December 30, 2022

by Carla Hay

“Is That Black Enough for You?!?”

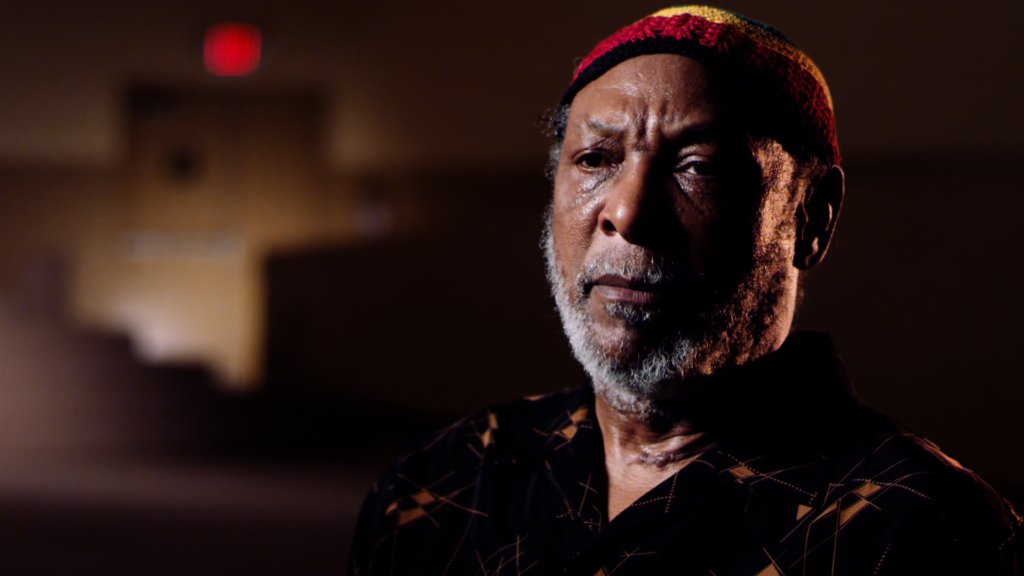

Directed by Elvis Mitchell

Culture Representation: In the documentary film “Is That Black Enough for You?!?,” a predominantly African American group of people (with a few white people), who are all connected to the movie industry in some way, discuss the impact of African American-oriented movies that were made from 1968 to 1978.

Culture Clash: Black filmmakers and cast members had uphill battles dealing with racism and socioeconomic inequalities when making movies centered on African Americans.

Culture Audience: “Is That Black Enough for You?!?” will appeal primarily to people who are interested in cinema history from 1968 to 1978, as well as how sociopolitical issues affected African American movies that were made during this time period.

The title of the documentary “Is That Black Enough for You?!?” is inspired by this catchphrase being said in director Ossie Davis’ 1970 action comedy film “Cotton Comes to Harlem.” It’s a phrase that can apply to the debates and dilemmas about African American representation on screen and behind the scenes, in the art and business of filmmaking. Writer/director Elvis Mitchell gives elegant narration and an informative retrospective in this noteworthy cultural documentary, which puts a deserving spotlight on African American-oriented movies and filmmakers from 1968 to 1978.

“Is That Black Enough for You?!?” (which had its world premiere at the 2022 New York Film Festival) is the feature-film directorial debut of Mitchell, a longtime film critic and historian. As he explains in the documentary, he chose to focus on the years 1968 to 1978 not just because movies from that 10-year time period had a massive impact on him in his youth but also because its the first major renaissance period when movies centered on or starring African-Americans became mainstream hits in the United States and other parts of the world. Through interviews, archival footage and Mitchell’s superb analysis, “Is That Black Enough for You?!?” takes viewers on a journey that is unique, informational and worth watching by anyone who loves movie history.

Mitchell begins the movie on a personal note, by describing how he developed his passion for on-screen entertainment. He says that he and his family would regularly go to the movies when he was growing up. His grandmother, who was originally from Mississippi, was particularly influential on him. She would describe movies as resembling dreams.

