March 26, 2023

by Carla Hay

Directed by Chad A. Verdi and Tom DeNucci

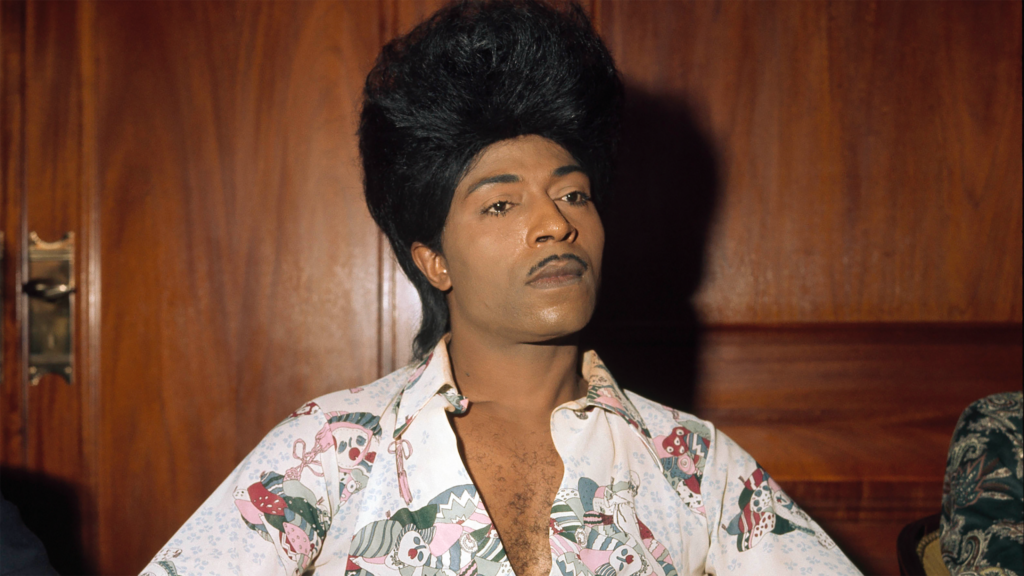

Culture Representation: Taking place in Pennsylvania, Illinois, and California, the documentary film “My Father Muhammad Ali” features a group of African American and white people discussing Muhammad Ali Jr. and the legacy of his father, boxing legend Muhammad Ali.

Culture Clash: Muhammad Ali Jr. struggles with living in the shadow of his father’s fame, while also trying to cash in on that fame and dealing with his own personal problems, such as homelessness and drug addiction.

Culture Audience: “My Father Muhammad Ali” will appeal primarily to people who are fans of Muhammad Ali, but this misleading documentary is really just a self-indulgent pity party for his namesake son.

“My Father Muhammad Ali” is one of the most pathetic “cash grab using a celebrity name” documentaries you could ever see. It’s poorly edited rambling from Muhammad Ali Jr. feeling sorry for himself, because of this troubled son’s personal problems. Don’t expect this “bait and switch” documentary to have any real insight into who boxing legend Muhammad Ali was as a person. (Muhammad Ali Sr. died of Parkinson’s disease in 2016, at the age of 74.) Most of what you’ll see in “My Father Muhammad Ali” is Muhammad Ali Jr. complaining about his life and making pleas and pitches to donate to his sketchy-looking “non-profit foundation” Muhammad Ali Legacy Continues. It’s like watching a really long and shoddily made infomercial.

Directed by Chad A. Verdi and Tom DeNucci (who should be ashamed of themselves for making this sorry excuse for a documentary), “My Father Muhammad Ali” begins with the only real anecdote that Muhammad Ali Jr. (who was born on May 14, 1972) shares about his father in this movie. Muhammad Jr. tells a story that he says took place in August 1984, when he was on a road trip with his father, who was driving the car. Muhammad Jr. says that during this road trip, they were headed to a Travelodge motel. They stopped at a gas station, and his father accidentally left him behind at the gas station.

Muhammad Jr. says that he called Muhammad Sr.’s girlfriend at the time, Yolanda “Lonnie” Williams (who would become Muhammad Sr.’s fourth and last wife, when they married in 1986), to pick him up at the gas station, but she was too busy and couldn’t go. Eventually, someone got in touch with Muhammad Sr., and he came back to the gas station to pick up his son. Muhammad Sr.’s explanation for leaving his son at the gas station was that he forgot that someone else was in the car with him on this road trip. Muhammad Jr. then says in the documentary: “I didn’t realize Parkinson’s disease was setting in at the time.”

