May 20, 2021

by Carla Hay

“Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days”

Directed by Rebecca Gitlitz

Culture Representation: The documentary “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” features a racially diverse group of people (African American, white, Latino and Asian) discussing their connection to the groundbreaking children’s TV series “Sesame Street.”

Culture Clash: “Sesame Street,” which launched in 1969 on PBS, was the first nationally televised children’s program in the U.S. to be racially integrated, and “Sesame Street” has endured controversy over racial diversity, AIDS and representation of the LGBTQ community.

Culture Audience: “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in a comprehensive overview of “Sesame Street,” with an emphasis on how “Sesame Street” is responding to current global issues.

ABC’s documentary “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” offers some nostalgia for “Sesame Street” fans, but the movie is more concerned about how this groundbreaking children’s culture has made an impact around the world and with contemporary social issues. Directed by Rebecca Gitlitz, it’s an occasionally repetitive film that admirably embraces diversity in a variety of viewpoints. The major downside to the film is that it won’t be considered a timeless “Sesame Street” documentary, because the movie very much looks like it was made in 2020/2021. Therefore, huge parts of the movie will look outdated in a few years.

“Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” premiered on ABC just three days after director Marilyn Agrelo’s documentary “Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street” was released in select U.S. cinemas. “Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street,” which focused mainly on “Sesame Street’s” history from 1969 to the early 1990s, interviewed people who were “Sesame Street” employees from this time period, as well as some of the family members of principal “Sesame Street” employees who are now deceased. “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” takes a broader approach and includes the perspectives of not just past and present employees of “Sesame Street” but also several “Sesame Street” fans who are famous and not famous.

In addition, “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” (which was produced by Time Studios) makes a noteworthy effort to convey the global impact of “Sesame Street,” by including footage and interviews with people involved with the adapted versions of “Sesame Street” in the Middle East and in South Africa. “Sesame Street,” which is filmed in New York City, launched in 1969 on PBS. In the U.S., first-run episodes of “Sesame Street” began airing on HBO in 2016, and then on HBO Max in 2020. “Sesame Street” is now available in more than 150 countries.

“Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” quickly breezes through how “Sesame Street” was conceived and launched. There are brief mentions of “Sesame Street” co-creators Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett, but this documentary does not interview them. “Street Gang” has interviews with Ganz Cooney and Morrisett, who go into details about how they were inspired to create “Sesame Street” to reach pre-school kids, particularly African American children in urban cities, who had television as an electronic babysitter.

“Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days,” just like “Street Gang” did, discusses that the concept behind “Sesame Street” was to have a children’s TV show with a racially integrated cast and puppets, which were called muppets. A lot of research went into creating the show before it was even launched. The intent of “Sesame Street” was for the show to be educational and entertaining.

But the creators also wanted “Sesame Street” to include real-life topics that weren’t normally discussed on children’s television at the time. For example, when actor Will Lee, who played “Sesame Street” character Mr. Hooper, died in 1982, “Sesame Street” had an episode that discussed Mr. Hooper dying. “Sesame Street” did not lie to the audience by making up a story that Mr. Hooper had moved away or was still alive somewhere.

Time For Kids editorial director Andrea Delbanco says, “Many people avoid the topics that they know are going to be lightning rods. ‘Sesame Street’ goes straight for it. And they handle each and every one of them with the amount of thoughtfulness and research and care that they require.”

David Kamp, author of “Sunny Days: The Children’s Television Revolution That Changed America,” mentions that one of the reasons for the longevity of “Sesame Street” is the show’s ability to adapt to changing times: “They’ll pivot. They’ll adjust. They’ll say, ‘We got it wrong. Now, we’re going to get it right.’ That’s one of [the show’s] great virtues.”

One of the noticeable differences seen in comparing these two “Sesame Street” documentaries is how racial diversity has improved for “Sesame Street” behind the scenes. “Street Gang,” which focused on the first few decades of “Sesame Street” shows that although the on-camera cast was racially diverse, behind the scenes it was another story: Only white people were the leaders and decision makers for “Sesame Street” in the show’s early years. Several current “Sesame Street” decision makers are interviewed in “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days,” and it’s definitely a more racially diverse group of people, compared to who was running the show in the first two decades of “Sesame Street.”

