May 20, 2020

by Carla Hay

Directed by Robin Pelleck and Rebecca Gitlitz

Culture Representation: The documentary “The Story of Soaps” takes a historical look at American TV soap operas and their impact on pop culture, by interviewing a racially diverse (white, African American and Latino) group of actors, screenwriters, TV producers and other people connected to the business of soap operas.

Culture Clash: Many of the people say in the documentary that soap operas are often misunderstood or underrated and that reality TV shows have brought on the decline of soap operas with professional actors.

Culture Audience: “The Story of Soaps” will appeal primarily to people who want to learn more about this type of this “guilty pleasure” TV genre and also take a breezy nostalgia trip for American soap operas’ most notable moments.

The comprehensive and thoroughly entertaining “The Story of Soaps” skillfully manages to make this documentary go beyond the expected compilation of TV clips and commentaries from talking heads about the history of American TV soap operas. The documentary also puts all of this sudsy entertainment into a cultural context that shows how soap operas have had much more influence than they’re typically given credit for when it comes to our entertainment choices and how we see the world.

Directed by Robin Pelleck and Rebecca Gitlitz (who are also executive producers of the documentary), “The Story of Soaps” packs in interviews with numerous people (mostly actors, screenwriters and producers) who are connected to the world of TV soap operas in some way. The long list of actors includes Kristian Alfonso, John Aniston, Alec Baldwin, Maurice Benard, Carol Burnett, Bryan Cranston, Mary Crosby, Eileen Davidson, Vivica A. Fox, Genie Francis, Diedre Hall, Jon Hamm, Drake Hogestyn, Finola Hughes, Susan Lucci, John McCook, Eddie Mills, Denise Richards, Marc Samuel, Melody Thomas Scott, Erika Slezak, John Stamos, Susan Sullivan, Greg Vaughan, Chandra Wilson and Laura Wright.

Screenwriters and producers interviewed in “The Story of Soaps” include Shelly Altman (“General Hospital,” “The Young and the Restless”); Brad Bell (“Husbands”); Lorraine Broderick (“All My Children,” “Days of Our Lives”); James H. Brown (“All My Children,” “The Young and the Restless”); Andy Cohen (“The Real Housewives” franchise); Marc Cherry (“Desperate Housewives”); David Jacobs (“Dallas,” “Knots Landing”); Agnes Nixon (the “All My Children” creator who passed away in 2016); Jonathan Murray (“The Real World”); Ken Olin (“This Is Us”); Jill Farren Phelps (“General Hospital”); Angela Shapiro-Mathes (“All My Children: Daytime’s Greatest Weddings”); Yhane Smith (“Harlem Queen”) and Chris Van Etten (“General Hospital”).

Other people interviewed are People magazine editorial director of entertainment Kate Coyne, “The Survival of Soap Opera” co-author Abigail De Kosnik, “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” co-star Erika Jayne, Netflix consultant Krista Smith, casting director Mark Teschner and Soap Opera Festivals Inc. co-founders Joyce Becker and Allan Sugarman.

Brad Pitt, Julianne Moore, Morgan Freeman and Tommy Lee Jones are named in the documentary as some of the Oscar-winning actors whose early careers on screen included roles in soap operas. Leonardo DiCaprio, Melissa Leo, Marisa Tomei and Kathy Bates are other Oscar-winning actors who were in soap operas before they became famous. Other alumni of daytime soap operas include William H. Macy, Demi Moore and Meg Ryan.

The documentary begins with testimonials from several actors who were in soap operas in the early years of careers, such as Cranston (“Loving”), Baldwin (“The Doctors,” “Knots Landing”), Stamos (“General Hospital”) and Fox (“Days of Our Lives”). Cranston’s first TV job was a guest role in “One Life to Live” in 1968. And when he was in his 20s, he landed a recurring role as Douglas Donavan in “Loving” in 1983.

Cranston says, “I think there are these derisive comments made about soap operas and it’s not fair and it’s not accurate. You’re there to learn. You’re there to bring as much honesty and reality as you can to the moment—and it’s difficult.”

“This genre [soap operas], this job invited me in and put me to work like nobody’s business,” Cranston continues. “It made me feel accomplished, like I broke through a barrier.” Cranston went on to become an Emmy-winning actor several years later, for his role as methamphetamine manufacturer/dealer Walter White in “Breaking Bad,” which he says was a show that was really a soap opera.

