March 26, 2018

by Carla Hay

The annual Cannes Film Festival in Cannes, France, is one of the world’s most prestigious film festivals, but Cannes Film officials have made two controversial decisions that could potentially alienate large segments of festival attendees and movie fans. First, movies that are from streaming services such as Netflix, Hulu or Amazon will no longer be eligible for awards at the Cannes Film Festival, such as the Palme D’or (the top prize), Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, etc. However, films from streaming services (and TV networks such as HBO) can still have screenings and premieres at Cannes. The second change, which is even more alienating to movie fans, is that the festival has now banned “selfies” from being taken on the red carpet. The changes go into effect for the 71st edition of the Cannes Film Festival, which takes place from May 8 to May 9, 2018.

In an exclusive interview with French magazine Le Film Français that was published on March 23, 2018, Cannes Film Festival director Thierry Fremaux explained that these changes have mostly to do with adhering to French laws which state that a movie that was originally released theatrically cannot be available for streaming in France until 36 months after the theatrical release. If streaming services such as Netflix release any of their movies in cinemas, it’s typically on the same day or within two weeks of the day it premieres on the streaming service. The new Cannes policy now requires that all films eligible for competition at the Cannes Film Festival must be available for release in French theaters, and the theatrical release of the movie must be before any release on TV or on streaming services. Since Netflix and other streaming services do not have business models that allow them to wait three years to stream their content in France in order to get a theatrical release in France, that leaves Netflix and other streaming services out of the loop to compete for awards at the Cannes Film Festival.

The United States and many other countries do not have laws mandating a three-year delay between when a movie is released in theaters and when it can be made available for streaming, which is why many critics of this Cannes policy think that the policy is out-of-touch and detrimental to a film festival that should pride itself on being a truly international event. However, those who agree with the Cannes policy believe that the festival has a right to support French cinema laws and preserve the specialness of a theatrical release.

In 2017, the Netflix films “Okja” and “The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)” premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Both films had a limited release in U.S. theaters, as did Netflix’s period drama “Mudbound” and sports documentary “Icarus,” which did not premiere at Cannes, but were nominated for Academy Awards because they met Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences requirements of being released in at least one U.S. cinema for a minimum of one week. (“Icarus” won the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, the first Academy Award won for a Netflix film.)

It will continue to be a complicated debate over whether or not a movie from a television network or a streaming service should be eligible for the same awards as movies that were first released in theaters, considering that Netflix, Amazon and other streaming services have become major presences at film festivals to acquire movies that have already been made and need distribution—as opposed to movies that were specifically made for the streaming services. For example, “Mudbound” and “Icarus” were two of several films that Netflix acquired after the movies premiered at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival.

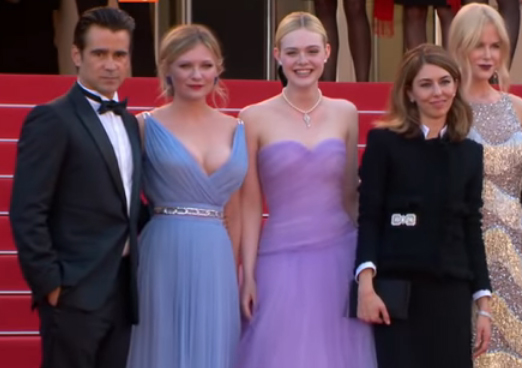

As for the ban on taking selfies on the red carpet, Fremaux told Le Film Français why Cannes officials made the decision: “At the top of the red carpet, the pettiness and the hold up caused by the untimely disorder created by taking selfies hurts the quality of the climbing of the steps … And it does the same to the festival as a whole.”

What’s bizarre about this ban is that while taking selfies are prohibited on the red carpet, autograph signing is apparently still allowed. Even if barriers were set up on the red carpet that would put a larger distance between celebrities and fans, there are still some celebrities and other people on the red carpet who will want to go over to fans and let them take pictures and get autographs. (And it could be argued that signing autographs take about the same time, if not more time, than taking selfies.)

Most people would agree that fan interaction is one of the main reasons why red-carpet premieres are exciting to attendees. The success of these types of events are largely dependent on the number of cheering fans who show up, and the fans are usually there to get photos and/or try to get autographs. So unless the Cannes Film Festival is planning to take away fans’ cell phones and cameras and push celebrities away who want to take photos with fans, this “no selfies on the red carpet” policy will be hard to enforce and probably won’t last.