March 24, 2024

by Carla Hay

“Carol Doda Topless at the Condor”

Directed by Marlo McKenzie and Jonathan Parker

Culture Representation: The documentary film “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” features a predominantly white group of people (with a few African Americans and Asians) who are former associates or social commentators who discuss the life of Carol Doda, America’s first famous topless dancer.

Culture Clash: Doda’s nudity work caused controversy, got her arrested a few times, and sparked social change and debate over female nudity in a workplace setting.

Culture Audience: “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” will appeal primarily to people interested in documentaries about controversial people and social changes that happened in the United States in the 1960s.

“Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” is a fascinating but somewhat formulaic documentary that tells the story of Carol Doda, America’s first famous topless dancer. The movie looks at both sides of the debate over whether or not she was a feminist icon. “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” could have used better film editing and more research, since there are big gaps in her life that are missing or inadequately explained in the documentary. However, it’s an overall entertaining documentary to watch as a time-capsule aspect of the 1960s sexual revolution.

Directed by Marlo McKenzie and Jonathan Parker, “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” is based partially on the 2018 non-fiction book “Three Nights at the Condor: A Coal Miner’s Son, Carol Doda, and the Topless Revolution,” written by Benita Mattioli, wife of original Condor nightclub co-owner Pete Mattioli, who are both interviewed in the documentary. One of the documentary’s producers is Lars Ulrich, drummer for the San Francisco-based rock band Metallica, which got its start in San Francisco’s 1980s nightclub scene in the same area where Doda found fame two decades earlier.

“Carol Doda Topless at the Condor,” which had its world premiere at the 2023 Telluride Film Festival, is a typical mix of archival footage and interviews that were filmed exclusively for the documentary. It’s a celebrity biographical documentary that focuses almost entirely on the “fame” period of time in the celebrity’s life. Most of the people interviewed are those who used to work with her during the height of her fame in the 1960s.

The documentary has very little information about Doda before she became famous. It’s mentioned several times by people interviewed in the documentary that Doda was deliberately secretive about what her life was like before she became a dancer. However, if this documentary’s filmmakers attempted to find out more about Doda’s pre-fame life, none of that information ended up in the documentary.

Most of the documentary’s scant pre-fame information about Doda (who was born in 1937 and died in 2015) comes from interviews with her former accountant/business manager Jim Barbic and her cousin Dina Moore. “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” vaguely mentions that she moved to San Francisco as a teenager to become a famous entertainer, but leaves out details, such as she was born in Vallejo, California, and she dropped out of high school and started working as a cocktail waitress when she was 14.

It’s mentioned in the documentary that Doda’s parents (whose names and occupations are never mentioned in the movie) split up when she was 3 years old. Doda lived for a while with her mother, who is described as an abusive alcoholic. Doda was eventually sent to live at a Catholic school. Nothing is told in the documentary about her school years and what she was like back then.

Sometime in her 20s, Doda was married, divorced, and had two children (a son and a daughter), but she lost custody of the children. After she became famous, she often pretended that she was never a mother and avoided answering questions about if she was ever married. According to Moore, Doda’s ex-husband (whose name is not mentioned in the documentary) was abusive to Doda, who was left with longtime trauma from this abuse.

So much of Doda’s personal history isn’t explored at all in the documentary. Why did she lose custody of her children? Where are her children now? Who inspired her to become an entertainer? Did she get any early encouragement or discouragement to become an entertainer when she was a child? Did her personality change from her school days to when she became an entertainer? Don’t expect this documentary to answer any of those questions.

What “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” does instead is focus on her notorious antics that made her famous and have been described as trailblazing for exotic dancers. Whether or not she was a trailblazing feminist is open to debate. Doda certainly can be credited for leading the way in 1964 to make topless female dancing a big business in San Francisco, which was the first city in the United States to make it legal for businesses to have topless female workers. The businesses were often allowed to do it if the toplessness was labeled as entertainment for adults.

“Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” begins by describing how a San Francisco street named Broadway (in the city’s North Beach district) was the epicenter of San Francisco’s most popular nightclubs. In 1964, the Condor nightclub was co-owned by Gino Del Prete and Pete Mattioli. “Gino was wild and unpredictable,” says former Condor bartender Charlie Farrugia. By contrast, Pete Mattioli is described as the responsible and level-headed Condor business partner.