Sonia Monzano, an original “Sesame Street” cast member (her character is Maria), says that although the show has always had a racially diverse cast, the muppets are the “Sesame Street” characters that people remember the most. “I remember my first scene with [muppet character] Grover,” Monzano comments with a chuckle. “It took me a while to be comfortable, not try to upstage them. And that’s the same with kids. You give them the platform. Get out of their way.”

As memorable as the “Sesame Street” muppets are, the human characters on the show had a particular impact on children, who saw “Sesame Street” people who reminded them of their family members or neighbors. Several celebrities who are interviewed in the documentary grew up watching “Sesame Street”—including Lucy Liu, Rosie Perez, Olivia Munn and Questlove—and they talk about the importance of seeing their lives and experiences represented on the show.

Perez comments on the show’s racial diversity: “We needed to see that, because when you’re a little girl in Brooklyn watching ‘Sesame Street,’ it’s nice to know that when you opened your door and walked down your stoop, you had the same type of people on your television.” Perez says about “Sesame Street’s” Maria character: “She was my Mary Tyler Moore,” and that until Maria came along, “Desi Arnaz Jr. was our only [Hispanic TV] role model for years.”

Racism, social justice and AIDS are some of the topics that “Sesame Street” has openly discussed over the years, sometimes to considerable controversy. But one topic was apparently too much to handle in “Sesame Street’s” first year: divorce. In “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days,” it’s mentioned that the original pilot episode of “Sesame Street” had a segment about muppet character Mr. Snuffleupagus dealing with his parents’ divorce. The “Sesame Street” executives did a test screening of this episode with children.

“The kids freaked out” because the idea of divorce was too upsetting for them, says Time staff writer Cady Lang. And the episode was “tossed out.” The documentary has some of this unaired Mr. Snuffleupagus “divorce” footage. In the documentary, Martin P. Robinson, the puppeteer and original voice for Mr. Snuffleupagus, expresses disappointment that this decision was made to eliminate talk of divorce on the first “Sesame Street” episode, because he says it was a missed opportunity for “Sesame Street” to start off with an episode that would have been very cutting-edge at the time.

However, there would be plenty of other episodes that would rile up some people. It’s not mentioned in the “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” documentary, but it’s mentioned in the “Street Gang” documentary that TV stations in Mississippi briefly wouldn’t televise “Sesame Street” in 1970, because they said people in their communities thought the show’s content was inappropriate. They denied it had to do with the show having a racially integrated cast. But considering that Mississippi was one of the last U.S. states to keep laws enforcing racial segregation, it would be naïve to think that racism wasn’t behind the “Sesame Street” ban.

The topics of racism and race relations take up a lot of screen time in this “Sesame Street” documentary, but mostly as pertaining to a contemporary audience, not the “Sesame Street” audience of past decades. Black Lives Matter protests and the racist murders of George Floyd and other African Americans have been discussed on “Sesame Street.” And there has been a concerted effort to have all races represented on “Sesame Street,” for the human cast members as well as the muppets.

Roosevelt Franklin (the first African American muppet on “Sesame Street”) was on “Sesame Street” from 1970 to 1975, and was voiced and created by Matt Robinson. The “Sesame Street” documentary briefly mentions Roosevelt Franklin, but doesn’t go into the details that “Street Gang” did over why the character was removed from the show: A lot of African American parents and educators complained that Roosevelt Franklin played too much into negative “ghetto” stereotypes. In the “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” documentary, musician Questlove and TV host W. Kamau Bell mention that they have fond memories of watching Roosevelt Franklin on “Sesame Street” when they were kids.

Although most muppets aren’t really any race, some of have been created to be of a specific race or ethnicity. Some muppets look like humans, while others look like animals. For the human-looking muppets, there have been Asian, Hispanic and Native American muppets in addition to the muppets that are presented as white or black people. And the documentary also gives significant screen time to Mexican muppet Rosita, a character introduced in 1991, which is considered a role model to many, particularly to Spanish-speaking people. Carmen Osbahr, the puppeteer and voice of Rosita, is interviewed in the documentary.

