie’s lecture scenes (from Menkes’ presentation “Sex and Power, the Visual Language of Cinema”) were filmed at Walt Disney Modular Theater at the California Institute of the Arts. Menkes speaks on stage and shows several movie clips on a video projection screen as examples of how the “male gaze” in filmmaking has resulted in sometimes subtle, sometimes obvious ways of how women are exploited and objectified on screen.

And the images of women often are far from empowering: Women on camera in movies are all too often being portrayed as subservient to men or existing mainly to please men. With some exceptions, when men and women co-star in a movie together and get equal billing, the men usually get more dialogue and screen time than the women. And in non-pornographic movies, women are expected to get fully naked on camera a lot more than men are expected to get fully naked. Menkes and the documentary do not put the blame only on male filmmakers for perpetuating this type of sexism in cinema, because it’s pointed out that some female filmmakers are just as guilty of the same sexism against women.

The fact remains though that men are the majority of directors, cinematographers and editors: the three types of filmmaking jobs that have the most influence in how performers look on screen. And that’s why the term “male gaze” came into existence. Early on in “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power,” the phrase “male gaze” is defined for viewers who don’t know what it means in cinematic terms. Film theorist Laura Mulvey, who is interviewed in the documentary, is credited with being the first to coin the term “male gaze” in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

The “male gaze” is considered to be a cinematic angle or viewpoint where women are presented as mainly existing to be pleasurable, passive or inferior to men. This is not the same thing as appreciating a woman’s inner or outer beauty. The “male gaze” point of view specifically shows in subtle and obvious ways that the men in the movie have the most control and power, while the women in the movie are never the men’s equals.

Mulvey says in the documentary that when she was in college, she watched a lot of movies. And it dawned on her: “Part of my pleasure in all of this filmgoing was that I was watching these movies [like] a male spectator.” She saw that the women on screen were often presented to be looked at, but not really seen as equal to the men. That feeling of “to be looked at-ness” (a phrase that Mulvey also coined) was also part of Mulvey’s awakening to the practice of female objectification in movies.

California State University at Long Beach faculty member Rhiannon Aarons comments, “Even though Mulvey’s foundational work was written in the ’70s, we still totally normalize the male gaze in cinema. I think the majority of people don’t ever question that form of looking. It’s so normal. It’s like asking if a fish is wet.” Filmmaker/TV producer Joey Soloway (who identifies as non-binary) comments on “male gaze” sexism: “To name it, to show it, is something that I think can change the world.”

Award-winning filmmaker Eliza Hittman (whose directorial credits include 2017’s “Beach Rats” and 2020’s “Never Rarely Sometimes Always”) offers this perspective: “It’s not just optical. It’s perceptual.” She cites actor/director Robert Montgomery’s 1947 film “Lady in the Lake” (which has a main character showing misogynistic distrust of women) as “an extreme example of what subjectivity is. It aligns with my ideas about a male point of view and a male gaze.”

Several clips from movies are used as examples of scenes that objectify females in a sexual way. The movies include 1947’s “The Lady from Shanghai ” (directed by Orson Welles); 1981’s “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (directed by Bob Rafelson); 1989’s “Do the Right Thing” (directed by Spike Lee); 1998’s “Buffalo 66” (directed by Vincent Gallo); 2003’s “Lost in Translation” (directed by Sofia Coppola); 2017’s “Blade Runner 2049” (directed by Denis Villeneuve); 2019’s “Bombshell” (directed by Jay Roach); 2020’s “Cuties” (directed by Maïmouna Doucouré); and 2020’s “365 Days” (directed by Barbara Bialowas and Tomasz Mandes). Although the documentary focuses primarily on how women are objectified in cinema, “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” includes a brief example of a man being sexually exploited on camera, by showing the scene in 1975’s “Mandingo” (directed by Richard Fleischer) where a white woman forces an enslaved African American man to have sex with her.

UCLA Film & Television Archive director May Hong HaDuong acknowledges: “I think sometimes, with films that are part of the canon, that are part of the ‘best’ films, there is a reticence to even question how they were made and the stories they tell. And I think it’s okay to to still love and see a film, and say it was great, but that it has some issues. And I think without questioning it, we’re doing a disservice to our own humanity.”

“Daughters of the Dust” director Julie Dash says, “As filmmakers, we have to be courageous and willing to be that force, and be willing to speak our minds, and say, ‘Hey, wait a minute. What’s wrong with this picture? What’s the visual rhetoric we’re looking at? It doesn’t feel good. It doesn’t feel correct. Let’s rethink this.'”

In the documentary, Menkes presents a theory that there’s a direct line between visual language of cinema, employment discrimination (against women in the film industry) and sexual abuse/assault. The employment discrimination is obvious when you consider how actresses over the age of 60 are rarely hired to be in movies as sexy, leading characters with an active love life. By contrast, male actors over the age of 60 can be cast as sexy leading characters with an active love life, and they usually have a female love interest in the movie who’s at least 15 to 20 years younger. The gender discrimination is even more prevalent when it comes to who gets cast as the headlining stars of action movies.