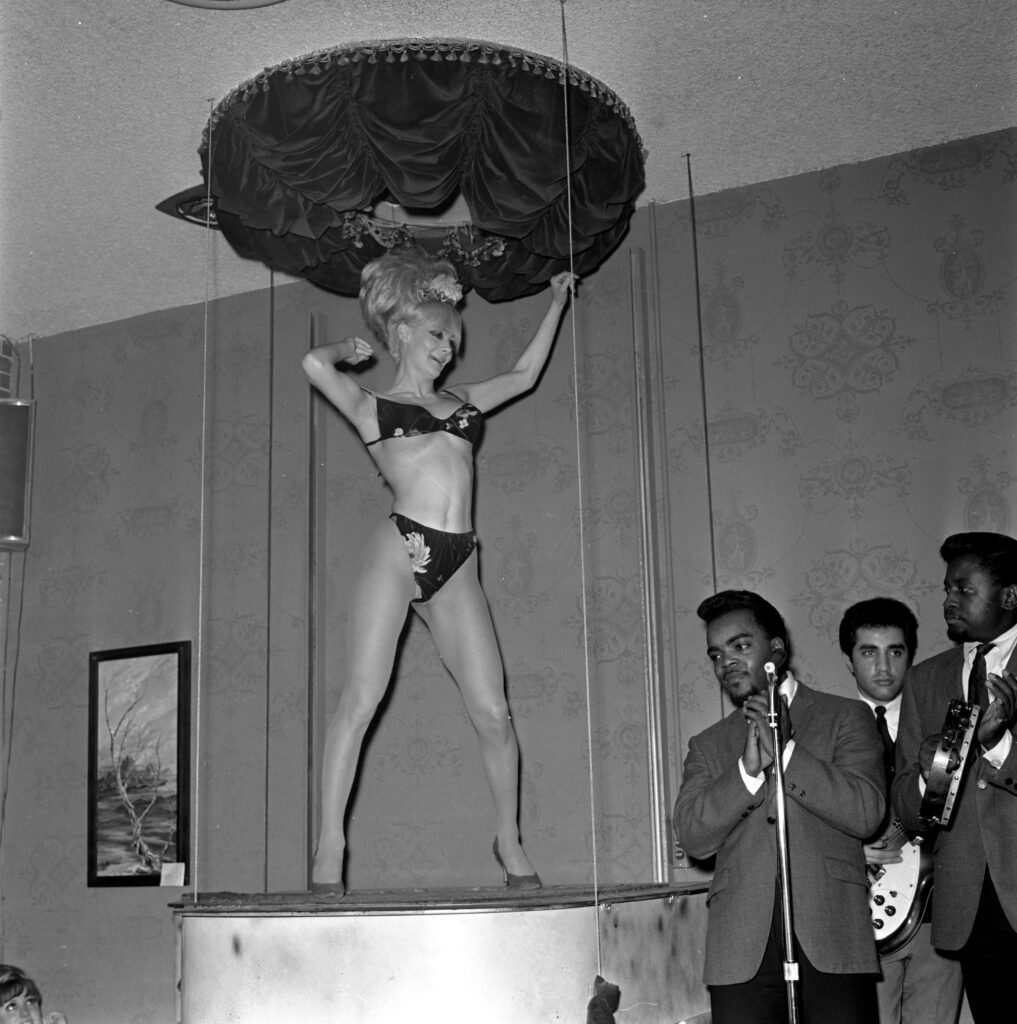

Doda started off as a cocktail waitress and then became a go-go dancer at the Condor. In 1964, R&B duo George & Teddy was one of the Condor’s biggest attractions. Doda began dancing The Swim (a 1960s dance craze where dancers mimicked swimming) on a piano during George & Teddy’s performances. And so, she became part of the George & Teddy act, every time George & Eddy performed at the Condor. The piano eventually was elevated and lowered from the ceiling, so Doda could make a dramatic entrance and exit on the piano.

Around the same time, fashion designer Rudi Gernreich invented the monokini: a topless swimsuit for women. If a bikini covered a female’s top and bottom, the monokini (held up by very thin straps) was designed to only cover a women’s bottom. Needless to say, in 1964, a monokini was considered edgy and controversial. Cultural critic/author Wednesday Martin, Ph.D., comments in the documentary. “The monokini, for me, really unlocks a deeper level of what Carol Doda was about and what she achieved.”

With the help of publicist David “Davey” Rosenberg (who died in 1986, at the age of 49), Doda decided to make a name for herself as America’s first famous topless dancer. On June 19, 1964, she wore a monokini while dancing. The Republican National Convention was happening in San Francisco at the same time as this milestone in the counterculture movement. Doda’s topless performance was an immediate hit and quickly led to sold-out performances with topless Doda as the headliner.

The topless women craze soon spread to other businesses in San Francisco, such as having topless waitresses, topless female sales clerks in retail stores and topless female shoe shiners. Because a business such as shoe shining is often conducted outdoors, the city officials began getting complaints about topless women being in public where children could see them. It led to a growing backlash against businesses that had topless women as part of the business.

