September 9, 2020

by Carla Hay

“All In: The Fight for Democracy”

Directed by Liz Garbus and Lisa Cortés

Culture Representation: Taking place in various parts of the United States, the political documentary “All In: The Fight for Democracy” features a racially diverse group of people (African American, white, Latino, Asian and Native American) discussing past and present issues in U.S. citizens’ right to vote.

Culture Clash: The consensus of people interviewed in the documentary is that voting inequalities, such as voter suppression and gerrymandering, stem from party politics and bigotry issues against people of color, young people and people who are economically disadvantaged.

Culture Audience: “All In: The Fight for Democracy” will appeal primarily to people who have liberal-leaning beliefs, since conservative lawmakers are portrayed as the chief villains who want to suppress people’s votes.

The political documentary “All In: The Fight for Democracy” (directed by Liz Garbus and Lisa Cortés) examines the history of voting rights in the United States and how those rights have been violated. It’s a subject that’s theoretically supposed to be a non-partisan issue, but the documentary doesn’t try and hide that it’s biased heavily toward liberal politics and the Democratic Party, which is portrayed as the political party that’s taking the most action to include more U.S. citizens in the voting process. When it comes to modern-day voter suppression and the push to exclude people from the voting process, the documentary puts the blame primarily on Republican politicians and other lawmakers who have conservative-leaning political beliefs.

Democratic politician Stacey Abrams is one of the producers of “All In: The Fight for Democracy,” so it’s no surprise that she’s the main star of the movie, which uses her highly contested 2018 political campaign for governor of Georgia as an example of voter suppression. Her opponent in that campaign was Republican politician Brian Kemp, who was Georgia’s secretary of state in charge of overseeing the voting process in Georgia while he was campaigning for governor. Overseeing the voting process in his own election was an obvious conflict of interest, but Kemp refused to step down from his secretary of state position during his gubernatorial campaign because it was legal in Georgia for him to keep that position while he was campaigning for another office.

In the end, after 10 days of the election results being contested, Kemp was declared the winner with 50% of the votes, while it was announced that Abrams received 49% of the votes. The controversial election resulted in Abrams and her political group Fair Fight filing lawsuits and investigating reports of widespread voter suppression and other tactics to prevent thousands of people in Georgia from voting. The accusations are that this voter suppression has disproportionately affected districts with voters who are registered Democrats and/or people of color. The racial elements of this election could not be ignored, since Abrams would have been the first African American woman to be a state governor in the U.S. if she had won the election.

Critics of Abrams have called her a “sore loser,” but there is a valid argument in wondering what the outcome of that election would have been if thousands of voter registrations hadn’t been mysteriously purged from computer systems. There were also confirmed reports of thousands of voter registrations not being processed in time for the election, mostly in areas of Georgia where there is a high percentage of people of color and/or registered Democrats. It also looked suspicious that most of the voting sites that were permanently shut down in Georgia were in districts with a high percentage of people of color and Democrats.

Even though Abrams gets the most screen time in this documentary, the entire film isn’t “The Stacey Abrams Show,” because most of the film is about the history of U.S. citizens’ right to vote and some of the recurring problems in the U.S. voting process. Abrams’ family background is mentioned (she’s the second-oldest of six kids, raised primarily in Mississippi and Georgia), and her parents Robert and Carolyn Abrams (who are both ministers) are interviewed in the film. The documentary also includes the 1993 footage of Abrams (when she was a 19-year-old student at Spelman College) speaking at the 30th anniversary of the March on Washington. Coming from a family that placed a high value on education, religion, voting and public service, it’s no wonder that she wanted to go into politics.

The first half of “All In: The Fight for Democracy” takes a look at the long history of voter exclusion and suppression in the United States, before the civil-rights movement of the 1960s, and how certain groups of people have constantly had to fight for their right to vote. The second half of the documentary focuses primarily on U.S. voting rights during and after the 1960s civil-rights movement. As historian/author Carol Anderson comments in the documentary: “Past is prologue. Those forces that are systemically determined to keep American citizens from voting, they have been laying the seeds over time.”

