September 4, 2020

by Carla Hay

“I’m Thinking of Ending Things”

Directed by Charlie Kaufman

Culture Representation: Taking place in unnamed parts of the U.S., the drama “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” has an all-white cast representing the middle-class.

Culture Clash: A man and a woman, who have been dating each other for six weeks, go on a road trip to meet his parents, but the trip turns out to be more than meets the eye, as they experience arguments, family conflicts and secrets from the past.

Culture Audience: “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” will appeal primarily to people who are fans of writer/director Charlie Kaufman’s unconventional style of filmmaking.

People who aren’t familiar with the work of writer/director Charlie Kaufman won’t be fully prepared for the eccentric head trip that is his dramatic film “I’m Thinking of Ending Things.” Kaufman won an Oscar for co-writing the original screenplay for 2004’s “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” (which is probably his most famous movie), and he wrote the Oscar-nominated screenplays for 1999’s “Being John Malkovich” and 2002’s “Adaptation.” He also wrote and directed the 2014 animated film “Anomalisa” and 2008’s “Synecdoche, New York.” What all of these movies have in common is that they defy convention and are often about characters that spend a lot of time inside their heads. People who hate Kaufman’s movies usually think the movies are too weird.

Therefore, anyone who watches “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” (which Kaufman adapted from Iain Reid’s novel of the same name) should know in advance that it won’t be a story told in a straightforward way, and people are doing to say and do things in a bizarre manner. The movie starts out by giving the impression that it’s going to be told from the perspective of one character, but then it ends up being the story of another character. In other words, “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” can only be recommended to people who are up for a ride that isn’t really supposed to be logical but it’s more about conveying atmosphere, capturing moods and presenting themes in an often-abstract way.

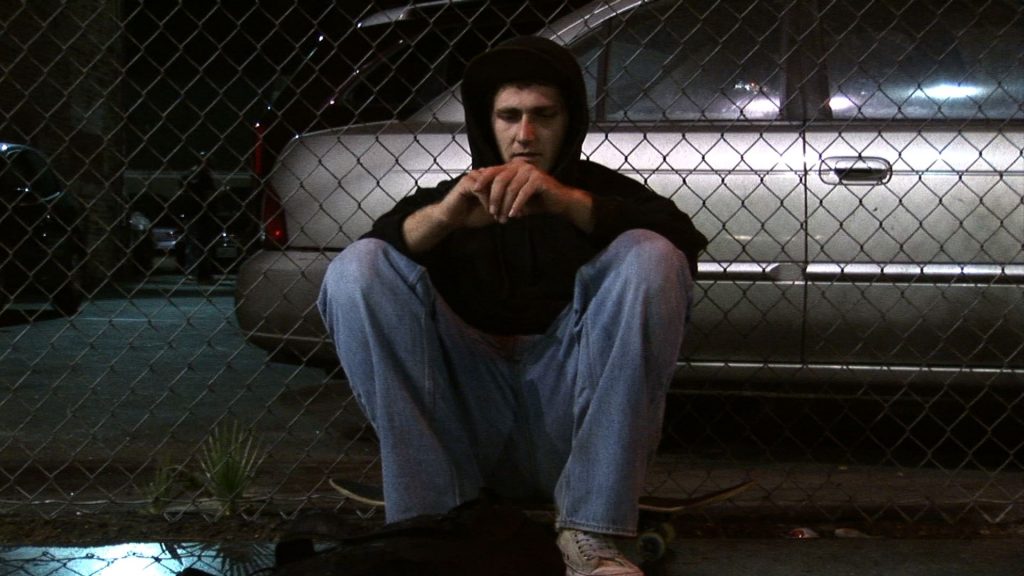

The foundation of the story is a road trip during heavy snowfall that could turn into a storm. Jake (played by Jesse Plemons) and his girlfriend (played by Jessie Buckley) are an American couple who are both in their late 20s. Jake is driving them to his parents’ farmhouse, where his girlfriend will be meeting his parents for the first time. Jake and his girlfriend have been dating each other for about six weeks. They plan to have dinner with Jake’s parents before leaving to go back on the road that night, since his girlfriend has to get up early the next morning for work.

The girlfriend doesn’t officially have a name in the story, but throughout the movie, she is called different names that start with the letter “L” (such as Louisa, Lucia and Lucy), which is bound to confuse people watching this film. And, at different times in the movie, she is described as having different professions, such as artist painter, gerontology student or waitress. The parents don’t have names either, but Jake’s mother (played by Toni Collette) is American, while Jake’s father (played by David Thewlis) is British. The movie also doesn’t mention where in the United States this story takes place.

Before, during and after this dinner, Jake’s girlfriend contemplates the pros and cons of staying in this relationship with Jake. Her inner thoughts are heard in voiceover narration. And throughout the movie, she keeps repeating “I’m thinking of ending things,” every time she mulls over whether it’s better to break up with Jake before the relationship turns bad or if it’s worth sticking with him to see if things will improve between them. As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that Jake is more infatuated with his girlfriend than she is with him.

She’s already starting to doubt that they’re compatible, and she figures that meeting his parents will give her a better idea what kind of family she’ll have to deal with if her relationship with Jake becomes more serious. She says in one of her inner thoughts, “Jake’s not going anywhere. People tend to stay in relationships past their expiration date.”