Baldwin also says that working in soap operas was extremely valuable to him. He describes “Knots Landing” (where he played the role of Joshua Rush from 1983 to 1985) this way: “It was probably one of the five most important times of my life. They had a very good cast. They had a very talented cast. And that changes everything when you go to work. You don’t care if it’s a soap if you’re working with somebody who’s great. I loved it.”

The grueling hours of working on a soap opera, especially a daytime soap opera that airs five times a week, results in a “sink or swim” atmosphere for a lot of actors who are new to the business. Stamos, who’s best known for starring in the long-running sitcom “Full House,” comments on his 1982-1984 stint as Blackie Parrish in “General Hospital,” which made him a star: “It was great training.”

Fox (who co-starred with Will Smith in the 1996 film “Independence Day”) says of her time on “The Young and the Restless,” where she played the character of Stephanie Simmons from 1994 to 1995: “I learned so much. I learned to hit my cue, how to memorize, how to cry, how to flip my hair.”

“General Hospital” casting director Teschner comments: “There was this stigma to daytime [soap operas] and people misperceiving the acting style as being over-the-top and ‘soapy.’ But I always say that if you can do daytime, you can do any time.” Teschner also mentions that it’s not unusual for a daytime soap opera to film up to 120 pages of dialogue a day, which is the amount of pages that’s typical for a feature-length movie.

“General Hospital” star Francis, who’s been playing Laura on the show since 1977, says in the documentary about her dedication to staying on a soap opera: “Why do I do it? Why do I put myself through this? Because I love to tell stories.”

“General Hospital” co-star Wright, who’s played the role of Carly on the show since 2005, offers a more business-minded perspective to what actors bring to the escapism appeal of soap operas: “It’s our job to sell it to you.” Many of the actors in “The Story of Soaps,” including Melody Thomas Scott (who’s played the character of Nikki on “The Young and the Restless” since 1979), say that because TV brings repeated familiarity in people’s homes, many soap opera fans confuse the actors with the characters that they play on TV.

“The Story of Soaps” has various themed segments which give excellent analysis and commentary on important aspects of soap-opera history. The segment titled “By Women, For Women” details how daytime soap operas have provided many of the best opportunities for women working in television behind the scenes. While male executives dominated prime-time programming, female executives were allowed to shine in daytime television, since the early years of television.

Irna Phillips, who’s often referred to as the “Queen of the Soaps,” could be considered the godmother of daytime TV soap operas, which took the concept of radio soap operas and transferred them to a visual medium. Phillips created the TV soaps “Guiding Light,” “As the World Turns” and “Another World.” She also mentored “All My Children” creator Nixon (who also created “One Life to Live” and “Loving”) and William J. Bell, who created “Another World” (with Phillips), “The Young and the Restless” and “The Bold and the Beautiful.”

In the 1950s, when it was more common for the majority of women to be homemakers, daytime soap operas provided an ideal captive audience for advertisers. The term “soap opera” comes from the fact that during the radio era (before television was invented), soap companies would be frequent advertisers on these drama series.

“The Survival of Soap Opera” co-author De Kosnik notes that when soap operas began on TV, they pioneered the lingering close-ups of actors’ faces to show their emotions, thus adding to the melodramatic appeal. She also mentions that loyalty to certain soap operas would be handed down from generation to generation of women, much like loyalty to certain sports teams would be a generational tradition for men. Although soap operas tend to have a female-majority audience, there’s been a steady increase of male fans of soap operas over the years, especially for primetime soaps.

The documentary’s “Fan-Addicts” segment examines the culture of soap opera fans. Benard (who’s played Sonny Corinthos on “General Hospital” since 1993) calls soap-opera enthusiasts: “The most loyal fans in the world.” The documentary includes a lot of archival footage of fans giving adulation to some of the most famous soap stars over the years, including Stamos and Lucci.

Lucci says of her iconic Erica Kane character, which she played during the entire run of “All My Children” from 1970 to 2011: “I loved playing her. There was such range with her. She was a capable of doing and saying just about anything. And the audience saw humanity in her stories.” And yes, the documentary includes footage of Lucci finally winning her first Daytime Emmy in 1999, after she had a long losing streak of being nominated 18 times and never winning before.

Soap Opera Festivals Inc. co-founder Becker reminisces about the company’s first fan event in 1977, which she says drew “hundreds of thousands of people”—a crowd turnout that probably wouldn’t be possible today, considering how much the popularity of daytime TV soap operas has declined. Becker also describes why soap opera fans are devoted to soap opera cast members: “It’s almost like your own family.”