The documentary features a Mexican immigrant family called the Garcias, including interviews with mother Claudia and her autistic daughter Makayla, who are the only U.S. citizens of the family members who live in the United States. The Garcias say they love watching “Sesame Street” for Rosita, because she represents so many American residents who are bilingual in Spanish and English. Claudia Garcia, who moved from Mexico to the United States when she was 12, comments in the documentary: “When I was 12, it was not cool to speak Spanish. Now, it [the ability to speak Spanish] is a super-cool thing that you have.”

Four other diverse muppet characters are the Walker Family, an African American clan that is intended to be a major presence in contemporary “Sesame Street” episodes. Elijah Walker (a meteorologist) and his underage son Wesley, also known as Wes, have already been introduced. The characters of Elijah’s wife Naomi (a social worker originally from the Caribbean) and Elijah’s mother Savannah were being developed at the time this documentary was filmed. The documentary includes concept art for Naomi and Savannah.

According to Social Impact U.S. vice president Rocío García, “The Walker Family is a new family we’re creating for the racial justice initiative [Coming Together].” Wes and Elijah are characters that are supposed to contradict the media’s constant, negative narrative that black males are problematic. “Sesame Street” producer Ashmou Young describes the Wes Walker character as “a happy, energetic, innocent child who loves reading and architecture.” Elijah is a positive, intelligent role model. And no, he does not have an arrest record.

Bradley Freeman Jr., the puppeteer for Wes Walker, says in the documentary how proud he is to be part of this character, which he knows can be a role model for all children. “I was bullied at school for being black. That’s something that can hurt you, and you don’t know how to talk about it.” In “Sesame Street,” Elijah and Wes candidly discuss race issues and what it means to be an African American.

Omar Norman and Alisa Norman, an African American married couple, are in the documentary with their two daughters and discuss how the Walker Family on “Sesame Street” means a lot to them. Elder daughter Macayla says it’s impactful when Elijah talks to Wes about racism and how being a black male means being more at risk of experiencing police brutality. Omar gets emotional and tries not to cry when he thinks about how it’s sadly necessary for these topics to be discussed on a children’s show.

All the muppet characters were designed to not only teach kids (and adults) about life but also show what the world is all about and how to cope with problems in a positive way. Chris Jackson (who’s known for his role in the original Broadway production of “Hamilton”) talks about writing the song “I Love My Hair,” which debuted on “Sesame Street” in 2010. The song was written for any girl muppet to sing, but it has special significance to black girls because of how black females are judged the harshest by what their hair looks like. Jackson says that after he wrote the song, he thought, “I think I just wrote a black girl’s superhero anthem,” which he knows means a lot to his daughter.

And if some people have a problem with “Sesame Street” supporting the Black Lives Matter movement, well, no one is forcing them to watch the show. Kay Wilson Stallings, executive vice president of creative and production for Sesame Workshop, comments: “Following the murder of George Floyd, the company decided to make it a company-wide goal of addressing racial injustice [on ‘Sesame Street’].” U.S. first lady Dr. Jill Biden adds, “‘Sesame Street’ is rising up to the movement and addressing what’s going on and what kids are seeing and feeling around them.”

Wilson Stallings says, “We showed diversity, we showed inclusion, we modeled it through our characters. But you can’t just show characters of different ethnicities and races getting along. That was fine before. Now what we need to do is be bold and explicit.”

Sesame Workshop CEO Steve Youngwood comments on increasing “Sesame Street’s” socially conscious content: “We realized that nothing was hitting the moment the way it needed to be. And we pivoted to address it. The curriculum we developed is going to be groundbreaking, moving forward.”

LGBTQ representation on “Sesame Street” is still a touchy subject for people who have different opinions on what’s the appropriate age for kids to have discussions about various sexual identities. In 2018, former “Sesame Street” writer Mark Saltzman, who is openly gay, gave an interview saying that he always wrote muppet characters Ernie and Bert (bickering best friends who live together) as a gay couple. The revelation got mixed reactions. Frank Oz—the creator, original voice and puppeteer for Bert—made a statement on Twitter that Ernie and Bert were never gay.

Sesame Workshop responded with a statement that read: “As we have always said, Bert and Ernie are best friends. They were created to teach pre-schoolers that people can be good friends with those who are very different from themselves. Even though they are identifiable as male characters and possess many human traits and characteristics (as most ‘Sesame Street’ muppets do), they remain puppets, and have no sexual orientation.”

