July 7, 2023

by Carla Hay

Directed by Sam Pollard

Culture Representation: Covering the late 1880s to the 1950s in the United States, the documentary film “The League” features a predominantly African American group (with some white people) of baseball experts and cultural commentators discussing the Negro Leagues of American baseball, during an era when professional baseball was racially segregated in the United States.

Culture Clash: Despite the oppression of racism, the Negro Leagues helped African American communities economically and influenced how Major League Baseball was played, but racial integration caused the MLB to recruit the best Negro Leagues players, eventually leading to the Negro Leagues going out of business.

Culture Audience: “The League” will appeal primarily to people who are fans of American baseball and are interested in watching documentaries about African Americans in professional baseball.

“The League” has an impressive array of interviews and archival footage that give a comprehensive look at the Negro Leagues of American baseball. This highly informative documentary is at times a little too dryly academic, like a university lecture. However, it’s still essential viewing for anyone who cares about baseball, American history and the important role that the Negro Leagues had in both. “The League” had its world premiere at the 2023 Tribeca Festival.

Directed by Sam Pollard, “The League” follows a very traditional format of being a mixture of footage and interviews. Pollard made this statement in the movie’s press kit about how he assembled this documentary: “My vision was simple. Find voices of those who played the game, surround them with historians and fans of the Negro Leagues, use as much archival footage and stills I could find and, to add drama, shoot period recreations and create animation that would add another level of cinematic texture to the film.”

Pollard added in the statement, “Fortunately, I was able to find the voices of former Negro League players because Byron Motley (whose dad, Bob Motley, had been a Negro League Umpire) had interviewed and recorded many former players years ago. It was a treasure trove of wonderful voices and added immensely to the telling of the story. Also, fortunately many of the die-hard Negro League historians had access or knew where to find footage that I had never seen, which added enormously to visualizing the story.”

The Negro Leagues began out of necessity, because only white men were allowed to play in Major League Baseball (MLB), until Jackie Robinson famously broke through this racism barrier in 1947, by being the first African American to play for MLB. The Negro Leagues got off to a rocky start in 1887, when the National Colored Base Ball League (a minor league) lasted just two weeks. In 1920, the National Colored Base Ball League was formed, followed by several other leagues that had African Americans (and a small minority of Latinos) as the players.

Most of “The League” documentary covers the Negro Leagues era between the 1920s and 1950s. The Negro Leagues played their last season during Jim Crow racial segregation in 1951, and then faded away by the 1960s. The most successful of these leagues (and the fiercest rivals to each other) were the National Negro League, the Negro American League and the Eastern Colored League. Some other Negro Leagues that existed were the American Negro League, the East–West League and the Negro Southern League. The first Colored World Series took place in 1924, in a best-of-nine competition between the Negro National League champion Kansas City Monarchs and the Eastern Colored League champion Hilldale Club. The Monarchs won in a 5-4 final result.

The biggest strength of “The League” documentary is how it clearly shows the historical context of the ups and downs of the Negro Leagues were directly tied to racial segregation and racial integration laws. Adrian “Cap” Anson, a white first baseman whose MLB championship career peaked in the 1880s, is singled out in the documentary as being one of the driving forces in making MLB a “whites only” group. Anson would often refuse to play in a game if the other team had players who weren’t white.

Anson’s racist actions were validated by the Plessy vs. Ferguson case of 1896, when the U.S. Supreme Court decided to uphold federal protection of racial segregation laws, under the notion that racial segregation could be separate but equal. It led to the Jim Crow era in the United States, when it was legal to racially segregate people by having “whites only” places and services, and any other race would have to do whatever was dictated by what the white lawmakers decided. It was under this legal racial segregation that the Negro Leagues were born.

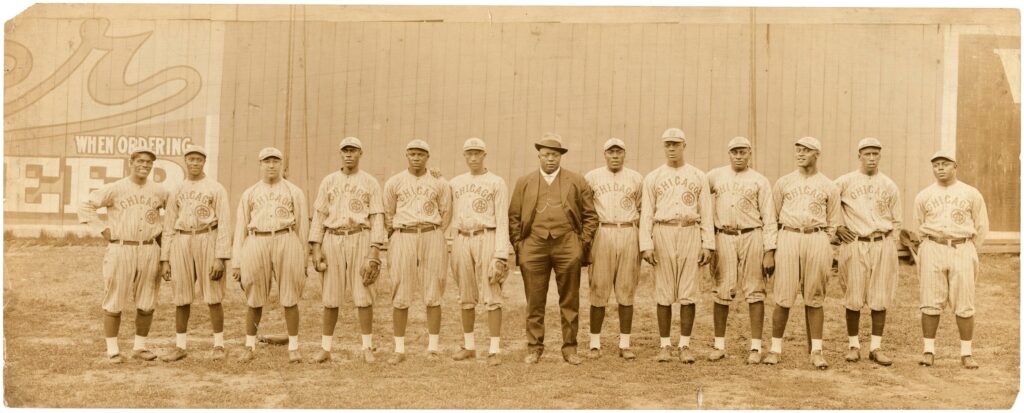

Another big part of American history that affected the Negro Leagues was the Great Migration, which refers to African Americans relocating from states in the U.S. South to go to other states in search of better economic opportunities and states that had little or no racial segregation laws. Chicago was one of the cities that saw an influx of many African Americans because of the Great Migration, which was encouraged by the African American-oriented newspaper the Chicago Defender. Perhaps it was no coincidence that the Chicago American Giants were considered one of the best Negro League teams, as mentioned by several people who are interviewed in the documentary.