While driving to the farmhouse, the girlfriend thinks, “I should be more excited, but I’m not.” On the other hand, she admits to herself why she would want to stay in this relationship with Jake: “It feels like I’ve known Jake longer than I have … We have a very real connection.”

During the ride, Jake and his girlfriend talk mostly about music and poetry. She is surprised to find out that Jake is a big fan of musical theater, and “Oklahoma!” is his favorite musical. (There are several references to the “Oklahoma!” musical in this movie.) Jake also mentions poet William Wordsworth and his “Lucy” poems. When his girlfriend recites a poem that she wrote, Jake assumes he was the inspiration for that poem, and she’s annoyed by the assumption. Jake comments, “That’s why I like road trips. It’s good to remind you that the world is bigger than outside your head.”

Jake seems nervous about his girlfriend meeting his parents. When Jake and his girlfriend arrive at their destination, he insists on giving her a short tour of the property before heading into the main house. They go to a barn, where a few sheep have frozen to death. The girlfriend is slightly horrified, but Jake nonchalantly says that the sheep’s bodies are too frozen to move and the bodies will be moved when the bodies become naturally thawed out. Jake also mentioned that the pig sty in the barn was where a pig was found being eaten alive by maggots. Life can be cruel on a farm, Jake says.

Inside the house, Jake’s parents don’t appear right away. Jake’s girlfriend looks uncomfortable until she sees the family’s friendly Border Collie, because she likes dogs. She also notices that the basement door has dark scratch marks all the way up to the top of the door. When she asks Jake what caused those scratches, he says it was the dog, but that answer isn’t believable at all, because the dog wouldn’t be able to reach that high. Jake also says, “I hate the basement.” The secret of the basement is revealed in bits and pieces during the rest of the movie.

And viewers soon see why Jake was so nervous about his girlfriend meeting his parents. When Jake’s parents finally appear, they start out as very friendly and effusive to his girlfriend. But as they sit down for dinner, his parents say inappropriate things and at times act mentally unbalanced. His mother cackles and snorts loudly at the wrong moments and at her own jokes that only she thinks are funny. Jake’s father is overly critical and thinks he is always correct.

For example, Jake’s girlfriend mentions that she is an artist who likes to paint landscape portraits. She shows Jake’s parents some photos of her paintings that are on her phone. When she mentions that she hopes to convey certain emotions with these paintings, Jake’s father vehemently disagrees and tells her that the only way emotions can be expressed in a painting is by having a human being in the painting. Jake’s girlfriend shares her opposite point of view, but out of politeness she chooses not to get into an argument with Jake’s father about it.

Meanwhile, Jake’s parents are very argumentative with each other. Jake tries to hold back and not get involved in taking sides, but at one point he snaps and tells his parents to stop being so obnoxious. The more time that Jake’s girlfriend spends at the family home, the more she sees that Jake has had long-simmering tensions with his parents that seem to go all the way back to Jake’s childhood.

One of the recurring themes of the movie is that Jake’s girlfriend is anxious to go back home, but Jake keeps thinking of reasons to delay this return trip. Meanwhile, the snowfall outside is getting worse and Jake’s girlfriend doesn’t want to be stuck in a snowstorm. Jake and his girlfriend get into arguments that start to escalate.

While some of this relationship drama is going on, the movie cuts back and forth between scenes of an elderly janitor (played by Guy Boyd), who works at a high school. (The janitor’s relevance to the rest of the story is explained later, but not in a straightforward manner.) There are also various choreographed dance scenes from “Oklahoma!” and other musical numbers at the high school and elsewhere. Jake breaks out into song at one point in the movie. And there are scenes involving diners and waitresses that won’t make much sense until toward the end of the film.

In one of these scenes, the janitor watches a movie on a TV monitor at the high school where he works. The movie he’s watching is of a man surprising his waitress girlfriend at the diner with an elaborate show of adoration, but it’s disruptive to the customers, and she ends up getting fired. The movie that the janitor is watching then cuts to the end credits to show that it was directed by Robert Zemeckis. It’s an example of the type of quirky comedic touches in the story that are best appreciated by movie aficionados who might get some inside jokes.

Even if people find this movie’s storyline hard to take, “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” is still compelling to watch for the performances by the main actors in the cast. Collette is wonderfully unhinged as Jake’s mother, while Buckley gives some impressive monologues during the movie. Plemons’ Jake character is the most complex because it’s hinted at throughout the story that he has some secrets hidden underneath his mild-mannered exterior. Thewlis plays a self-righteous and arrogant character as Jake’s father, but he’s never boring to watch.

At 134 minutes, “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” is a little too long and could have used some fine-tuning in its editing. The movie is actually written and structured more like a play than a traditional narrative film. But it’s the kind of movie that, if people like it enough, it’s probably better experienced after a repeat watching, to pick up on things that might have been missed on the first viewing. However, “I’m a Thinking of Ending Things” is a perfect example of why Kaufman’s filmmaking is definitely an acquired taste and not everyone will want to go back for a second helping.

Netflix premiered “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” on September 4, 2020.