February 4, 2020

by Carla Hay

Directed by Horace B. Jenkins

Culture Representation: Set in 1981 Louisiana, the romantic drama “Cane River” has a predominantly African American cast of working-class and middle-class characters.

Culture Clash: Creoles and darker-skinned African Americans have conflicts that stem from issues of colorism and classism within the community.

Culture Audience: “Cane River” will appeal primarily to people who want to seek out vintage African American independent films or independent films about Louisiana culture.

“Cane River” is a throwback to a time when a romantic movie drama starring African Americans didn’t keep repeating negative stereotypes, such as excessive cursing, someone facing prison time (or someone who just got out of prison) and someone who’s been caught cheating on a partner. “Cane River” was written, directed and produced by Horace B. Jenkins, who passed away of a heart attack at the age of 42 in 1982, before the movie could be released. “Cane River” has received a new 4K restoration from IndieCollect, in association with Academy Film Archive, and it’s being released for the first time in 2020.

The movie is very much a snapshot of African American independent cinema in the early 1980s. Don’t expect to see anything that could be called masterful filmmaking, but just go along for the retro ride for this simple story that portrays a very complex issue that’s rarely discussed in movies: colorism among African Americans and how it can divide black people for generations.

At the beginning of the movie, it’s May 1981, and tall and good-looking Peter Metoyer (played by Richard Romain) is traveling by bus to go back to his rural hometown of Natchitoches, Louisiana. Based on the warm welcome he gets when he arrives ( a crowd has gathered and there’s a “welcome home” banner in the center of the town), he seems to be somewhat of a local hero. Peter is known in the area because he was a superb athlete in high school, with football the sport he excelled in the most. He was so talented that he spent some time away from home being courted by professional football teams, including the New York Jets.

But Peter is far from a typical athlete. He turned down all the offers, and instead decided to move back to his small town to become a farmer and a poet. His Creole family owns farming land that he plans to live on and harvest for a living while pursuing his writing career.

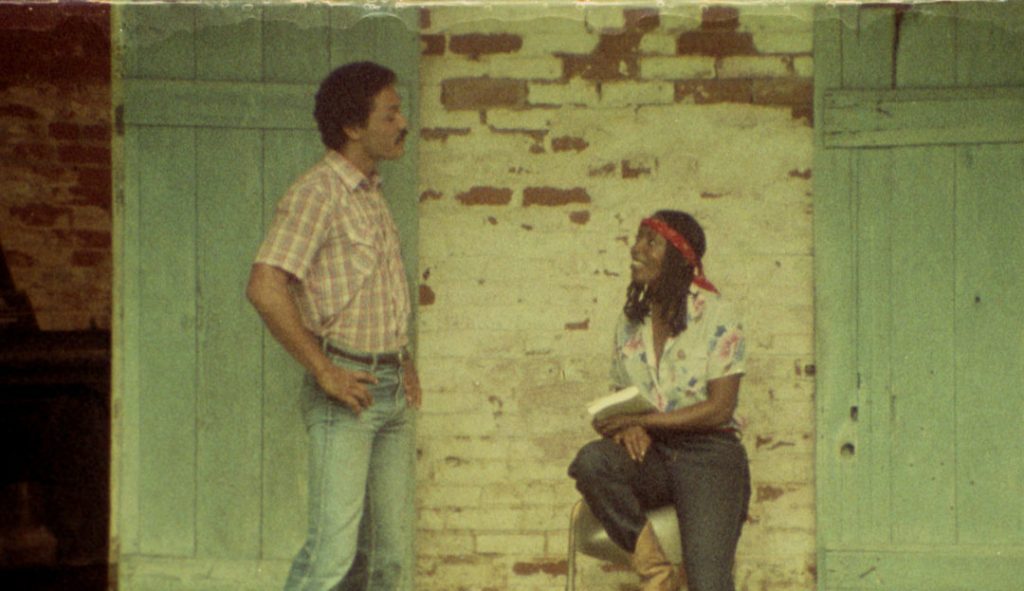

While getting himself re-acquainted with his hometown, he visits the Melrose Plantation, where he meets a tour guide named Maria Mathis (played by Tommye Myrick), a sassy and intelligent woman who has ambitions to go to college. Peter and Maria, who are both in their early 20s, hit it off immediately, and Peter offers her a ride home—by horseback. (There just happens to be two horses nearby that he can use.)

Of course, it wouldn’t be a romantic drama without the central couple having some obstacles. As soon as Peter meets Maria, it’s obvious that their lives are going in different directions. She’s tired of living in a small town and is looking forward to moving to the big city of New Orleans, where she’ll start attending Xavier University of Louisiana in the fall. Meanwhile, Peter has already experienced living in a big city, and he wants to go back to living on his family farm.