“The League” does an excellent job of giving vivid depictions of some of the larger-than-life personalities who were major influencers in the Negro Leagues. Chief among them was Andrew “Rube” Foster, founder of the Negro National League and owner of the Chicago American Giants. (Junius “Red” Gaten, who was Foster’s assistant, is one of the people heard in the documentary’s archival interviews.) Foster used to be a baseball player himself, and he is credited with inventing the screwball pitch, also known as the fadeaway. Foster’s spectacular baseball career was curtailed by his mental health issues, and he was put in a psychiatric facility. Foster died in 1930, at the age of 51.

Kent State University history professor Leslie A. Heaphy, author of “The Negro Leagues, 1869-1960,” says that the Negro Leagues had a slump in the 1930s, partially due to Foster’s death and partially due to the Great Depression. In the years when the Negro Leagues thrived, African American communities that had Negro League games reaped the financial benefits, because these games created jobs in the communities. The Negro League games became so important for many spectators, they began to travel outside their home areas to attend these games. Pittsburgh became an important hub for these travels, says journalist Mark Whitaker.

In the documentary, journalist Mal Goode talks about the extremely competitive rivalry between the Pittsburgh Crawfords owner William “Gus” Greenlee and Homestead Grays owner Cumberland Posey, including regular “poaching” of each other’s star players, such as Josh Gibson. Edward “Ed” Bolden, who founded the Eastern Colored League and owned Hilldale Club, is frequently mentioned in the documentary as an important vanguard in the Negro Leagues. There were white people who owned some Negro Leagues teams, but the Negro Leagues were also important opportunities for black people to own professional baseball teams at a time when only white people were allowed to own MLB teams.

Another famous business personality for the Negro Leagues was Effa Manley, who is often called the First Lady of the Negro Leagues. Manley was not the first woman to own a Negro League team (Olivia Taylor was the first), but Manley was the most well-known female Negro League team owner because of her charismatic personality. Manley’s vague racial identity (a lot of people weren’t sure if she was white or a light-skinned black person) added to the mystique about her personal background.

“The League” could have used more exploration of what it was like to be a female baseball player in the Negro Leagues. There were a few, such as Marcenia “Toni” Stone (second base), Mamie “Peanut” Johnson (pitcher) and Constance “Connie” Morgan (second base). The issue of sexism in the Negro Leagues is mentioned mainly in reference to what Manley experienced, but “The League” documentary should have had better inclusion of other women who broke through gender barriers in the Negro Leagues.

The documentary mentions that many of today’s baseball techniques that combine athletic skills with entertainment flair can be traced back to the Negro Leagues. Back when the Negro Leagues existed, many white players looked down on the African American players who would have a flamboyant performance style to baseball playing. The word “showboating” at the time was code for baseball players who didn’t play “white enough.” It’s similar to how the Harlem Globetrotters changed the way many people played basketball.

The voices of Negro Leagues players who can be heard in the documentary’s archival interviews include Harold Tinker, Monte Irvin, Wilmer Harris, Buck O’Neil Jr., “Prince” Joe Henry, Bob Feller, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Max Manning, Larry Doby, Wilmer Harris and Judy Johnson. Many of these players also became managers of their respective teams. Also featured in archival interviews are writers Maya Angelou and Amiri Baraka; Paul Robeson Jr., whose famous actor father was a desegregation activist; Lloyd Brown, who was a community organizer and Paul Robeson Sr. biographer; and Odile Posey Stribling, sister-in-law of Homestead Grays player/manager/owner Cumberland Posey.

People who are interviewed on camera for “The League” include historian James Brunson III, journalist Andrea Williams, cultural critic Gerald Early, historian Lawrence D. Hogan, historian Donald Spivey, historian Rob Ruck, American National League scholar Larry Lester, journalist Shakeia Taylor, Negro League scholar Phil Dixon, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick, and Negro Leagues scholar Jim Overmyer. Also interviewed is Center for Negro League Baseball Research founder/executive director Layton Revel, who is also a researcher for the Negro Southern League Museum.

Breakthrough baseball player Robinson is the most famous alum of the Negro Leagues, since he was the first to cross over and become a player for MLB. Lester says of Robinson: “He was an ink spot on a white canvas of injustice.” Robinson has the most name recognition for Negro Leagues players, but several people in the documentary say that Satchel Paige was the best player from the Negro Leagues. Other famous Negro Leagues alumni, who also got inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, include Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Roy Campanella, Willard Brown, Cool Papa Bell and Buck Leonard.

It’s mentioned that Latino players, particularly from Cuba and other Caribbean nations, were integrated into the Negro Leagues because they weren’t allowed to become MLB players during the years when MLB was a “whites only” group. Some of the notable Latino players for the Negro Leagues included José Méndez, Martín Dihigo, Emilio “Millito” Navarro, Luis Márquez and Minnie Miñoso. Many of these Latino players identified as Afro-Latino.

“The League” is the type of documentary that benefits from having exclusive archival interviews and a well-chosen group of experts who give commentary. There is a scholarly and deliberately paced tone to the movie that might not appeal to people with very short attention spans. However, most people watching “The League” will learn something new about baseball, American history, and some of the extraordinary people involved in the Negro Leagues.

Magnolia Pictures released “The League” in select U.S. cinemas, exclusively in AMC Theatres, on July 7, 2023. The movie will be released on digital and VOD on July 14, 2023.