In retrospect, Sesame Workshop president Sherrie Westin says: “That denial, if you will, I think was a mistake.” She also adds that people can think of Ernie and Bert having whatever sexuality (or no sexuality) that they think Ernie and Bert have. As for LGBTQ representation on “Sesame Street,” Jelani Memory (author of “A Kid’s Book About Racism”) is blunt when he says: “It’s not enough.”

And it’s not just social issues that are addressed on “Sesame Street.” The show has also discussed health issues, such as the AIDS crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Although “Sesame Street” got pushback from some politically conservative people for talking about AIDS on the show, this criticism didn’t deter “Sesame Street,” which was supported by the majority of its audience for this decision. Dr. Anthony Fauci is in the documentary praising “Sesame Street” for helping educate people on health crises.

The documentary includes a segment on the first HIV-positive muppet Kami, a character in “Takalani Sesame,” the South African version of “Sesame Street.” Kami, who is supposed to be a 5-year-old girl, was created in 2002, in reaction to the AIDS epidemic in South Africa. Her positive outlook on life and how she is accepted by her peers can be viewed as having an impact that’s hard to measure.

Marie-Louise Samuels, former director early childhood development at South Africa’s Department of Basic Education, has this to say about Kami: “It wasn’t about her getting some sympathy. It was really about how productive she is in society with the virus.” Even though Kami was well-received in South Africa, “the U.S. was not as receptive,” says Louis Henry Mitchell, creative director of character design at Sesame Workshop.

Also included is a segment on Julia, the first autistic muppet on “Sesame Street.” It’s a character that is near and dear to the heart of Julia puppeteer Stacey Gordon, who tears up and gets emotional when she describes her own real-life experiences as the mother of an autistic child. Julia is one of several muppet characters that represent people with special needs. As an autistic child of a Mexican immigrant family, Makayla Garcia says in her interview that Rosita and Julia are her favorite muppets because they represent who she is.

The documentary shows how “Sesame Street” is in Arabic culture with the TV series “Ahlan Simsim,” which translates to “Welcome Sesame” in English. The Rajubs, a real-life Syrian refugee family of eight living in Jordan, are featured in the documentary as examples of a family who find comfort in “Ahlan Simsim” even though they’re experiencing the turmoil of being refugees. David Milliband, CEO of International Rescue Committee, talks about how “Sesame Street” being a consistent presence in children’s lives can help them through the trauma.

Other people interviewed in the documentary include Shari Rosenfeld, senior VP of international at Social Impact; Elijah Walker puppeteer Chris Thomas Hayes; Dr. Rosemarie Truglio, senior vice president of education and research at Sesame Workshop; Dr. Sanjay Gupta; Peter Linz, voice of muppet character Elmo; “Sesame Street” actor Alan Muraoka; Nyanga Tshabalala, puppeteer for the mupppet character Zikwe on “Takalani Sesame”; and former “Ahlan Simsim” head writer Zaid Baqueen. Celebrity fans of “Sesame Street” who comment in the documentary include Usher, Gloria Estefan, John Legend, Chrissy Teigen and John Oliver, who says about the show: “It was my first introduction to comedy, because it was so relentlessly funny.”

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCR) special envoy Angelina Jolie comments that The Count (the muppet vampire who teaches counting skills) is her favorite “Sesame Street” character: “He had a wonderfully bold personality: The friendly vampire helping you learn how to count. It worked for me.” Whoopi Goldberg adds, “All the things that ‘Twilight’ did for vampires, The Count did more. [The Count] made vampires cool because they could count.”

Jolie also comments on “Sesame Street’s” social awareness: “What they’re bringing is more relevant to today than ever.” The documentary includes 2021 footage of “Sesame Street” executives cheering when finding out that Sesame Workshop and International Rescue Committee won the MacArthur Foundation’s inaugural 100 and Change Award, a grant that gives the recipients $100 million over a maximum of six years.

There’s also a notable segment on the music of “Sesame Street.” Stevie Wonder (who has performed “123 Sesame Street” and “Superstition” on “Sesame Street”) performs in the documentary with a new version of the “Sesame Street” classic theme “Sunny Days.” The documentary has the expected montage of many of the celebrity guests who’ve been on “Sesame Street” too.

