April 9, 2022

by Carla Hay

Directed by Jeff Fowler

Culture Representation: Taking place in Green Hills, Montana; Oahu, Hawaii; Seattle and various parts of the universe, the live-action/animated adventure film “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” features a nearly predominantly white cast of characters (with some African Americans and Asians) and representing the working-class and middle-class, along with some outer-space creatures.

Culture Clash: Sonic the Hedgehog battles again against the evil Dr. Robotnik, who wants to take over the world and gets help from Knuckles the Echidna, who is searching for the all-powerful Master Emerald.

Culture Audience: “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” will appeal primarily to fans of the video-game franchise and people who like high-energy, comedic adventures that combine live action and animation.

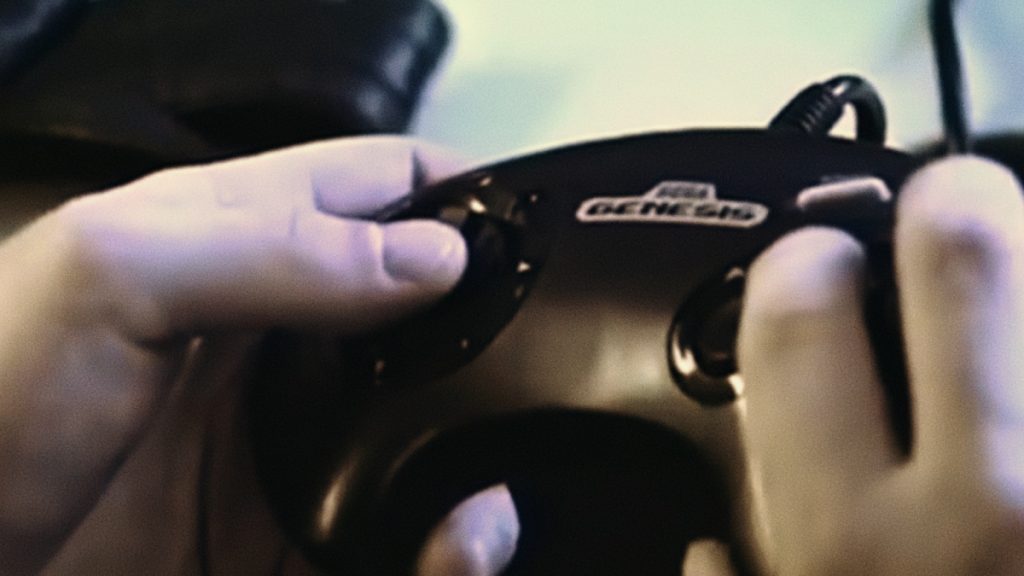

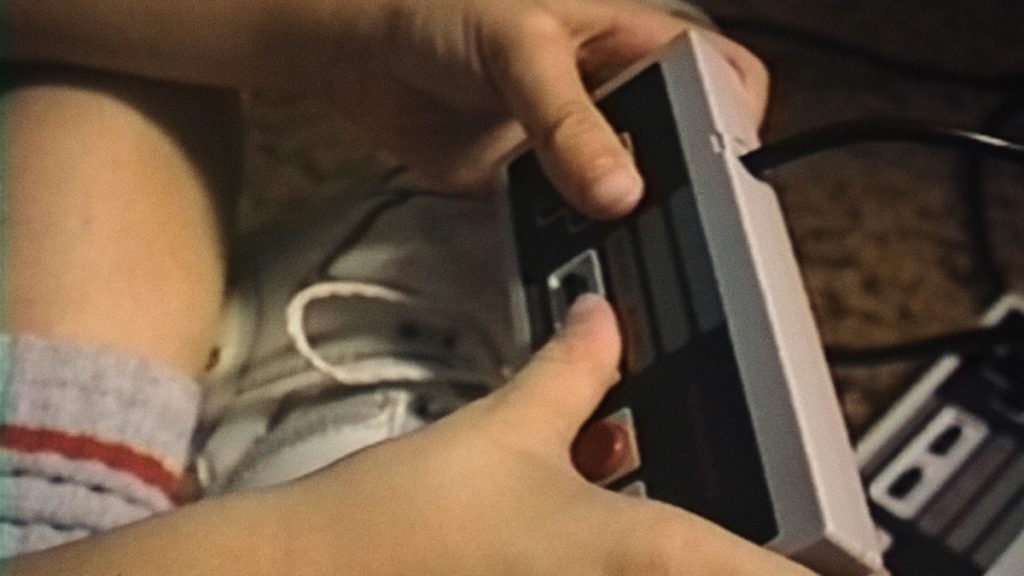

“Sonic the Hedgehog 2” does almost everything a sequel is supposed to do in being an improvement from its predecessor. While 2020’s “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie looked like a middling TV special, 2022’s “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” has a much more engaging story and more impressive visuals that are worthy of a movie theater experience. “Sonic the Hedgehog” panders mostly to children, while “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” is an adventure story with wider appeal to many generations. To enjoy “Sonic the Hedgehog 2,” you don’t have to be a video game player, and you don’t have to be familiar with Sega Genesis’ “Sonic the Hedgehog” video games on which these movies are based.