“My Father Muhammad Ali” gives a very truncated version of Muhammad Jr.’s dysfunctional life. He describes being named after father as being both a blessing and a curse. He says his parents traveled a lot and were too busy to raise him, so he was mainly raised by his mother’s parents. His mother Khalilah Ali (formerly known as Belinda Boyd) was Muhammad Sr.’s second wife. They were married from 1967 to 1977. Muhammad Jr. says he gets about $1,000 a month from his father’s estate. The movie also acknowledges that Muhammad Jr. has sold his story to tabloids, by showing clips of some of these tabloid articles.

Muhammad Jr. openly admits in this documentary that he’s homeless and struggling with drug addiction, specifically crack cocaine. His family life is also a mess. He had a nasty breakup with his now-ex-wife (who refused to participate in the documentary), and was a deadbeat dad for years to his daughter Saliah Ali, who grew up in foster care and in homeless shelters. In the beginning of the documentary, Muhammad Jr. is hopeful that he will reunite with his wife, whom he married in 2005, but he is soundly rejected when he tries to make this marital reunion happen. He’s also served with divorce papers on camera.

However, Saliah is open to mending her family relationship with him. Saliah is interviewed in the documentary and talks about the emotional pain of having a drug-addicted, absentee father. Muhammad Jr. is remorseful and is shown trying to reconnect with Saliah and attempting to make up for all the lost time that they were estranged from each other.

At one point in the movie, Muhammad Jr. goes back to the property that houses the mansion where the Ali family used to live in California. The current owners of the mansion wouldn’t let the documentary filmmakers inside, so the filming took place outside a front gate on the property. Muhammad then tells some innocuous stories about remembering how his father liked to exercise outdoors on this property.

Anyone who thinks that information is fascinating might be suckered into donating to Muhammad Jr.’s “non-profit foundation,” which he says is for spreading anti-bullying messages and to help teach self-defense boxing to bullied young people. However, the documentary doesn’t actually show any donations to the foundation being used for that purpose. After a while, viewers will wonder if this documentary’s filmmakers ever questioned how legitimate this “non-profit foundation” really is, or if the filmmakers just didn’t care, because they’re using the Muhammad Ali name to try to make money too.

The documentary shows Muhammad Jr. going to Fighter’s Heaven in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania, where Muhammad Sr. famously trained in his youth. Muhammad Jr. constantly drops his father’s name when he meets some fans of his father at Fighter’s Heaven. A Fighter’s Heaven volunteer named Joseph Bassio gushes about the Fighter’s Heaven connection to Muhammad Sr.: “This is kind of like the ground Christ walked on.”

One of the most cringeworthy aspects of the documentary is the domineering presence of Richard Blum, who is often by Muhammad Jr.’s side. Muhammad Jr. describes Blum as his best friend, roommate and business partner. Blum says he’s a retired New York City police officer. At the time this documentary was made, Blum and Muhammad Jr. were living together in the same motel room.

This “partnership” definitely doesn’t look equal, because it’s obvious that Blum has taken the “boss” position for all aspects of a “non-profit foundation” named after Muhammad Ali. Throughout the documentary, Blum coaches/orders Muhammad Jr. on what to say to the media, when it comes to this “non-profit foundation.” Viewers will get the impression that Blum has decided that he will handle all the financial details. Blum doesn’t show any proof that he’s qualified for having this leadership role.

This documentary is so poorly made, the filmmakers never question Blum on why he’s living in a motel with another homeless person and presenting himself as the leader of a questionable “non-profit foundation” as a source of income. Isn’t a retired cop supposed to get a pension, if the cop left the police force in good standing? In the documentary, Blum is vague or evasive about how much money this “non-profit foundation” has actually raised.

And it seems like a lot of people aren’t buying what Blum and Muhammad Jr. are selling. The documentary shows Blum and Muhammad Jr. holding a press conference at Fighter’s Heaven to talk about their “non-profit foundation.” Only one reporter and one photographer show up for this press conference. As usual, Blum tells Muhammad Jr. what to say, or he answers questions for Muhammad Jr.

Other awkward-looking parts of the documentary are the movie’s interviews with Dr. Monica O’Neal, a Harvard-trained clinical psychologist. She’s tasked with giving a psychologist perspective of Muhammad Jr., even though he’s not her patient/client. And later, O’Neal gives a therapy session to Muhammad Jr., who is emotionally guarded and never looks comfortable in this session.