Legendary comedian Burnett is famously an “All My Children” superfan—so much so that she had a guest-starring role on the show as Verla Grubbs in 1983, 1995, 2005 and 2011. In “The Story of Soaps,” she repeats a story she told in her memoir: When she and her husband spent a month-long vacation in Europe many years ago (before VCRs and the Internet), Burnett asked a friend of hers to send a telegram every Friday with a summary of everything that happened on “All My Children” that week.

One time in the early-morning hours, Burnett was awakened by a hotel employee who was trembling with the telegram, because the visibly shaken employee thought that all the tragic bad news in the telegram was real. Burnett said she started laughing so hard that she began to cry, and the hotel employee thought that she was crying hysterical tears of sorrow, until she explained that what was in the telegram was really an “All My Children” plot summary. Burnett says later in the documentary about “All My Children” being cancelled in 2011: “I’m still angry that they took it off the air.”

A documentary segment called “Love, Lust, Luke & Laura” explores how TV soaps often pushed the boundaries of raunchiness with sex scenes and outrageous love stories, beginning in the 1970s and ramping up even more in the 1980s. Stories about infidelities are very common in soap operas, but the sexual revolution also opened up wilder storylines on soap operas, such as falling in love with a space alien, taboo stepsibling romances and as much nudity as possible.

“General Hospital” characters Luke Spencer (played by Anthony Geary) and Laura were undoubtedly the most famous couple on daytime TV soap operas. Luke and Laura’s 1981 wedding on the show was a major media event, and it remains the highest-rated daytime TV soap opera event, with an estimated 30 million U.S. viewers. However, their relationship was controversial because Luke raped Laura when they first began dating.

De Kosnik says that the 1979 rape storyline was concocted by “General Hospital’s” then-executive producer Gloria Monty (who died in 2006), in a desperate ploy to boost the show’s ratings, because “General Hospital” was on the verge of being cancelled at the time. The show’s producers explained that the rape was “rape seduction” and justified it by saying that Luke really loved Laura. However, that kind of storyline would not have gotten such an easy pass if it had been suggested in later decades.

In “The Story of Soaps,” Francis says about that controversial rape storyline: “I had to justify it for so many years. And I have to say that it feels good to sit here and say it’s awful. They shouldn’t have done it.” In 1998, “General Hospital” made an attempt to remedy this wrong by having Laura angrily confront Luke (they were still married at this point) about the rape.

The documentary segment “It’s a Revolution” is one of the best that demonstrates how soap operas are both a reflection of and influence on culture. Just as soap operas were often the first TV series to have groundbreaking stories about sex, soaps were also among the first scripted TV drama series to address serious social issues. The Vietnam War controversy, abortion, interracial romances, gay teens, transgender relationships, AIDS, mental illness and eating disorders were among the many topics that were considered too taboo for scripted TV series until they were presented on TV soap operas.

“Days of Our Lives” star Diedre Hall, who has played Marlena Evans on the show since 1976, says: “The most compelling thing about daytime drama is that we follow the pulse of what’s goin on.” “General Hospital” writer Van Etten says that he used to be a “deeply closeted” gay man, but he was influenced to come to terms with his own sexuality after seeing Ryan Phillippe portray gay teen Billy Douglas in a 1992 “One Life to Live” storyline.

Emmy-winning “General Hospital” star Benard’s Sonny character is bipolar, and so is Benard in real life. Benard says of the “General Hospital” executives’ decision to make Sonny a biploar character: “I can’t thank them enough.” He says that authentic representation matters in destigmatizing mental illness.