In 1965, police took action when Doda, Del Prete, Pete Mattioli and several other topless dancers at the Condor were arrested for public indecency but were acquitted in a trial, because the prosecution could not prove there was a general consensus in the community that topless dancing was considered lewd and lascivious. The arrest brought even more fame to Doda, who was often described as a pioneer for female sexual liberation. Doda and other female Condor dancers were arrested again on public indecency charges in 1967, but the case never went to trial.

Always wanting to outdo herself, Doda then began dancing completely nude (and so did other dancers at the Condor) in 1969. By then, it was commonplace for semi-nude or completely nude dancers to be at adults-only clubs in many other American cities. Doda’s work at the Condor is considered to be the vanguard in making it legal to have nude dancing in these types of nightclubs in the United States. In 1972, California passed a law prohibiting bottomless nude dancing in businesses that served alcohol, which essentially ended Doda’s bottomless nude dancing career in California.

Part of Doda’s image was having large breasts, which she got through silicone injections. Her bra size went from 34B to 44DD. Her former accountant/business manager Barbic says that he warned Doda about the health risks of these silicone injections. “She kind of didn’t care,” Barbic comments in the documentary. “She was more interested in being an entertainer. And, of course, [Davey] Rosenberg was pushing her to do this.” Doda’s joking sexual double entendres and sarcastic wit in interviews, along with her “blonde bombshell” image, often got her compared to Mae West.

Several people in the documentary describe Doda as appearing to be very happy and extroverted when she was performing or doing interviews, but “the rest of the time, she was lonely and sad,” says Judy Mamou, a former Condor dancer, who claims to be the Condor’s second topless dancer. Judy Mamou (whose stage name was Tara) and her musician husband Jimi Mamou are interviewed in the documentary, which goes off on distracting tangents to give details about Judy’s topless act, her health problems from her silicone breast implants, and the the racism that the couple experienced because of their interracial marriage.

Judy Mamou gets a lot of screen time in this documentary, but even she admits she barely knew anything about Doda’s personal life, because she says that she and Doda usually only talked about work when they were hanging out together. Marsha McGovern, another former topless dancer, says about Doda: “She wasn’t open about her past at all. She never talked about her family.”

Phil Derdevanis, a former bartender at the Condor, says that in the 19 years he worked at the Condor, he never saw any of Doda’s family members. Jerry Martini, a former saxophonist for Sly and the Family Stone, seems to have only superficial knowledge of Doda, because he says in the documentary: “Carol Doda was friends with everybody.” Apparently, those friendships weren’t very deep, because she didn’t open about her private life to many people who describe themselves as her friends.

Squid B. Vicious, a musician, says he was an underage kid who was at the Condor on the night that Doda first went topless, because his father worked there as a musician. Vicious says he has a vivid memory of all the commotion that was caused by Doda’s performance (he says he did not see the actual performance), and he didn’t fully understand the impact of the performance until he was much older.

And what exactly is that impact? To its credit, “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” doesn’t shy away from discussing the pros and cons of this impact. Science journalist/author Florence Williams comments: “On the one hand, Carol Doda took the male gaze and twisted it to her own benefit. And she did well by that.”

Williams continues, “But what she couldn’t have anticipated is the legacy she would leave on women who then felt they needed to live up to this male gaze, which had been enhanced and exaggerated by the presence of these very large breasts. It’s a very particular lens through which to see beauty and through which to see sexuality, which ultimately has been very limiting and has led to some serious body dysmorphia in women to follow.”

Martin (who is Doda’s biggest cheerleader in the documentary) and former topless dancer Mary Ann Schildknect both claim that the type of nude dancing image that Doda had is empowering for women who want to express themselves in that way. Schildknect says when she moved to San Francisco as a young adult in the late 1960s, one of her goals was to fulfill her fantasy of being a stripper. She admits that most women do not consider being a stripper to be a dream job.

Schildknect says of the judgment she received from other people for being a topless dancer: “People would say, ‘Oh, that’s such a demeaning thing you’re doing.’ Well, if I’m not doing it, somebody else [will], and look at the money I’m making. What’s the big deal? It was great. Here I am, a woman. Give me your money.”

But, by Schildknect’s own admission, being a topless dancer wasn’t as liberating as it might have sounded. When all was said and done, the mostly male club owners (not the dancers) were the ones getting rich from the dancers’ work. In addition, there was a lot of discrimination going on: Small-breasted women found it difficult to get work as topless dancers, which is why many topless dancers have breast implants. In addition, Schildknect says that black women weren’t hired for these types of dancer jobs in major clubs until the 1980s.

Author/sociologist of culture Sarah Thornton, Ph.D., adds this perspective: “Topless clubs are a reflection of a patriarchal society. But that doesn’t mean there weren’t individual women who may very well find a very strong sense of empowerment for themselves in that environment.” Polly Mazza, who was a dancer/waitress at the Condor, says in the documentary that that being a dancer at the Condor didn’t feel like exploitation. “It felt like a job.”