O’Neal has this assessment of the super-close relationship that Muhammad Jr. and Blum have: “It seems like Richard has come into his life and is always trying to support him. He doesn’t really question him. He doesn’t really judge him.” Still, O’Neal has this observation about the relationship: “Something about it feels unclear.”

Family members interviewed in the documentary offer no real insight into Muhammad Sr., and instead give generic answers when talking about Muhammad Jr. and his problems. Rahman Ali, who is Muhammad Sr.’s younger brother, comments that Muhammad Jr. is “Sweet, just like his father.” And when asked to comment on the rough patch in Muhammad Jr.’s life, Rahman curtly says, “It’s none of my business.”

Muhammad Jr.’s mother Khalilah is also evasive in giving details about him and her role in his childhood. She says that her mother, who helped raise Muhammad Jr., didn’t tell her about Muhammad Jr.’s problems that he had as a child. Khalilah will only say this about Muhammad Jr. being raised by her parents: “I probably could’ve helped them with it better.”

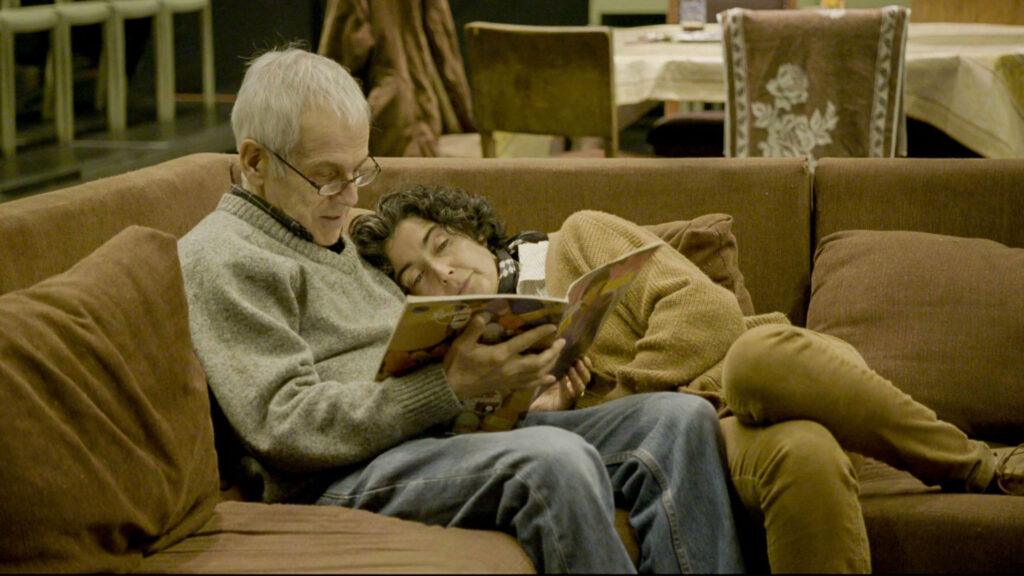

One of the few high points of the documentary are heartfelt comments from Dr. Larry Baran (who was a teacher of Muhammad Jr. at Rosewood-Flossmoor Community High School in Flossmoor, Illinois) and his daughter Heidi Baran Splinter, who was Muhammad Jr.’s schoolmate friend. They share fond memories about Muhammad Jr. becoming like a part of their family. Muhammad Jr. is also shown reuniting with Baran Splinter for a friendly conversation. Dr. Baran was battling cancer when he was interviewed in this documentary, and he passed away in 2020.

“My Father Muhammad Ali” serves no other purpose but to be a public-relations showcase for Muhammad Jr. to rehabilitate his image and beg for money for his “non-profit foundation.” However, the intended purpose sadly backfires, because so much of the movie shows a broken man who is desperately trying to use his father’s name as a way to get money for himself. The documentary filmmakers are part of this exploitation too.

Muhammad Ali Sr. was by no means a perfect person, but he showed the world how to rise to greatness through hard work and self-respect. Unfortunately, this very misguided documentary shows that Muhammad Jr. has not yet learned that lesson. Money handouts aren’t going to make him happy. Hopefully, he’ll get some real help for his problems.

VMI Worldwide released “My Father Muhammad Ali” in select U.S. cinemas, on digital and VOD on January 13, 2023.