It’s mentioned in the documentary that when George Washington was elected the first president of the United States in 1789, only 6% of U.S. citizens had the right to vote. These citizens were white male property owners. The documentary does an excellent job of retracing how laws gradually changed for voting to open up to more U.S. citizens, so that property ownership wasn’t a requirement to vote and U.S. citizens who weren’t white men got the right to vote. The 15th Amendment (which, in 1870, gave U.S. citizens the right to vote regardless of their race, color or previous condition of servitude), the 19th Amendment (which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920) and the Voting Rights Act (originally signed into law in 1965) are three of the most important legislations to make these voting rights possible.

The documentary reiterates that the biggest injustices in voting often stem from racism. After the slaves were freed, the U.S. experienced the Reconstruction period when, for the first time in U.S. history, African American men began to own property and held elected offices on the federal and state levels. But, as “Give Us the Ballot” author Ari Berman says in the documentary: “The greatest moments of progress are followed by the most intense periods of retrenchment.”

In other words, when people of color are perceived as advancing too far in American society, there’s political backlash. The Reconstruction period led to the shameful Jim Crow period, particularly in Southern states, which passed racial segregation laws making it more difficult for people of color to access the same levels of education and resources as white people. Poll taxes and literacy tests became requirements to vote and were used as a way to weed out poor and uneducated people, who were disproportionately people of color. Black men in particular were singled out for arrests for minor crimes (such as loitering), and these arrest records were used as reasons to prevent them from voting in certain states.

The Florida felony disenfranchisement law of 1868 created a trend of felons being barred from voting. The U.S. is currently the only democracy that doesn’t allow convicted felons to vote. Critics of this voter exclusion law say that it’s inherently racist because people of color are more likely to be convicted of the same felonies that white people are accused of committing. Efforts to repeal the “felons can’t vote” laws are mentioned in the documentary, which includes an interview with Desmond Meade of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition.

The documentary also mentions that before the civil rights movement of the 1960s, it could be dangerous and sometimes deadly for African Americans and other people of color who voted. African Americans and other people of color could get fired for voting if they had a racist employer. Depending on the area, African Americans and other people of color would be the targets of violence if they voted. And even registering to vote could be an ordeal, since it was common in certain areas for intimidation tactics to be used on people of color during voter registration.

The documentary names Maceo Snipes (an African American military veteran) as an example: In 1946, Snipes was murdered because he defied segregation laws and was the only African American to vote in Georgia’s Democratic primary election. Abrams shares a story that her grandmother Wilter “Bill” Abrams told her about being terrified the first time that she voted, because Wilter was afraid that she would be attacked by white racists at the voting site. Wilter was eventually persuaded to vote by her husband, who reminded her of the people who sacrificed their lives to give people of color the right to vote in America.

“All In” also details how other racial groups have been the targets of voter exclusion in U.S. history. In its early years, California resisted laws to allow Chinese people and other Asians to vote. States near the Mexican border, particularly Arizona and Texas, have a long history of trying to exclude Latinos and Native Americans from voting. In many situations, people were kept from voting if English was not their first language. The United States does not have an official language, and there’s nothing in the U.S. Constitution that says U.S. residents and U.S. voters are required to speak English.

According to several people in the documentary, the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections of Democratic politician Barack Obama (the first African American president of the United States) sparked a backlash that led to an increased push by conservative lawmakers to erode the Voting Rights Act. In 2013, a conservative majority in the U.S. Supreme Court decided in the Shelby County v. Holder case that voting laws could revert back to the individual U.S. states. This Supreme Court ruling opened up a floodgate of states (usually in the South and Midwest) that revised their voting laws that critics say make it easier for these states to allow voter suppression.

Historian/author Anderson doesn’t mince words about these revised voting laws that began in the 2010s: “It’s Jim Crow 2.0.” Gerrymandering and voter suppression are described in the documentary as two sides of the same coin. The documentary reiterates the warning that voter manipulation usually targets people of color, poor people and young people. And because most people of color who are U.S. citizens tend to be Democrats, the documentary implies that corrupt Republicans are behind a lot of the voter suppression when it comes to people of color.