From an early age, Mitchell says he was keenly aware of whether or not he was seeing African Americans like himself on screen. He tells an anecdote about how his grandmother wouldn’t let him and other young people in their family watch “The Andy Griffith Show” comedy series, because there were no black people on the show. His grandmother would say about the black people who weren’t part of the American communities represented on screen: “What do you think happened to them?”

As people who are knowledgeable about U.S. history already know, what happened was that it was legal in the U.S. to segregate white people and people of color until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Since movies are often a reflection of what’s going on in society at the time, the origins of African American cinema’s first major renaissance can reasonably be traced back to the effects of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

It just so happens that 1968 was a flashpoint year for African American history that extended to filmmaking. It was the year that civil rights leader Martin Luther King was assassinated, but it was also a year that Sidney Poitier was one of the biggest movie stars in the world and the first black actor to have this type of movie star status. Poitier helped pave the way not just to have international hit movies with a black person as the star but also to create more opportunities for filmmakers who wanted to make movies with a black-majority cast. It was the first time in movie history that movies with black-majority casts would become big hits and/or have an important influence on mainstream culture.

In the late 1960s and through the 1970s, the Black Power Movement thrived and challenged white supremacist racism permeating through all aspects of society. Mitchell comments in the documentary: “Revolt broke out in the movies too.” It wasn’t enough just for African Americans to be on screen, usually in roles showing subservience to white people. There was a movement to have more movies showing the varieties of African American people and communities that exist, including roles where African Americans could be in charge.

Actor/activist Harry Belafonte, a longtime friend of Poitier (who passed away in 2022), says in the documentary that Poitier made a name for himself in the movies by being the only black man among an overwhelming majority of white people. Although Poitier usually played upstanding, professional men, Poitier’s earliest movies were often about him having to assimilate into a white-majority community or society. The tone, whether overt or subtle, was that the characters that Poitier played in these movies had to make white people feel comfortable around him, rather than the character just being allowed to be himself without having to “accommodate” anyone.

Breaking racial barriers can be an achievement that’s diminished if the person breaking the barrier is treated or perceived as a token. Mitchell comments on the type of success that Poitier had with in the first few decades of Poitier’s career: “Unfortunately, he’s the entertainment industry’s reaction to people of color. Black success in the entertainment industry is like finding a $100 bill on the subway: an unrepeatable phenomenon.”

Belafonte says in the documentary that one of the reasons why he stopped making movies from 1959 to 1970 was that these types of Afro-centric movies just weren’t being greenlit by major movie studios at the rate that Belafonte thinks they should have been. And he didn’t want to take the same old racially demeaning roles that were often offered to African American actors at the time. Belafonte comments on how he dealt with racist attitudes in the entertainment industry, “I’m not going to do anything that I didn’t think was worthy of being done. I have a destination that answers your denial of what I could be.”

Fortunately, many African American filmmakers didn’t want to wait around for major studios to offer them opportunities. “Is That Black Enough for You?!?” gives an excellent overview of the African American independent filmmaking community that grew from the late 1960s onward. Many of these filmmakers hired large numbers of black people in front of and behind the camera.

Among the African American filmmakers who get props in the documentary for being directors who hired a lot of black people from 1969 to 1978 are Charles Burnett (one of the people interviewed in the film), William Greaves, Melvin Van Peebles, Stan Lathan (also interviewed in the documentary), Max Julian, Davis and Poitier. Julian is mentioned as one of the few African American filmmakers at the time who owned his movies. The documentary also gives credit to pre-1960s filmmakers who paved with way with African American-majority casts, including Oscar Micheaux and Alice Guy-Blaché.

Poitier made his feature-film directorial debut with the 1972 Western “Buck and the Preacher,” in which he co-starred with Belafonte. In the documentary, Belafonte says he believes that the movie was not a commercial success because mainstream movie audiences at the time just weren’t ready to see a movie centered on black cowboys. To be fair, Belafonte notes that black audiences didn’t really show up for the movie either. He comments that the movie’s adversaries were “black perception of itself and black perception as the world sees us.”