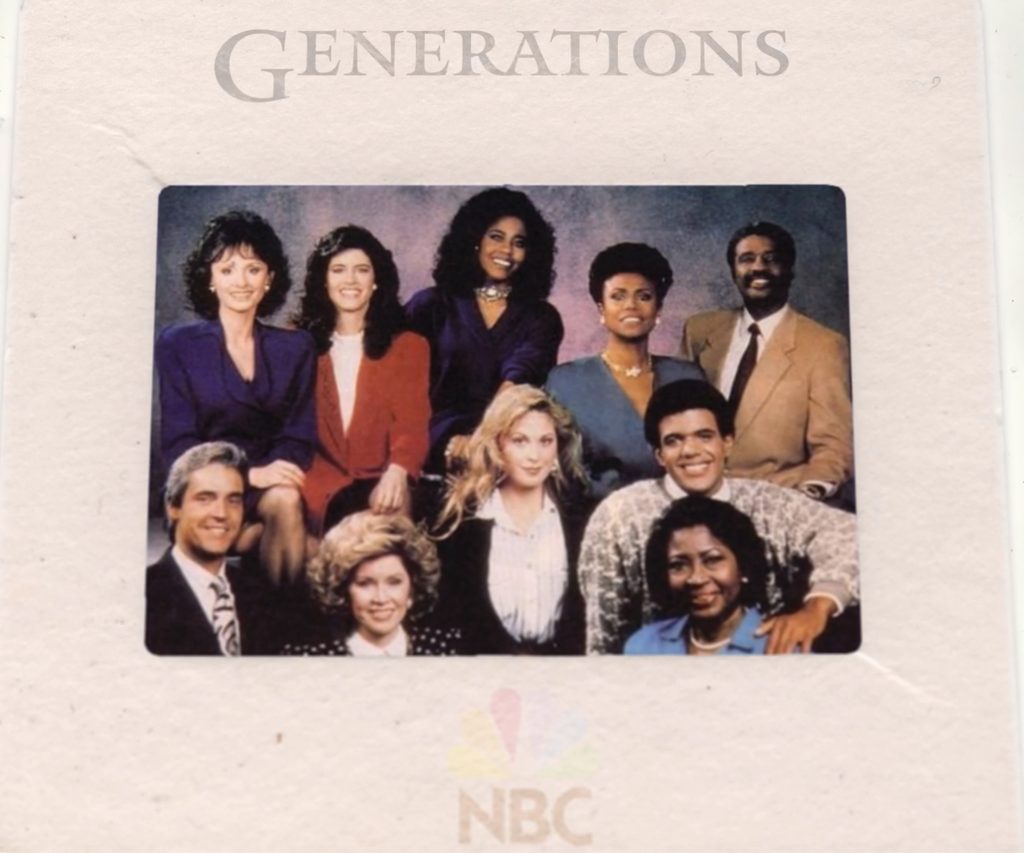

The soap opera “Generations” also led the way in representation for African Americans, since it was one of the first scripted TV dramas to feature a white family and an African American family as equal stars of the show. Although the show didn’t last long (it was on the air from 1989 to 1991), “Generations” co-star Fox comments that the show “changed perceptions” of black people on soap operas, since the black characters on “Generations” weren’t just playing servants, sidekicks or other supporting characters.

But daytime soap operas began to have more competition in popularity with the resurgence of primetime soap operas. The documentary mentions two major social changes that began in the late 1970s and affected the rise of American primetime soaps, such as “Dallas,” “Dynasty,” “Knots Landing” and “Falcon Crest.” First, more women began working outside the home and didn’t have time to watch TV during the day, but they wanted to get their soap-opera fix at night. Second, the VCR became available as a home product, thereby revolutionizing the way people watched TV, by giving people the freedom to record and watch programs whenever they wanted.

