American Place Theatre, Billy Lyons, documentaries, film festivals, It Takes a Lunatic, movies, Netflix, New York City, plays, reviews, Tribeca Film Festival, TV, Wynn Handman

May 4, 2019

by Carla Hay

Directed by Billy Lyons

World premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City on May 3, 2019.

Wynn Handman might not be a household name, but as an acting teacher and as a co-founder/artistic director of the American Place Theatre in New York City, he’s had an enormous influence on numerous actors who are world-famous and/or highly respected. This talky documentary takes an in-depth, sometimes overly fawning look at Handman’s accomplishments. Even though there’s an impressive array of famous actors who share the experiences they’ve had with Handman, be prepared to sit through a documentary where there’s plenty of interviews and archival photos but unfortunately not enough archival film footage to make it a more vibrant movie.

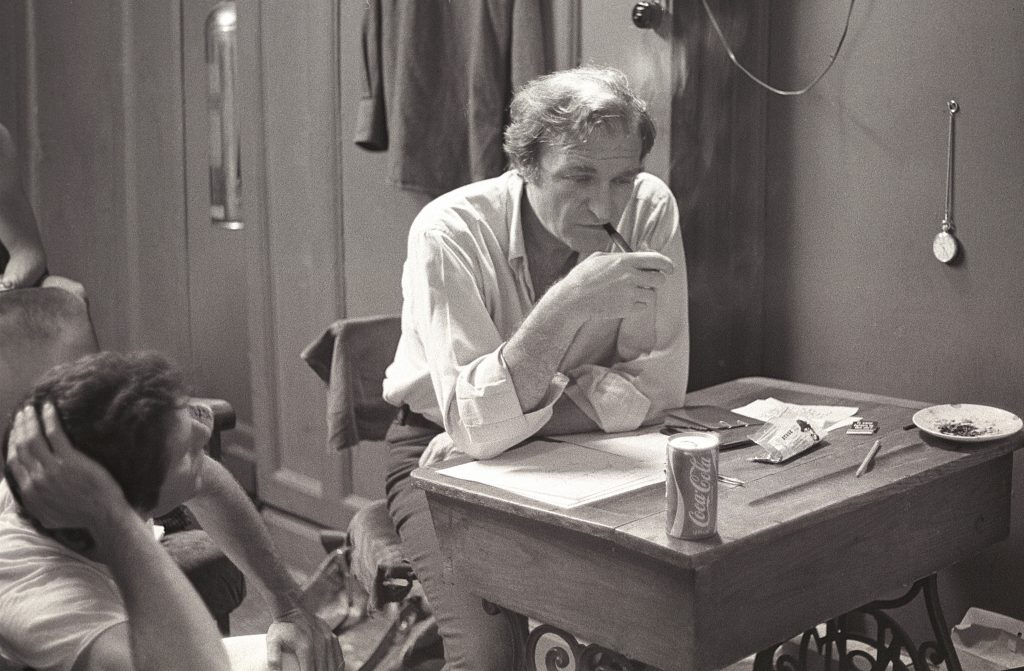

Handman, who was born in 1922, is also interviewed in “It Takes a Lunatic.” He describes his childhood growing up in Manhattan’s Inwood neighborhood as happy. He wanted to be in the Navy, but enrolled in the Coast Guard instead. As a mentor/leader in the profession of acting, Handman is described as both “rough and tumble” and “intellectual” by past colleagues. The movie describes Handman has having two lives and two legacies: first as an acting teacher and later as artistic director of the off-Broadway American Place Theatre.

The celebrities who give testimonials about Handman as an acting coach or American Place Theatre artistic director include Richard Gere, Alec Baldwin, Susan Lucci, Michael Douglas, James Caan, Chris Cooper, Marianne Leone Cooper, Andre Bishop, Connie Britton, Lauren Graham, John Leguizamo and Aasif Mandiv. Lucci says that as an acting coach, Handman was “so encouraging, never destructive.” Baldwin adds that Handman “never gave someone a critique they couldn’t handle.”

After years as a successful acting teacher, Handman took a big career risk by co-founding the American Place Theatre in 1963, with Sidney Lanier and Michael Tolan, at the location that formerly housed St. Clement’s Church in midtown Manhattan. Handman was told that “it would take a lunatic” to operate this unusual theater, because it was a non-profit company, and its business model was to make money from customer subscriptions, not from individual ticket sales. This uncommon approach to operating a theater allowed Handman and the other theater decision makers to take more artistic risks in the theater’s productions, since the sales were already pre-paid through subscriptions.

The American Place’s first full production in 1964 was “The Old Glory,” a trilogy of one-acts by poet Robert Lowell and starring Frank Langella. “The Old Glory” ended up winning five Obie Awards, including Best American Play and Best Actor for Langella. Another notable production in the American Place’s early years was 1967’s “La Turista,” a two-act play by Sam Shepard and starring Sam Waterston and Joyce Aaron. (The documentary includes an interview with Shepard, who died in 2017.)

But the American Place was also known for controversy. Ronald Ribman’s 1965 play “Harry, Noon and Night,” starring Dustin Hoffman as a transvestite Nazi, was controversial, mostly because the play had a live decapitation of a chicken. After those live beheadings sparked a lot of public outrage, the play switched to using fake chickens. “The Cannibals,” George Tabori’s 1974 play about the Holocaust, was one of the American Place’s most divisive productions. The documentary points out that the play was more controversial in the United States than it was in Germany. In the documentary, Handman remembers getting a lot of hate mail every time the American Place was embroiled in controversy.

The words “true,” “truth” and “truthful” are used a lot in the documentary to describe Handman and the people he inspired. Eric Bogosian, whose third one-man play “Drinking in America” was produced by the American Place, says of Handman: “He’s not a lunatic. He’s a true believer.”

Even with interviews and testimonials that talk about all the brilliant work that Handman can take a lot of credit for influencing, there simply isn’t enough filmed footage of a lot of these stage productions. Plays, rehearsals and acting classes in Handman’s heyday were usually not filmed for posterity, so it’s not director Billy Lyons’ fault that still photos are the main visuals he has to work with to show what people are discussing in the documentary. (And thankfully, Lyons chose not to film re-enactments for “It Takes a Lunatic,” which is his first feature film.) Perhaps “It Takes a Lunatic” would have been better-suited as a podcast instead of a movie.

The lack of archival film footage isn’t the documentary’s main shortcoming. By putting Handman on such a high pedestal, the documentary feels like it was made by a star-struck fan instead of a more objective filmmaker. For example, the controversy that Handman created with some of American Place’s productions is acknowledged in the film, but the movie doesn’t interview any of Handman’s critics, rivals or people he inevitably alienated in his career. The constant praise of Handman is repetitive and the movie’s slow pace makes the documentary duller than it needs to be. “It Takes a Lunatic” should be commended for gathering so many well-respected actors to share their admiration of Handman, but the documentary probably won’t be very appealling to people who have no interest in acting or theater productions.

UPDTAE: Netflix will premiere “It Takes a Lunatic” on October 25, 2019.