The documentary mentions the 1968 Western “Once Upon a Time in the West” (directed by Sergio Leone) as one of the few mainstream films of this era that actually had a black person in a significant speaking role: the character of Stony, played by Woody Strode. Although some might think of Stony as a black token, this representation mattered to a lot of people. As an example, it’s mentioned in the documentary that Isaac Hayes (who won an Oscar for composing the music to 1971’s “Shaft”) was influenced by Stony when writing film music.

“Is That Black Enough for You?!?” cites director George Romero’s 1968 horror classic “Night of the Living Dead” as the first hit movie to have a black man (Duane Jones, in the character of Ben) starring in an action hero role. Mitchell says in the narration that what was also groundbreaking about the film was that Ben’s race wasn’t the focal point of “The Night of the Living Dead,” because the movie was about people surviving a zombie invasion. Mitchell notes that “Night of the Living Dead” was embraced by a lot of African American militants at the time because of the parallels between what happened in the movie and what was going on with all the civil unrest in America.

Numerous other seminal feature films starring African Americans are mentioned in “Is That Black Enough for You?!?,” including 1969’s “Putney Swope” (directed by Robert Downey Sr.); 1971’s “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (directed by Melvin Van Peebles); 1972’s “Super Fly”; 1972’s “Lady Sings the Blues” (directed by Sidney J. Furie); 1972’s “Sounder” (directed by Marvin Ritt); and 1974’s “Claudine” (directed by Jack Starrett). Impactful documentaries during this era included the 1970 Muhammad Ali biography “A.K.A. Cassius Clay” (directed by Jimmy Jacobs) and the 1973 concert film “Save the Children” (directed by Lathan).

“Is That Black Enough for You?!?” also celebrates some of the breakthrough African Americans who were Oscar nominees from 1968 to 1978, including Rupert Crosse (Best Supporting Actor nominee for 1969’s “The Reivers”), James Earl Jones (Best Actor nominee for 1970’s “The Great White Hope”), Diana Ross (Best Actress nominee for “Lady Sings the Blues”), Cicely Tyson (Best Actress nominee for “Sounder”), Paul Winfield (Best Actor nominee for “Sounder”) and Diahann Carroll (Best Actress nominee for “Claudine”). One of the people interviewed in the documentary is Suzanne de Passe, who became the first black woman to get a screenplay Oscar nomination (Best Original Screenplay), for co-writing “Lady Sings the Blues.”

Other people interviewed in the film include entertainers Samuel L. Jackson, Whoopi Goldberg, Laurence Fishburne, Glynn Turman, Zendaya, Billy Dee Williams, Sheila Frazier, Mario Van Peebles (son of Melvin Van Peebles), Margaret Avery, Roscoe Orman and Antonio Fargas. Louise Archambault Greaves (William Greaves’ widow) and “Super Fly” cinematographer James Signorelli also weigh in with their thoughts. Williams comments on his sex-symbol status that he had, beginning in the 1970s: “It was very funny to me. It was something that had never happened to me before.”

Frazier tells a memorable story about how she was initially rejected for the leading actress role in “Super Fly.” She was so hurt by this rejection that she changed her phone number, only to find out a few months later by randomly meeting one of the filmmakers that they had been trying to contact her during those months because they changed their mind. Fishburne talks about how he was originally cast in “Claudine,” but when Diane Sands (who originally was cast in the title role) died in 1973 of leiomyosarcoma (a rare form of muscle cancer), the filmmakers decided to make major recastings for the film.

Mario Van Peebles tells some great behind-the-scenes stories about his father Melvin, who pioneered the marketing tactic of releasing a movie’s soundtrack before the movie. (“Super Fly” used the same tactic to great success.) Mario Van Peebles says that his father used to have a secretary named Priscilla, who wanted to be an actress in “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song,” but her boyfriend at the time (a member of Earth, Wind & Fire who is not named in the documentary) wouldn’t let her. However, as a compromise, Melvin convinced Earth, Wind & Fire to write the soundtrack music for the movie.