Several of the chief filmmakers from the “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie (including director Jeff Fowler) have returned for “Sonic the Hedgehog 2.” Pat Casey and Josh Miller, who wrote the “Sonic the Hedgehog” screenplay, are joined by John Whittington for the “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” screenplay. “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” has an obvious bigger budget than its predecessor, since the visual effects are far superior to what was in the first “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie. What hasn’t changed is that Sonic (voiced skillfully by Ben Schwartz)—a talking blue hedgehog who can run at supersonic speeds—is still a brash and wisecracking character with an unwavering purpose of doing good in the world.

Thankfully, “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” avoids the pitfall that a lot of sequels make when they assume that everyone watching a movie sequel has already seen any preceding movie in the series. It’s easy to understand “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” without seeing the first “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie. “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” also picks up where “Sonic the Hedgehog” left off: The evil Dr. Robotnik (played by Jim Carrey), Sonic’s chief nemesis, has been banished to the Mushroom Planet, where he has been isolation for the past 243 days.

The first “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie showed how Sonic was raised in another dimension by a female guardian owl called Longclaw (voiced by Donna Jay Fulks), a benevolent and wise character. When an apocalyptic disaster struck happened, Longclaw saved Sonic by opening up a portal to Earth and telling him that Earth would be Sonic’s permanent home. Longclaw also gave Sonic a bag of magical gold rings which could open portals and do other magic.

In the first “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie, Sonic settled in with happily married couple Tom Wachowski (played by James Marsden) and Maddie Wachowski (played by Tika Sumpter) in the fictional city of Green Hills, Montana. Tom is the sheriff of Green Hills, while Maddie is a veterinarian. Tom and Maddie also have a (non-talking) Golden Retriever named Ozzy, who is a friend to Sonic.

In the beginning of “Sonic the Hedgehog 2,” Sonic (who acts and talks like a human teenager) has been “adopted” by Tom and Maddie. Sonic sees himself as a hero who is on a mission to fight crime, just like Tom. However, Sonic’s efforts often lead to a lot of unintended wreckage.

The movie’s opening scene shows Sonic in Seattle, as he interferes in an armored car robbery taking place at night. When Sonic shows up, the car driver, who’s been taken hostage in the back, asks Sonic: “Why don’t you let the police handle it?” Sonic replies confidently, “Because that’s not what heroes do!”

It leads to a high-speed chase and car crashes, but thankfully no fatalities. The robbers are apprehended, but the Seattle Police Department is annoyed that Sonic’s excessive eagerness to stop the robbery and catch the criminals resulted in thousands of dollars in damages. All of this wreckage makes the news, so Tom inevitably finds that Sonic snuck out that night and went all the way to Seattle to be involved in these crime-stopping shenanigans.

Tom takes Sonic on a fishing trip on a small boat, where he lectures Sonic about being too reckless in Sonic’s attempts to be a big hero. Sonic gets defensive and says, “You’re supposed to be my friend, not my dad.” Tom looks a little hurt and miffed, but he and Sonic agree to a compromise that Sonic should be more careful if he ever gets involved in any more crime busting.

Sonic won’t have long to wait before he gets involved in something bigger than stopping an armored car robbery. Back on the Mushroom Planet, Dr. Robotnik has been biding his time by experimenting with mushroom juice. He says out loud to himself, “I’ve been striving to make funghi a functional drink of choice, with limited success.”

Dr. Robotnik has kept one of Sonic’s quills, which he finds out has magical energy, so Dr. Robotnik uses the quill as a conduit that summons up a portal that goes to another dimension. Just as Dr. Robotnik declares that he’s about to leave this “shiitake planet” (pun intended by the filmmakers), Echidna soldiers fly through the portal to the Mushroom Planet. The soldiers are soon followed by their red-colored leader: Knuckles the Echinda, who has superstrength in his fists. Knuckles (voiced by Idris Elba) is the guardian of the Master Emerald, a gemstone that controls the Chaos Emeralds, but Knuckles has lost the Master Emerald and is searching for it.

When Knuckles tells Dr. Robotnik about his quest, the evil doctor seizes the opportunity to get Knuckles’ help in going back to Earth to get revenge on Sonic and take over Earth. When Knuckles sees that Dr. Robotnik has Sonic’s glowing quill, Knuckles asks Dr. Robotnik where he got the quill. Dr. Robotnik says that he got it from Earth. “I’d be happy to show you the way,” Dr. Robotnik sneers before he and Knuckles enter the portal to go to Earth.