Voter suppression comes in three main forms: strict voter ID laws, voting roll purges and permanent closing of voting sites. Critics say that voter ID laws are designed to exclude poor and uneducated U.S. citizens who might not have government-issued IDs. Voting roll purges (eliminating voter registrations) are often done without voters’ knowledge and permission, and are usually because the eliminated voters haven’t voted for a number of years or for other random reasons. And permanent closures of voting sites have been found to occur mostly in economically disadvantaged areas where there’s a large percentage of people of color.

In many cases, even if a voter has a government-issued ID, the voter can be turned away at the voting site if the voter’s signature is not an exact match to the signature that the voter has on file with the board of elections office. In the documentary, Sean J. Young of ACLU Georgia says signatures that don’t match are big issues with Asian immigrants, who often have an Asian first name and an American first name. Barb Semans and OJ Semans of Four Directions (a voting-rights group for Native Americans) mention that North Dakota’s voting law requiring a residential address for registration excludes numerous Native Americans who have to use post-office boxes because they live on reservations without residential addresses.

Alejandra Gomez and Alexis Delgado Garcia of Lucha (a voting-rights groups for Latinos) are featured in the documentary. Garcia is seen approaching different people in Latino communities with voter registration information and encouragement to vote. The results are mixed. Some of the people aren’t U.S. citizens and therefore aren’t eligible to vote, while the U.S. citizens are either interested in registering and plan to vote, or are reluctant to register because they don’t like or trust politicians. Gomez comments, “The most important part of voter registration is that human connection and being able to understand why that person does not trust.”

Abrams says in the documentary: “When entire communities become convinced that the process is not for them, we lose their participation in our nation’s future. And that’s dangerous to everyone.” Eric Holder, who was U.S. attorney general in the Obama administration, comments: “Too many Americans take for granted the right to vote and don’t understand that unless we fight for the right to vote, unless we try to include as many people as possible, our democracy is put at risk.”