“United Shades of America” host Bell says that being asked to be on “Sesame Street” is a “rite of passage” for “famous people at a certain point. Got to get that ‘Sesame Street’ gig! That’s when you know you really made it: When ‘Sesame Street’ calls you.”

Although there’s a lot of talk about certain “Sesame Street” muppets, the documentary doesn’t give enough recognition to the early “Sesame Street” muppet pioneers who created iconic characters. The documentary briefly mentions Jim Henson (the creator and original voice of Kermit the Frog and Ernie), but Frank Oz (the creator and original voice of Grover, Cookie Monster and Bert) isn’t even mentioned at all.

Big Bird is seen but not much is said about Caroll Spinney, who was the man in the Big Bird costume from 1969 to 2018, and who was the creator and original voice of the Oscar the Grouch muppet. Spinney died in 2019, at the age of 85. Henson died in 1990, at age 53. Oz did not participate in the documentary.

The movie doesn’t mention the 2012 scandal of Elmo puppeteer Kevin Clash resigning from “Sesame Street” after three men accused him of sexually abusing them when the men were underage teenagers. The three lawsuits against Clash with these accusations were dismissed in 2014. Clash had been the puppeteer and voice of Elmo since 1984.

“Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” tries to bite off a little more than it should chew when it starts veering into discussions about United Nations initiatives and how they relate to “Sesame Street.” There’s no denying the global impact of “Sesame Street,” but “Sesame Street” is a children’s show, not a political science show about international relations. And some viewers might be turned off by all the talk about social justice content on “Sesame Street.”

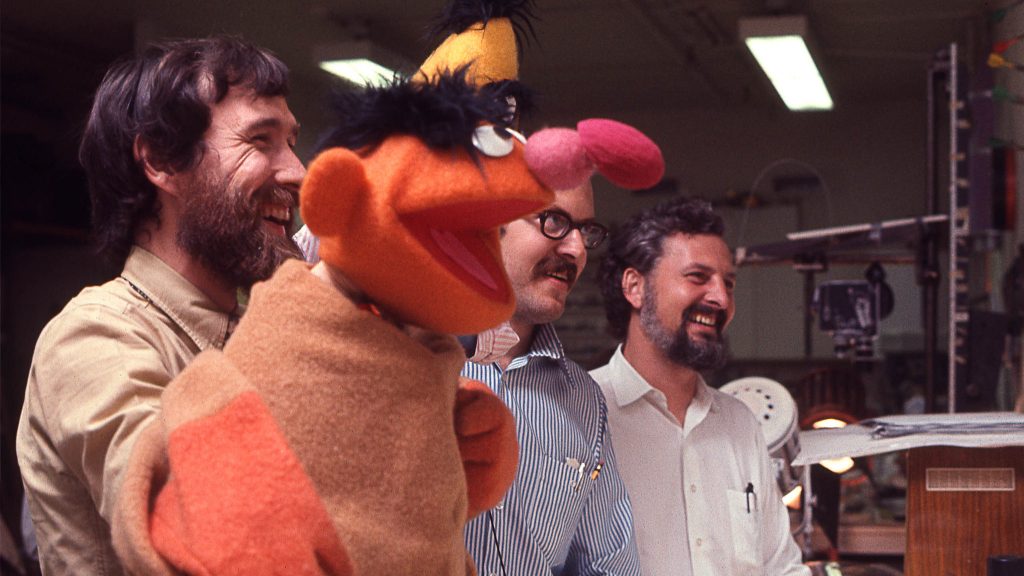

The documentary could have used more insight into the actual process of creating these memorable muppets. Except for some brief footage in a puppet-creating workspace, that artistic aspect of “Sesame Street” is left out of the documentary. Despite some flaws and omissions, the documentary is worth watching for people who want a snapshot of what’s important to “Sesame Street” in the early 2020s. Whereas “Street Gang: How We Got to Sesame Street” is very much about the show’s past, “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” tries to give viewers a glimpse into the show’s future.

ABC premiered “Sesame Street: 50 Years of Sunny Days” on April 26, 2021. Hulu premiered the documentary on April 27, 2021.