For all the talk about Doda being a symbol of female empowerment, the documentary has plenty of details that Doda wasn’t as empowered as she wanted to be. She had many disputes with the Condor owners about being underpaid. Doda was also rejected when she tried to get an ownership stake in the Condor.

Doda quit the Condor several times in the 1970s and 1980s. She would go back to the Condor when her other career ventures flopped or job opportunities dried up in other areas. Eventually, she had to retire from dancing because she was considered too old for the job.

Her various other career ventures included acting, singing and hosting. She dabbled in doing phone sex for a job. She also started her own skin care line and clothing retail store. None of these jobs gave her long-lasting financial security. The documentary makes it clear that Doda (who was admittedly not very good when it came to handling her business matters) had financial struggles through her middle age and elder years.

Doda’s fake breasts—which were big reasons why she made money and why she became famous—weren’t exactly a great investment either. Her silicone implants leaked and caused her major health problems for the rest of her life. The way it’s described in the documentary, she probably would’ve lived longer if not for these health problems.

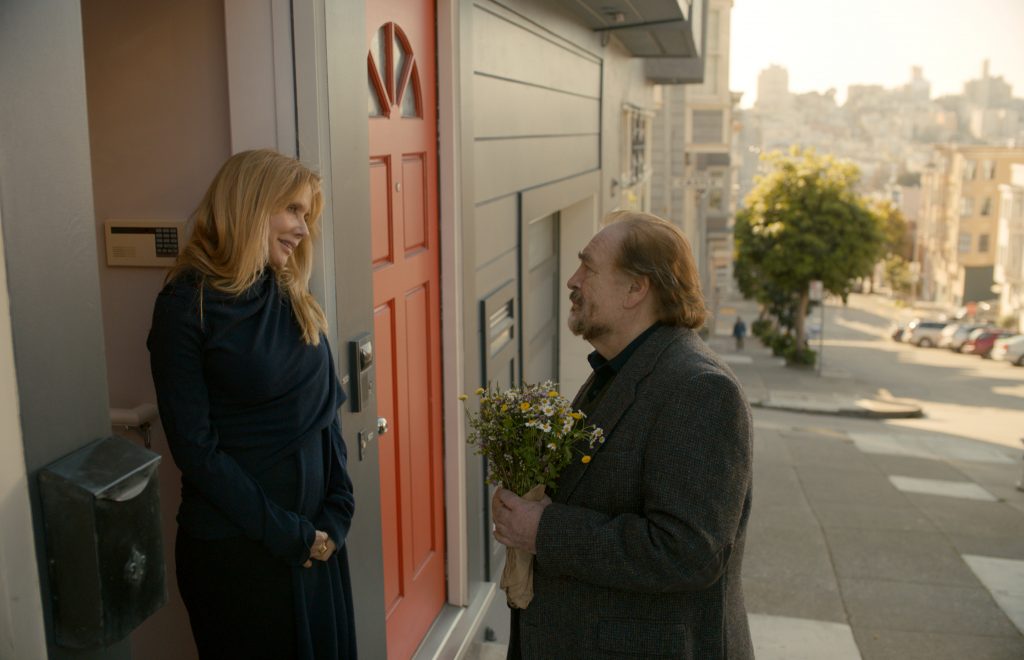

After being unhappy for so many years in her personal life, Doda had a 10-year romance with widower retiree Jay North—a former restaurant manager, photographer and journalist—who died in 2010, at the age of 77. Very little is revealed in the documentary about this part of Doda’s life. Charles North, Jay North’s son, is seen in a brief interview clip saying that his father and Doda were happy together and very devoted to each other. Doda’s cousin Moore says that Jay North was “the love of her [Doda’s] life.”

Other people interviewed in the documentary include former Condor bartenders George Faulkner and John Burton; Art Thanash, former owner of Roaring 20s, a rival nightclub to the Condor; former dancers Judy Mac and Pamela Rose; Doda’s friend Jeff Valkanoff; music historian Mike Boone; nightclub owner Jay Nelson; and attorney Rick Morse, who says that Doda had a passionate fling with Frank Sinatra in the 1960s.

Doda never lost her love of performing and remained an entertainer through the last year of her life. The movie ends with footage of her in 2015, performing “All of Me” at a small nightclub when she in very ill health and had lost most of her hearing abilities. Regardless of what people might think of Doda and how she influenced sexual liberation in the 1960s, there’s no denying that she had a zest for life that affected many people.

Picturehouse released “Carol Doda Topless at the Condor” in select U.S. cinemas on March 22, 2024, with an expansion to more U.S. cinemas on March 29, 2024.