Eventually, Dr. Robotnik and Knuckles decide to team up so that they can both get what they want: Knuckles wants the Master Emerald to restore power to his tribe, while Dr. Robotnik wants revenge on Sonic and to take over Earth. Of course, a double crosser such as Dr. Robotnik can’t completely be trusted, but Knuckles needs Dr. Robotnik’s vast knowledge of Earth, which is a completely unknown and foreign planet to Knuckles.

Meanwhile, Tom and Maddie are leaving Sonic at home to take a trip to Oahu, Hawaii, for the wedding of Maddie’s older sister Rachel (played by Natasha Rothwell), a single mother who clashed with Tom in the first “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie. Rachel is marrying a man named Randall (played by Shemar Moore), who is completely devoted to her. Rachel’s daughter Jojo (played by Melody Nosipho Niemann), who’s about 11 or 12 years old, is the wedding’s ring bearer. Maddie is Rachel’s maid of honor.

Because of this trip, Sonic and his human family are not together as often as they were in the first “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie. It’s a refreshing departure that frees up Sonic to have some adventures on his own. While Maddie and Tom are in Oahu, Sonic is at home in Green Hills with the family dog Ozzy when Dr. Robotnik shows up at the door.

In “Sonic the Hedgehog 2,” Sonic also meets a new ally coming from another universe: Miles “Tails” Prower (voiced by Colleen O’Shaughnessey), an adolescent, two-tailed yellow fox who hero worships Sonic. Tails becomes a major asset in the battle against Knuckles and Dr. Robotnik.

Two supporting characters from the first “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie return in this sequel and continue their roles as being some of the comic relief: Stone (played by Lee Majdoub), a former government agent, is an obsessively loyal assistant to Dr. Robotnik. Wade Whipple (played by Adam Pally) is the deputy sheriff of Green Hills. Both are essentially buffoon characters. Stone is seen working as a barista at a place called the Mean Bean Coffee Co. when he ecstatically finds out that Dr. Robotnik has returned to Earth.

The “race against time quest” in this movie takes Sonic to various places, ranging from a dive bar filled with Russian-speaking, rough-and-tumble characters; a ski slope for an adrenaline-packed chase on snowboards; and Oahu for the wedding. Because “Sonic the Hedgehog” has a lot of comedy, you can bet that there will be mishaps that this wedding, where Rachel hilariously turns into a “bridezilla” when things go wrong.

“Sonic the Hedgehog 2” seems to be more mindful than the first “Sonic” movie that much of this movie franchises’ target audience consists of adults who remember when the “Sonic the Hedgehog” video games first became popular in the early 1990s. Therefore, this sequel has more pop-culture jokes that adults are more likely than children to understand. The wedding scenes are almost a spoof of wedding scenes in romantic comedies, while Rachel turning into a “bridezilla” will look familiar to anyone who knows about the reality series “Bridezillas.”

At one point in the movie, it’s mentioned that owls and echidnas have been fighting each other for centuries. Sonic then quips, “Like Vin Diesel and the Rock.” In another scene, Dr. Robotnik tells Knuckles of their shaky alliance: “You’re as useful to me now like a backstage pass to Limp Bizkit.” People who know about rock band Limp Bizkit’s peak popularity in the late 1990s/early 2000s are most likely to understand that joke. Carrey’s gleefully over-the-top performance as Dr. Robotnik is reminiscent of his rubber-faced, mugging-for-the-camera roles that made him a star in the 1990s.

Sometimes, sequels can be hindered by introducing too many new characters in the story. However, Knuckles is a welcome addition, since his character is one of the best things about “Sonic the Hedgehog 2,” with Elba diving into the role with gusto. Knuckles is a pompous know-it-all who feels out of his element because he doesn’t know much about Earth. Much of the comedy about Knuckles is when his ignorance about Earth is showing, and he tries to hide his embarrassment with more ego posturing.

The character of Tails also brings some more personality to this movie franchise. Tails is the perfect complement to Sonic, who likes feeling as if he can mentor someone. Depending on your perspective, O’Shaughnessey’s voice makes Tails sound androgynous or like a boy whose voice hasn’t reach puberty yet. The movie has a mid-credits scene that shows another well-known character from the “Sonic the Hedgehog” video games will be introduced in the third “Sonic the Hedgehog” movie.

The pace of “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” is very energetic without rushing the plot too much. “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” is a two-hour movie that could have edited out about 15 minutes, but the two-hour runtime will fly by pretty quickly because the movie doesn’t get too boring. This is not a movie with any big plot twists or major surprises, but it fulfills its purpose of being family-friendly entertainment that might pleasantly surprise viewers who normally don’t care about movies based on video games.

Paramount Pictures released “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” in U.S. cinemas on April 8, 2022. The movie will be released on digital, VOD and Paramount+ on May 24, 2022. “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” is set for release on 4K Ultra HD, Blu-ray and DVD on August 9, 2022.