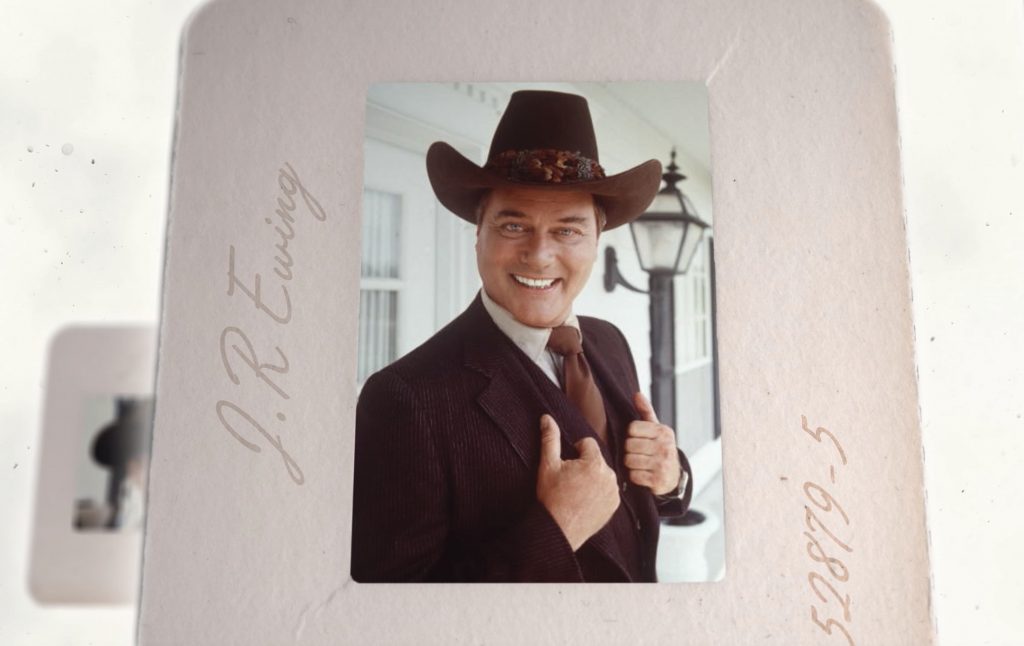

“The Story of Soaps” also points out that the most popular primetime soaps in the 1980s were about rich families because it was a reflection of the decade’s fascination with excess and wealth. Former “Dallas” writer Jacob says it all came down to this concept: “People like to see people that rich [can be] that miserable.” And, of course, the documentary includes a look at the “Who Shot J.R.?” cliffhanger phenomenon of “Dallas” in 1980, when lead character/villain J.R. Ewing got shot in the show’s third-season finale in March of that year, leaving viewers to wonder (until it was revealed in November 1980) who shot him and whether or not he was going to live. An estimated 83 million U.S. viewers watched the fourth-season premiere “Dallas” episode that solved the mystery.

And each popular TV soap opera of a decade is a reflection of what was going on society at the time. “Beverly Hills 90210” and “Melrose Place” were about people from Generation X establishing their identities and careers in the beginning of the Internet age. “Desperate Housewives” was a commentary on middle-aged, middle-class women in the suburbs during the end of the George W. Bush era and the beginning of the Barack Obama era. And awareness in the mid-to-late 2010s of more inclusivity on TV has been reflected in primetime soaps such as “Empire” (a show about an African American family dynasty) and “This Is Us,” which centers on an interracial family with diversity in body sizes.

The documentary’s “Stranger Than Fiction” segment takes an unflinching look at how reality TV has eroded the popularity of traditional soap operas. Reality TV programs have proliferated and thrived because they’re almost always cheaper to produce than scripted shows with professional actors. Several people interviewed say that the O.J. Simpson trial of 1995 was a TV game changer, since live coverage of the trial pre-empted many daytime soap operas, and many TV networks saw that the trial coverage got higher ratings than the soaps. The trial is often called “a real-life soap opera.”

“The Real World” executive producer Murray (who credits the show’s late co-creator Mary-Ellis Bunim for being a TV pioneer for TV soaps) says that they pitched MTV on the concept of “The Real World” as being a “docu-soap.” The late Pedro Zamora, who was on “The Real World: San Francisco” in 1994, is credited with helping bring more awareness to TV viewers about AIDS, since he was the first openly HIV-positive person to be on a reality TV series.

And most reality shows about people’s lives are basically just soap operas with people who usually aren’t professional actors. “The Real Housewives” franchise (which was inspired by “Desperate Housewives”) and the Kardashian/Jenner family are predictably mentioned. Many former reality TV stars have admitted (but not in this documentary) that much of what’s on these reality TV shows is already pre-planned by the show’s producers. Curiously, this documentary didn’t include any footage from “The Bachelor” franchise, which has been described as being among the most “soap opera-ish” reality shows of all time.

The documentary’s “Death of Daytime” segment gives an overview of the cancellations of numerous daytime TV soap operas in the 2000s and 2010s. “Guiding Light,” “As the World Turns,” “Passions,” “All My Children,” “One Life to Live” and “Port Charles” were the long-running American soap operas that were cancelled in these decades. “All My Children” was the cancellation that caused the most viewer outrage, according the documentary. The rise of social media, streaming services, interactive websites, apps and podcasts have further fragmented audiences, who now have millions of more options than the days when there were only a handful of national TV networks in the United States.

Although soap operas seem to be a dying genre, several people interviewed in the documentary point out that many Emmy-winning prestigious shows of the 2000s and 2010s were really soap operas, including “Game of Thrones,” “Breaking Bad,” “The Sopranos” and “Orange Is the New Black.” On the other end of the spectrum, trashy talk shows hosted by the likes of Jerry Springer, Maury Povich, Morton Downey Jr., Sally Jessy Raphael and Jenny Jones also took their cues from soap operas, since these shows thrived on creating nasty fights with guests while the cameras were rolling.

TV news has also absorbed the influence soap operas, as many news programs (especially on cable TV) have taken big stories and presented them as soap operas, with TV hosts and commentators being sort of like a Greek chorus weighing in with their opinions. The overall message of “The Story of Soaps” seems to be that if people have a snobbish attitude toward soap operas, then they should take a look at their favorite entertainment and media and see how much soap operas have had an influence. They might be surprised to see how much soap operas have impacted our culture.

ABC premiered “The Story of Soaps” on May 19, 2020.