Despite knowing that they have limited time to spend with each other before Maria has to leave for college, Peter and Maria start dating each other. They go horseback riding, swimming and have other romantic meet-ups near Cane River. Peter and Maria start to fall in love, even though they both know that the circumstances are less than ideal for them.

And there’s another problem: Maria’s domineering, widowed mother Mrs. Mathis (played by Carol Sutton) and her surly, slacker brother (who doesn’t have a name in the movie and is played by Ilunga Adell) disapprove of the relationship from the beginning because the Metoyer family has a Creole image of being prejudiced against darker-skinned African Americans who are poor or working-class. As a reference for their beliefs, Maria’s mother and brother cite the findings of the 1977 non-fiction book “The Forgotten People: Cane River’s Creoles of Color Book,” by Elizabeth Shown Mills and Gary B. Mills. The book’s historical account of Creoles in the area lists an ancestor of Peter’s as being a free woman of color who married a white man who owned slaves.

Maria’s mother and brother believe that their family members are descendants of people who used to be slaves of the Metoyer family. It’s one of the main reasons why Maria’s mother and brother are vehemently against Maria having a romance with Peter. They also believe that Maria will never truly be accepted by the Metoyers since she’s not a light-skinned Creole. Maria angrily brushes off their orders to stop seeing Peter, because she thinks that he and the current Metoyer family shouldn’t be held responsible for what happened hundreds of years ago.

In defiance of her family’s disapproval, Maria continues to see Peter and eventually meets his family—including his father (played by Lloyd LaCour) and his sister Dominique (played by Barbara Tasker), who mostly approve of the relationship. However, Peter’s family members have concerns that Peter’s relationship won’t last since Maria will be going away to New Orleans for college, and they don’t want Peter’s heart to get broken.

As Maria and Peter fall deeper in love, they impulsively take a trip to New Orleans, but the trip further amplifies their contrasting goals and interests. While Maria is fascinated by the big city and can’t wait to go back, Peter is reminded of why he wants to live on a farm instead of a big city. However, his whirlwind romance with Maria has become very serious because he’s thinking about proposing to her and asking her to stay in Natchitoches with him. He starts to drop hints to Maria that maybe she should think twice about going to Xavier University and maybe attend a college that’s closer to Natchitoches. When Maria starts to doubt her decision to go to Xavier, her mother is infuriated, and Maria eventually has to make a decision once and for all about what she’s going to do.

For all of its charm and sincerity, “Cane River” does have some noticeable flaws, especially with its choppy editing (there are some really cringeworthy jump cuts) and uneven sound mixing. Myrick and Romain, who made their film debuts in “Cane River,” make a believable on-screen couple but their performances would have been better if they had more acting experience. And quite a few of supporting actors are also a little too stiff in their performances.

The movie is very low-tech, but it has a lot of heart that shines through in the story. The cinematography by Gideon Manasseh captures some great shots of the Cane River landscape. And for people who like old-school R&B, the movie’s soundtrack by LeRoy Glover will be a nostalgic treat.

Amid the romantic plot, there’s also a message in the movie about the repercussions of colorism and how it still affects people, generations after slavery was abolished in the United States. Even among African Americans and other black people, lighter-skinned black people can get preference over darker-skinned black people, which can cause deep-seated resentments that are difficult to overcome. There’s also a scene in “Cane River” where Peter visits a bank, and he gets a lesson in how black people’s disenfranchisement is directly proportional to how much property black people own in their communities.

Considering how rare it was for African American independent filmmakers in the 1980s to be able to write, produce and direct their own films with a predominantly black cast, “Cane River” is a time capsule of what types of films could be made under obstacles and barriers in the movie industry—keeping in mind that it was much more expensive in 1980s money to make an independent movie than it is now, because digital technology for independent filmmakers did not exist back then. (The legacy of “Cane River” director Horace B. Jenkins lives on through his son Sacha Jenkins, a journalist and independent filmmaker whose credits include the documentaries “Fresh Dressed” and “Word Is Bond.”)

If people get a chance to see “Cane River,” they might be intrigued to experience some 1980s nostalgia, but they should also appreciate the larger context of how difficult it must have been to make this movie and how long it’s taken for the public to get a chance to see it.

Oscilloscope Laboratories will release “Cane River” in New York City and New Orleans on February 7, 2020. The movie’s U.S. release expands to more cities, as of February 14, 2020.