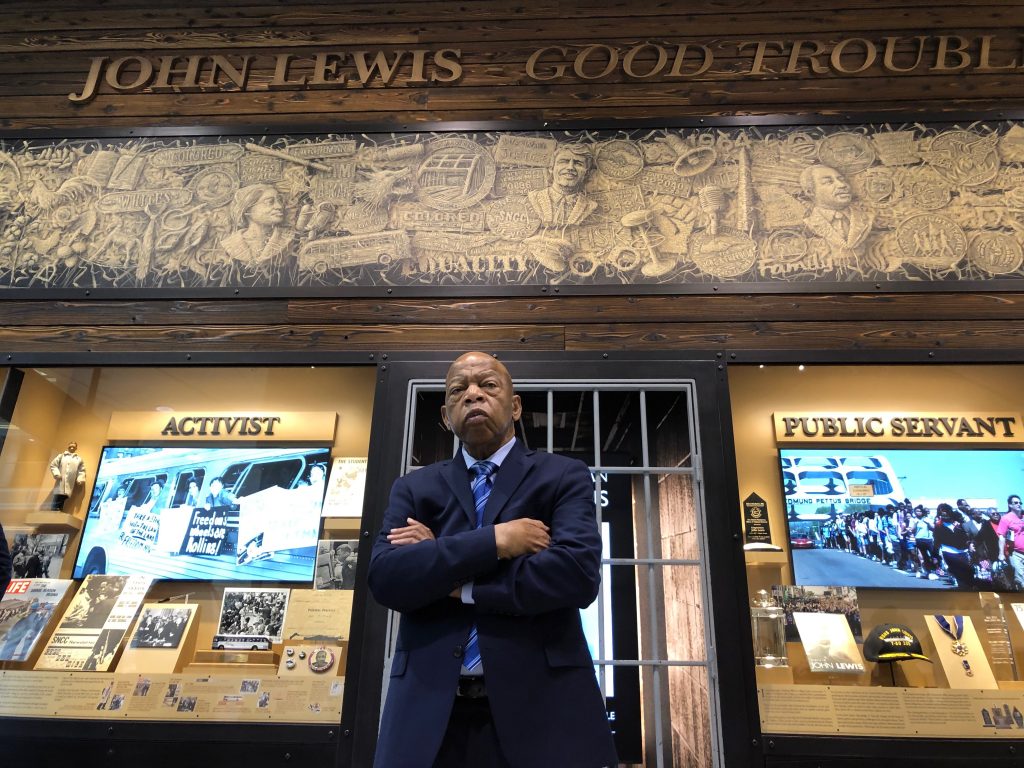

Other people interviewed in the documentary include Michael Waldman of the Brennan Center for Justice; historian/author Eric Foner; civil-rights leader Andrew Young; civil-rights attorney Debo Adegbile; Kristen Clarke of Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law; David Pepper, chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party; Lauren Goh-Wargo, Abrams’ former campaign manager; Luci Baines Johnson, daughter of former U.S. president Lyndon Johnson, who signed the Voters Right Act into law; Ohio U.S. Representative Marcia Fudge; and student activists Michael Parsons (from Dartmouth College) and Jayla Allen (of Prairie View A&M University).

This documentary is obviously stacked with people who are open with their politically liberal beliefs and who are known Democrats. There’s some attempt to present conservative points of view, but not much. One of the conservative-leaning people interviewed in the documentary is attorney Bert Rein, who represented Shelby County, Alabama, in the Shelby County v. Holder case. He doesn’t say much except that he thought that the case was legally compelling enough for him to want to represent Shelby County.

Hans Von Spakovsky of the right-wing Heritage Foundation, which is a major advocate of voter ID laws, is also interviewed in the documentary. He says that the “vast majority” of people in the United States believe in voter ID laws, although he doesn’t list any sources or details as the basis for this statement. Considering that the documentary describes voter suppression and gerrymandering as being perpetrated mostly by corrupt Republicans, it’s not too surprising that a documentary with a Democratic politician (Abrams) as one of the producers is not going to give much of a voice to the opposition.

Even with this blatant bias, “All In” could have done a better job at looking at other cases of suspected voter suppression besides Abrams’ 2018 gubernatorial election campaign. Because the documentary presents Abrams’ case as the only major example of suspected voter suppression, it undermines the documentary’s message that voter suppression is a widespread problem. A skeptic could easily say that the Abrams/Kemp campaign controversy was a rare fluke. It also would have been interesting to see more of what Fair Fight is doing behind the scenes to prevent voter suppression.

And there could have been more of an exploration of how votes are manipulated in ways other than voter suppression. For example, there’s no mention in the documentary about how computer hacking affects voting machines that process data via computers. (The excellent HBO documentary “Kill Chain: The Cyber War Over America’s Elections” examines this cyberhacking topic in depth.) And there is growing concern over how governments from outside the U.S. could be corrupting the U.S. electoral system to influence the votes of U.S. citizens.

The documentary also should have had more interviews with people who work on the “front lines” of voting, such as polling workers and officials who work for boards of elections. There’s a definite “liberal elitism” tone to this documentary, because of the numerous Democratic politicians and liberal attorneys who are interviewed. And during the end credits of the film, several celebrities who are outspoken liberals (such as Gloria Steinem, Constance Wu, Jonathan Van Ness, Gabourey Sidibe, the Jonas Brothers and Yara Shahidi) give soundbites telling people their voting rights.

“All In” makes its liberal bias abundantly clear, but people of any political persuasion can appreciate that the documentary has a superb overview of the history of voting in the U.S. and explains how people can be more informed voters. The documentary doesn’t sugarcoat that there are massive inequalities in people’s voting experiences in the U.S., and many of the problems are rooted in racism and other prejudices. It’s this history lesson and encouragement of more awareness for voter rights—rather than the partisan posturing and finger-pointing—where “All In” shines the most.

Amazon Studios released “All In: The Fight for Democracy” in select U.S. cinemas on September 9, 2020. Amazon Prime Video will premiere the movie on September 18, 2020.