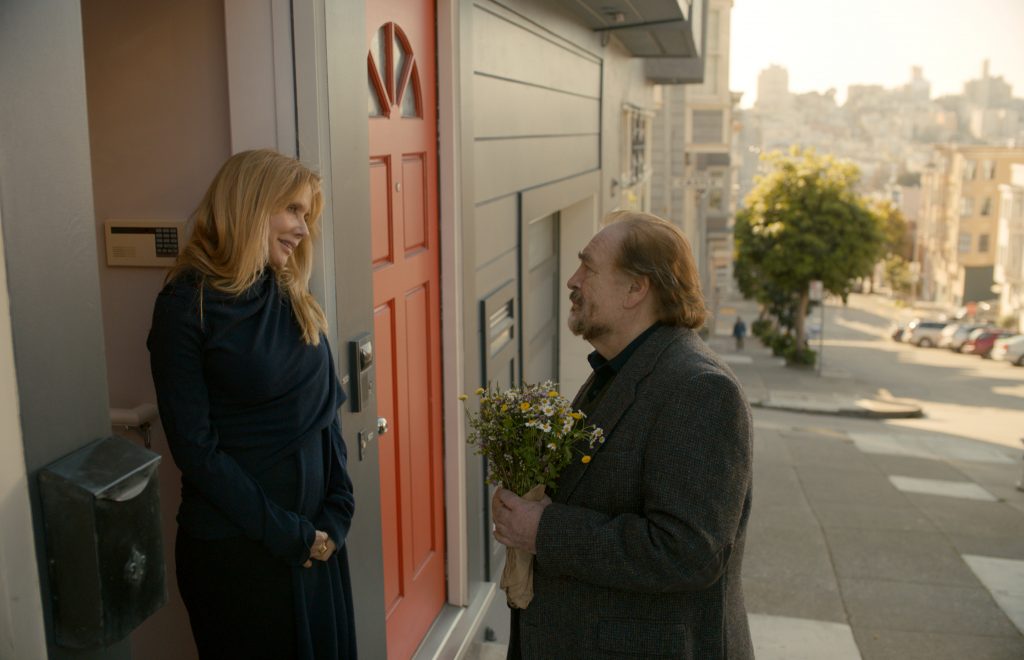

Rosanna Arquette, an actress who was 18 when her first movie (the 1977 TV-movie “Having Babies II”) was released, says that now she’s a middle-aged woman, she’s lost out on many jobs for what she thinks is age discrimination: “I got a great movie lately. It would’ve moved the needle. And they decided to go younger [casting a younger actress for the role] … That happens a lot. I have a lot of sadness even talking about it, because I love to work.”

The “male gaze” means that women in front of the camera are held to higher standards, in terms of pressure to look youthful and be of a certain body type, usually slender. Aarons says, “I think this visual language really contributes to female self-hatred and insecurity in a way that is not insignificant. What is normalized as beauty is seen specifically and dominantly through a male gaze.”

It’s hard to argue with this fact: Male actors can be considered “sex symbols” when they have gray hair and wrinkles, while actresses with gray hair and wrinkles are rarely considered “sex symbols.” Catherine Hardwicke (whose directorial credits include 2003’s “Thirteen” and 2008’s “Twilight”) comments, “I don’t worry if a guy has wrinkles because it just makes him look rugged as they get older, but you don’t want to think that for women.”

Who gets to decide what’s sexy? Who gets to influence people into thinking what’s sexy? In many cases, these influencers are the filmmakers who portray these actors and actresses as sex symbols, according to what the (usually male) filmmakers want. That type of influence has far-reaching effects on how people around the world perceive themselves. It’s probably no coincidence that women are the majority of people who get anti-aging plastic surgery.

Menkes sees five ways that the “male gaze” and sexism affect choices during the shot design, which is how a scene is filmed: (1) subject/object; (2) framing; (3) camera movement; (4) lighting; and (5) narrative positions of the characters, which are influenced by the previous four factors. For example, there are too many movies to name where the camera takes an ogling view of a woman: Her body is looked at up and down, sometimes in slow motion, while the men in the same movie don’t get the same camera treatment. Sometimes in these body-ogling scenes, the women’s face is not seen, as if her face doesn’t matter because she’s just an anonymous sex object to be stared at in a leering way.

Similarly, women are more likely than men to have their body parts singled out on camera for close-ups or camera angles that are meant to be sexually arousing. (We all know which body parts they are.) This type of filmmaking has become so common, many viewers don’t question it or don’t even think about it. “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” shows in no uncertain terms that this type of complacency is part of the sexism problem and why sexism continues to affect women and girls in a negative way.

Menkes and some other people who comment in the documentary come right out and say that “male gaze” sexism also plays a role in rape culture. Dartmouth College faculty member/filmmaker Iyabo Kwayana says, “I think we have to consider that it is through the formal visual language, we are effectively communicating meaning. It has to do with how [camera] shots are composed and framed, how they’re assembled, and ordered in a sequence of shots … If the camera is predatory, then the culture is predatory as well.”