Mario Van Peebles also tells a story about how his father came up with a clever idea to convince nervous white studio executives to distribute the potentially controversial 1970 comedy film “Watermelon Man.” The movie was about a racist white man (played by African American actor Godfrey Cambridge), who woke up one morning to find out that he had turned into a black man. Mario says that before the meeting with the studio executives, his father payed an African American sanitation worker in the building to be in the screening room and laugh at the jokes in the movie while the executives watched “Watermelon Man.” This “one-man focus group” tactic worked, says Mario Van Peebles, who describes this tactic as being “like racial jiu jitsu.”

The “blaxploitation” films of the 1970s (include those made by actor/producer Rudy Ray Moore) have their share of fans and critics. As mentioned in the documentary, the upside to the “blaxploitation” genre of this era is that they were the first major hit films to have African American women as the central action stars, not just as sidekicks or supporting players. Pam Grier and Tamara Dobson are credited with being pioneers for African American female action stars, with Grier’s 1973 film “Coffy” and Dobson’s 1973 film “Cleopatra Jones” mentioned as their most influential movies. The documentary also mentions some of the low points in blaxploitation films, including “Mandingo” and “Coonskin,” both released in 1975.

This era of African American-oriented filmmaking also gave rise to a new wave of African American movie stars who came from backgrounds other than acting. Ross was famous for being in the Supremes and had a successful solo singing career when she landed her first movie star role in “Lady Sings the Blues.” Richard Pryor was a well-known stand-up comedian before he had his movie breakthrough in “Lady Sings the Blues.” Jim Brown was a football star before he launched his movie career, which included action films such as 1968’s “Kenner” and 1972’s “Black Gunn.”

One of the best things about “Is That Black Enough for You?!?” (which has great editing by Michael Engelken and Doyle Esch) is that this documentary doesn’t just spotlight mainstream hits but it also gives screen time to underrated movie gems that prominently feature African Americans. Greaves’ 1968 “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One” is mentioned as an important experimental film from an African American filmmaker. The 1972 drama “Black Girl” (directed by Davis) is described as an often-overlooked African American movie that’s worth watching.

The 1976 musical drama “Sparkle” (directed by Sam O’Steen) is cited as an influential precursor to the “Dreamgirls” stage musical and movie. The 1975 urban drama “Cornbread, Earl and Me” (directed by Joseph Manduke) was influential to 1991’s “Boyz N the Hood,” says “Boyz N the Hood” co-star Fishburne. And before black superheroes got their own movies with 1997’s “Spawn,” 1998’s “Blade” or 2018’s “Black Panther,” there was 1977’s “Abar, the First Black Superman,” directed by Frank Packard.

The commercial disappointment of the 1978 movie musical “The Wiz” is mentioned as the end of an era, because movie executives began to think that African American-oriented movies were starting to become less popular with the moviegoing public. It then became harder for African American-oriented movies to get financing until a new renaissance emerged in the 1990s, with hit films such as “Boyz N the Hood,” “House Party,” “Menace II Society,” “Friday,” “Set It Off,” “The Best Man” and “Soul Food.” If Mitchell or any other filmmakers want to do a documentary about the 1990s renaissance of African American movies, there would be plenty of people who would be interested.

“Is That Black Enough for You?!?” is more than a love letter to the movies of 1968 to 1978 that celebrated African Americans. It’s also a full immersion into a fascinating culture with a narrative that is very thoughtful and almost poetic. (For example, Mitchell has this to say about some of the music of the movies featured in the documentary: “The scores weren’t just textures, but detonation of thought and sound.”) It’s a documentary that gives people a better appreciation for these movies, as well as inspiration and anticipation for any more creativity to come in African American-oriented filmmaking.

Netflix released “Is That Black Enough for You?!?” in select U.S. cinemas on October 28, 2022. The movie premiered on Netflix on November 11, 2022.