The constant barrage of “male gaze”-directed images in movies that try to dictate what is “sexy” and “not sexy” in a woman can have real-world consequences on women’s self-esteem. As psychoanalyst Dr. Sachiko Taki-Reece says in the documentary about how a typical woman reacts to these movie images that are usually decided by men: “For women, because you are looking at those films, for instance, she would like to shape herself to be the object of the gaze. But she thinks, ‘Some part of me is not matching to that image.’ She feels empty. That’s the problem.”

Dr. Kathleen Tarr, who works with the Geena Davis Institute Task Force and Stanford University, comments on how sexist portrayals of women of movies can have consequences for women’s careers: “Absolutely, objectification of women impacts hiring practices … It becomes this way of dealing with women that is primarily around their sexual value. If they’re attractive to you, it absolutely has to do with how you’re treated on the job.”

An obvious and common question comes up in these types of discussions: “Why don’t more women just become movie directors?” The answer isn’t as simple as more women just need to go to film school, because there are sexist barriers to actually getting hired in the real world. The documentary cites a Los Angeles/San Diego State University study that found that about 50% of film school students in America are women, but women are less than 15% of the directors of the top-grossing movies in any given year.

Director/activist Maria Giese explains: “People are really happy for women to be attending film schools at parity with men, as long as they’re paying money into the system. But when we move into the professional playing field, and we’re asking the industry to pay [equal] money out to women, that’s where the door gets closed. Hollywood has been the worst violator of Title VII of any industry in the United States of America.”

Award-winning director Penelope Spheeris says when she was in school, including when she getting her master’s degree, “It never occurred to me to be a director.” That’s because in many people’s minds, the image of a movie director is that of being one specific demographic. As actress Charlyne Yi put its it: “Gender is a huge factor when you look around [movie] sets. Things haven’t changed that much. It’s mostly white men.”

“Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” (which had its world premiere at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival) certainly presents important visual evidence to bolster the premise of this documentary. However, the movie isn’t without some flaws. Perhaps the biggest flaw is in the last third of the film, which turns into Menkes going into a self-promotion tangent: She shows clips from her own movies as examples of a “female gaze” that empower women or have women on an equal level as men on camera. This part of the documentary just looks like ego posturing, Menkes patting herself on the back, and perhaps exaggerating the impact that her movies have had on the movie industry.

“Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” admirably gives some mention to female director pioneers, such as Alice Guy-Blaché and Dorothy Arzner. However, “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” should have given more credit to contemporary women filmmakers who are avoiding the “male gaze” sexism trap. The documentary would have been enriched if these female filmmakers gave analyses of certain scenes in their movies where they made choices to present women on camera in an empowering way. Instead, “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” kind of fizzles when the documentary veers off into what looks like Menkes doing an infomercial/sizzle reel of her own work. That’s not to say that Menkes shouldn’t have given analysis of her own work in this documentary but that she should’ve let more female filmmakers in the documentary have the chance to do the same.

The documentary also misses the mark by not including any perspectives of any male directors, particularly those who’ve used “male gaze” sexism, to get their side of the story of why they made these choices. (No men are interviewed in the documentary at all.) It’s very easy to dole out criticism of people in a documentary when those people don’t get a chance to respond in the documentary. It’s much harder to confront those people and give them a chance to explain their points of view in the documentary.

Other people interviewed in “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” include “Liberating Hollywood” author Maya Montañez Smukler, Global Media Center for Social Impact founder Sandra de Castro Buffington, cinematographer Nancy Schreiber, intimacy coordinator Ita O’Brien, artist/activist Laura Dale and culture transformation scholar Dr. Raja G. Bhattar. Dale shares a story that she says happened to her when she was an actress, she refused to do a sex scene that wasn’t in the script. She later got an ominous message from a female casting agent, who made this thinly veiled threat in an attempt to coerce Dale to do the sex scene: “We can fix this so won’t destroy your life.”

“Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” comes across as an echo chamber of interviewees who essentially agree with the arguments that Menkes has in her presentation. As valid as many of these issues are, this documentary cannot be considered truly well-balanced if it doesn’t present opposing points of view. It would have made for a higher-quality documentary if it included a healthy exchange of dialogue from people with conflicting opinions.

In “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power,” Menkes makes a statement that could be considered a response to any criticism she gets about these issues. In answer to anyone who thinks she’s just an uptight feminist, Menkes has this to say in the documentary: “If you are a heterosexual male, and you want to photograph some woman’s behind, I am certainly not the sex police. I’m not telling you, ‘Don’t do that.’ I’m just pointing out the fact that a whole lot of majorly acclaimed directors through time have done just that. There isn’t a whole lot of wiggle room for those of us seeing these things and are sick of the results of that kind of attack on our selfhood.”

Kino Lorber released “Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power” in select U.S. cinemas on October 21, 2022. The movie is set for release on digital and VOD on December 6, 2022.